Our last installment examined the evidence for frescoes that Pietro Gagliardi (1809-1890) executed in one of the 19th century wings of the Villa Aurora. The first clue that caught the eye of Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi director Corey Brennan? A grainy photograph that ran in several American newspapers in the winter of 1904.

The image (see above) showed part of an art and architectural drawing exhibition staged by the young American Academy in Rome. (The institution was renting the Villa Aurora from the Boncompagni Ludovisi at the time.) The newspapers showed the Academy Fellows’ work set in a richly frescoed sala—with ceiling paintings that since have disappeared from view in the Villa Aurora.

The theme of the frescoes? Scenes from the life of Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni (1506-1572-1585), specifically his reform of the calendar in 1582, and reception of the first Japanese embassy to the West in 1585.

Gagliardi’s fresco depicting Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni’s calendar reform of 1582. The legend (in Latin): “The memorable reform of the Roman calendar, attempted by many, was brought to completion by Gregory XIII. AD 1582.”. Photo (1904): Collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

A reference from Gaetano Moroni‘s Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica (1860) fills out the rest of the basic story. Antonio Boncompagni Ludovisi (1808-1883), Prince of Piombino (VII) from 1841, commissioned Gagliardi to paint the frescoes. One Antonio Urtis colloborated with designs in stucco. The date for their work was the years 1855-1858. But what is missing from Moroni’s impressively precise description is the exact context in the Villa Aurora—other than the general indication that it was among “tante belle sale” in the “nuovo tratto d’edifizio” that architect Nicola Carnevali designed for the Prince.

Gagliardi’s fresco commemorating the Japanese embassy of 1585 that met with Gregory XIII in the Sala Regia of the Apostolic Palace. Legend (in Latin): “In a solemn assembly of Cardinals, Gregory XIII kindly welcomes the envoys of Japanese kings, AD 1585.” Photo (1904): Collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

However Brennan, working closely with Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi (who very generously provided photographs of all the ceilings in the Villa), found a telling reference in a well-known published source. Charles Moore in his (1929) Life and Times of Charles F. McKim devotes a number of pages to events culminating in the January 1904 exhibition of American Academy Fellows’ work, held in five different rooms of the institution’s rented home in the Villa Aurora. Moore uses as his primary source an eyewitness description by Helen Amelia (Millard) Mowbray (died 1910), first wife of H. Siddons Mowbray (1858-1928). a highly accomplished figure and mural painter who was then the Academy’s Director.

Here are the most relevant excerpts from Helen A. Mowbray’s diary, as quoted by Charles Moore, with emphases ours.

“1903. October 6. Villa dell’ Aurora. We left the detestable apartment of the Countess di Brazza [= the American-born Contessa Cora Slocomb Savorgnan di Brazzà, 1887-1944] on October 4, and here we are living. It is a most charming place, the garden is lovely and no place could be more livable than the house, so pleasantly and agreeably arranged. With our own six chairs and some rented furniture we have made ourselves very comfortable, but of course so elegant a place needs plenty of furnishings, particularly in the way of hangings, rugs, etc. The villa was the casino of the Palazzo Ludovisi; it is called the Aurora on account of a painting in the entrance hall by Guercino (very bad). There are also decorations in the large salon, commemorating the making of the Gregorian calendar.”

“1904. January 14. The opening of the Academy took place on the 11th…The Queen [Elena of Savoia, 1873-1952] came in first and seemed surprisingly tall and a beautiful woman, with a particularly lovely expression. She was closely followed by the King [Victor Emmanuel III, 1869-1947]. He is small, and short in the legs; his head and face are fine; he is decidedly blond. He wore a long cape over his uniform. His whole bearing was dignified and kingly, in spite of his size, which they say he feels keenly….Mr. Meyer [i.e., George von Lengerke Meyer, US Ambassador to Italy, 1900-1905] had several times remarked that the narrow spiral staircase [of the Villa Aurora] would be difficult for the King’s weak legs, and I could see that it was. H. accompanied the King and Queen with Mr. Meyer through the different rooms.”

“For the dinner the same night the table was laid in the large sala of the villa, where the mural decorations commemorate events in the life of Gregory XIII. There were twenty-five plates. Mr. Meyer sat opposite H. [Siddons Mowbray]….For three days the exhibition was the thing to go to in Rome. The Italians were delightfully kind and most courteous. I wish I could say as much for the Americans living in Rome.”

We have seen that Gaetano Moroni locates the Gagliardi paintings celebrating the achievements of Gregory XIII in the Villa Aurora’s mid-19th century addition. And Mrs. Mowbray’s diary explicitly states that the frescoes in question are in the Villa’s “large salon” or “large sala“. By process of elimination, that most immediately leads one to a spacious room in the southeast wing of the Villa Aurora that still today is devoted primarily to dining. As it so happens, the dimensions of that salone seem to correspond closely to the mystery room in the Villa Aurora, as seen in the 1904 newspaper photo that prompted this investigation.

