An illustrated essay by Isabel Heslin (Lehigh ’21)

Almost everyone who has visited Rome has seen the towering, 14 meter high obelisk on its base at the top of the Spanish Steps. It gleams over the Piazza della Trinità dei Monti a bit mysteriously, for the history of the obelisk is relatively unknown.

As it happens, the obelisk used to be the property of the prominent Ludovisi family. They acquired it almost precisely 400 years ago, in 1621, when Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, the nephew of Pope Gregory XV Ludovisi, purchased a large tract of land on the Pincian hill that in the late first century BCE first belonged to Julius Caesar, and then the Roman historian Sallust. These gardens—the Horti Sallustiani—later passed to the emperor Tiberius, and remained an imperial enclave for some centuries to come. We can tell from several threads of evidence that the obelisk was positioned somewhere in the area now demarcated by the Vie Sicilia, Sardegna, Toscana and Abruzzi.

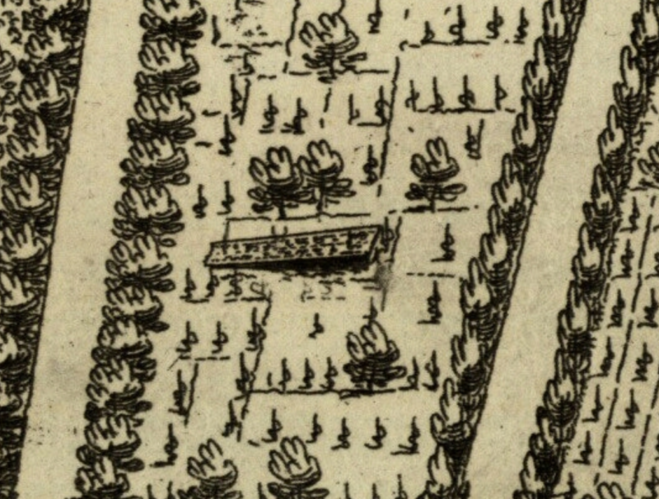

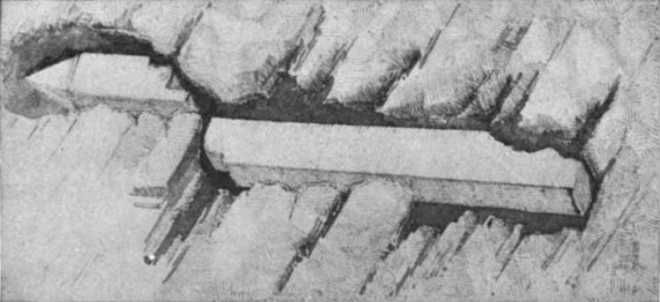

Top: plan of the Villa Ludovisi, published in G.B. Falda, Li giardini di Roma: con le loro piante alzate e vedute in prospettiva (1670). Middle: detail of Falda plan, showing remains of obelisk. Bottom: Google Satellite view of Rione Ludovisi, showing approximate site of obelisk.

There is unfortunately not an abundant amount of primary historical sources written about the obelisk, though it is hoped that future research on the digitized Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi at the Villa Aurora, discovered by HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi in 2010, may offer relevant documents. At present, the best treatment of this obelisk remains Kim J. Hartswick, The Gardens of Sallust: A Changing Landscape (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013) at pp. 52–58, with notes at pp. 165-168; more generally on obelisks in Rome, see B.A. Curran, A. Grafton, P.O. Long, Obelisk: A History (2009).

The only source from the Roman period that mentions this obelisk is the fourth century CE historian Ammianus Marcellinus (17.4.16). After describing Augustus’ importation of obelisks to the city, he notes in passing that “subsequent generations have brought over other obelisks, of which one was set up on the Vatican, another in the gardens of Sallust (in hortis Sallusti), and two at the mausoleum of Augustus.” An item in the Einsiedeln Itinerary (2.7), a late eighth-century guide to the city of Rome written for Christian pilgrims, has in the area of the Gardens of Sallust a “pyramid”—apparently our obelisk—but the notice is too brief to tell whether it was still standing upright.