Above three photos: an attempt to “morph” the 1904 newspaper photo of the American Academy show with the present-day Salone of the Villa Aurora. The door on left, partly visible in the 1904 photo, correlates exactly with an existing entrance to the room. The door visible in the 2012 photo (near center of image) opens onto a shallow closet, original to the room. Brennan: “The American Academy Fellows may have covered the walls with fabric for their show, and so hiding that door.” Credit for contemporary photo: collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

There’s one major snag. That dining room in the Villa Aurora, which is in the shape of a pavilion vault closely corresponding to the sala in the newspaper photo, of course boasts its own elaborate decorative scheme, apparently dating to the mid-19th century. The vault consists of a series of high reliefs in stucco, surrounding two large oval and two smaller round paintings in fresco.

The paintings have been described as landscape “genre scenes”. But each of the two oval compositions admits of a precise identification. The first, on the eastern wall of the Dining Room, is a depiction of the 16th century Mihrimah Sultan Mosque, designed by the famed Ottoman architect Sinan hard by the quay of the Üsküdar section of Istanbul. That is on the Asiatic side, in a part of Istanbul closest to Mecca. There are more than 170 mosques in that part of the city.

Image above: detail of one of two oval frescoes in “Sala dell’ Ottocento”of the Villa Aurora. Below: Thomas Allom (1804-1872), The Mihrimah Sultan Mosque at Uskudar, on Anatolian Shore of Bosphorus, Facing Istanbul (1838). Allom’s painting captures essentially the same scene, from the same vantage point

The second of the two oval paintings in the Villa Aurora’s Dining Room, on the western wall, depicts a festive scene in a park. Musicians in Ottoman-era dress perform on instruments while women dance alongside a river or canal; the tower of a minaret again suggests a Turkish context.

On the western wall of the Villa Aurora’s Dining Room as it stands today, a depiction of an Ottoman-era dancing scene

The vault of the Dining Room is further punctuated by variegated marble insets. At the corners of the vault, pairs of winged putti rest on shells adorned with feathers and other decorative elements. At the center of the ceiling, two winged cherubs hold the arms of the Boncompagni Ludovisi family.

Indeed, this room in the Villa Aurora has earned the designation “Salone dell’Ottocento”. And the artist? The work is attributed to none other than Pietro Gagliardi, working with Antonio Urtis.

After a bit of sleuthing, Corey Brennan discovered what seems almost certainly to be the direct source for the two oval paintings. It is a well-known travel book first published in London and Paris in 1838, but that saw many subsequent editions: Constantinople and the Scenery at the Seven Churches of Asia Minor, illustrated in a series of Drawings from Nature by T[homas]Allom with an historical account of Constantinople and description of the plates by the Rev. R[obert] Walsh. The depiction and description of the mosque are found in vol. II p. 6 of that work; and precisely the same dancing scene is presented in Vol. I facing p. 57.

Thomas Allom’s illustrations for Constantinople and the Scenery at the Seven Churches of Asia Minor (1838), which appear to be the direct source for the two oval frescoes in the Dining Room of today’s Villa Aurora. Image above: “Mosque of Buyuk Djami, Scutari, Asia Minor” [=Mihrimah Sultan Mosque, Üsküdar, Istanbul]. Image below: “The Babyses, Or Sweet Waters of Europe”. It pictures Greek women dancing to Ottoman musicians during St. George’s Day celebrations (5 May, according to the Gregorian calendar). The location pictured is at the top of the inlet of the Golden Horn, near what is now the suburb of Eyüp

Obviously there is a problem here, and perhaps it’s easiest to let Corey Brennan try to explain. “I can’t claim to know precisely what’s going on here”, Brennan admits. “But taking everything into consideration, it seems reasonable to suppose that the Gagliardi Gregory XIII frescoes—if they were not actually destroyed—are in one of two places in the Villa Aurora.”

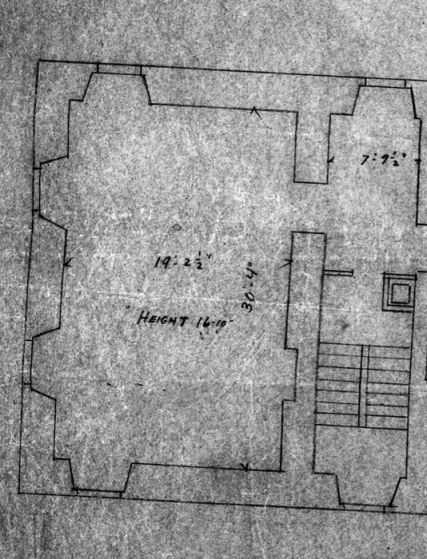

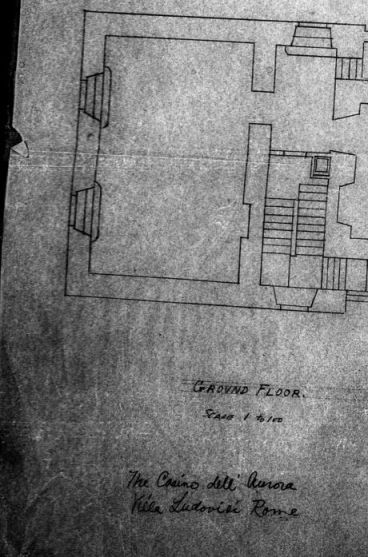

“The first possibility”, continues Brennan. “is that they are lying under the plaster in the ground floor Salone that has the Ottoman frescoes. The second is that they are in the room directly above the Salone, on the piano nobile of the Villa Aurora, and similarly covered over. In the year 1904 that upper room had the same basic floor plan as the lower Salone. Its pavilion ceiling however is higher—a full sixteen and a half feet.” [Editor’s note (2016): that the second location must be correct was demonstrated by ADBL Board member Anthony Majanlahti, and confirmed by endoscope 11 June 2016]

But what about the four framed frescoes and all that stucco work in the ground floor Dining Room? “There’s no easy answer here”, says Brennan. “It’s a fully realized space, with a fresco of Asiatic Istanbul cleverly positioned on the east wall and the European part of the city on the west. But one thing that seems clear is that this Salone underwent a bit of a transformation early in the 20th century. Both the family’s own 1904 floor plan of the Villa Aurora and a contemporary one drawn up by the American Academy in Rome show the Salone with two grand windows. Today there are four. The phase of renovation that brought extra windows to the southwest wall of the Dining Room would have offered one opportunity to redo the ceiling as well, in the form one now has it.”

So the decorations for today’s Salone ceiling are really 20th century? “Well, first one would have to confirm that this room indeed has the Gregory XIII frescoes”, hedges Brennan. “I should think that t-ray [=terahertz radiation] work could readily do that. If this in fact is the sala in question, on my interpretation, the stucco work would indeed be 20th century. About the frescos in the oval and round frames, I don’t know. They may originally be mid-19th century, and repositioned in that room in the Villa Aurora from some other context—say, the family’s Palazzo Grande on the Via Veneto, which the Boncompagni Ludovisi relinquished in 1891, or the Palazzo Piombino al Corso, where Gagliardi and Urtis had already collaborated, but which the family lost to demolition in 1889. I certainly don’t have the technical background to say. But there are plenty of folks who do.” [Editor’s note 2016: you can ignore the above free association since the frescoes are confirmed to be hidden behind later drop ceilings on the second floor.]

Let’s suppose this all checks out. Who do you think covered over the Gagliardi frescoes? “Given the chronology”, said Brennan, “I think it would have to be Francesco Boncompagni Ludovisi who transformed the room. He became Prince of Piombino in late 1911 at just age 25, and held the title until his death in 1955. And since this is a blog, and not the Burlington Magazine, I’ll venture the guess that the renovations took place sometime between 1912 and 1914, before Prince Francesco set off to fight in World War I, from which he returned highly decorated. Still, it’s all pretty odd, since, for one thing, Francesco Boncompagni Ludovisi had a scholar’s interest in the Japanese delegation of 1585—he wrote a book about it. I’m not too worried about the attribution of the present-day Salone to Pietro Gagliardi and Antonio Urtis. That seems just to be a conflation of the facts that the pair are known to have worked in the Villa Aurora from 1855-1858, and that one of the 19th century wings shows fine frescoes and stucco.” [Editor’s note (2016): you can ignore this too.]

And what’s next? “As far as future plans are concerned, that’s up to the Boncompagni Ludovisi of course. In my view just getting some t-ray analysis of the walls of the rooms in question would be quite enough”, offered Brennan. “After all, it’s not the “Battle of Anghiari” we’re talking about. But still the story of the lost Gagliardi frescoes is a pretty gripping tale that illuminates three years in a major Roman painter’s career, and further tells us something entirely new about mid-19th versus early 20th century taste, and changing expressions of Boncompagni Ludovisi family identity.”

Above two photos: details from the American Academy in Rome’s floor plans of the Villa Aurora (ca. 1895-1900). The first shows the Salone in the new (1858) wing on the ground floor; the second, the room directly above it on the piano nobile. Both images courtesy of Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art (NY Research Center)

Corey Brennan warmly thanks (as always) HSH Prince Nicolò Boncompagni Ludovisi and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for their generous assistance in this investigation; and also Joy R. Goodwin, Archives Specialist at the Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art, NY Research Center, for additional help. Brennan stresses that he alone is responsible for errors in fact or interpretation.

In Part III (summer 2016) we will discuss how a combination of Anthony Majanlahti’s minute examination of the Villa Aurora’s floor plans and Corey Brennan’s discovery of further written accounts forced the conclusion that the missing frescoes must be well above a modern drop ceiling in the former salone of the piano nobile, which was spectacularly confirmed on 11 June 2016.

Leave a comment