Detail from Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek, Codex 326(1076) f. 80r (9th/10th century copy of late 8th century text), reporting ‘Thermae Sallustianae et pyramidem’. As for the identity of the ‘Thermae Sallustianae’, as Anna Blennow points out in her attempt to trace this part of the Itinerary, “the Middle Ages were quick to call any grand ruin a bath”.

For much of its time in the ex-Horti Sallustiani, the obelisk clearly was broken into two pieces and left laying on the ground. That was certainly its condition by the early fifteenth century, when it is described as lying broken by its base in a reed thicket (Anonymus Magliabechianus 17). And that is how it remained until the mid eighteenth century.

Two near-contemporaneous renditions of the Ludovisi obelisk from the earliest 18th century. Top: drawing by Carlo Fontana (Windsor 9314) dated 21 March 1706, reproduced in R. Lanciani, The Destruction of Ancient Rome (1899) p. 171. Bottom: engraving in Bonaventura van Overbeek, Les Restes de l’ancienne Rome II (1709, original edition 1708), plate facing p. 17.

Though Egyptian in origin, it is not technically a Pharaonic obelisk. The hieroglyphs that decorate all sides of the obelisk were engraved only after the monument reached Rome. Indeed, they are copies of the hieroglyphs of the obelisk of Rameses II from Heliopolis that Augustus set up in 10 BCE in the Circus Maximus, that today is in the Piazza del Popolo.

In the mid 1730s the obelisk journeyed three and half kilometers south across the city, to the basilica of S Giovanni in Laterano, to join another, larger obelisk originally displayed in the Circus Maximus. Despite ambitious plans to raise the obelisk at the basilica, it sat neglected opposite the Lateran’s Scala Santa for 60 years, only finally to return to a different and topographically dramatic part of the Pincian hill. Eventually, in 1789, it would meet its final resting place after being erected in the Piazza della Trinità dei Monti.

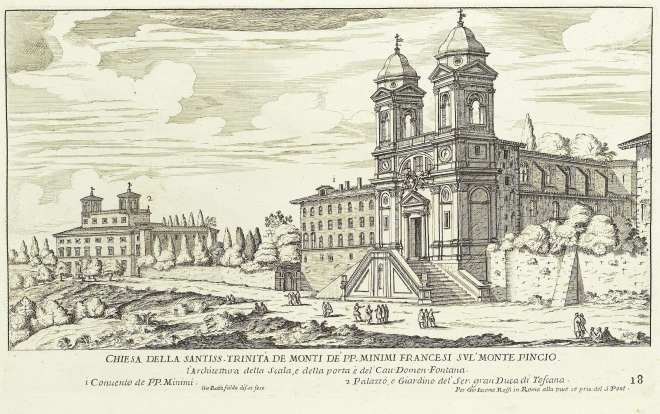

View of Trinità dei Monti, well before the addition of the Ludovisi obelisk, in Giovanni Battista Falda, Il nuovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna III (Roma: G.Giacomo de Rossi) 1669 p. 18.

We have occasional spottings of the obelisk in the 16th century. In 1556 the antiquarian Lucio Mauro (Le antichità della città di Roma p. 83) said it “was dedicated to the Moon, with Egyptian letters.” In 1589 Monsignore Michele Mercari also notes the hieroglyphs, and reports the two pieces that lay near the base were half-buried. (See S. Algieri, I gatti di Sallustio [2016] for the texts.)

Plan, drawn by the architect Carlo Maderno, and oriented to the east, of the Orsini property purchased by Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi in 1621 to form the center of his Villa Ludovisi. From G. Felici, Villa Ludovisi in Roma (1952). His rendition of the obelisk’s remains is indicated by the red circle.

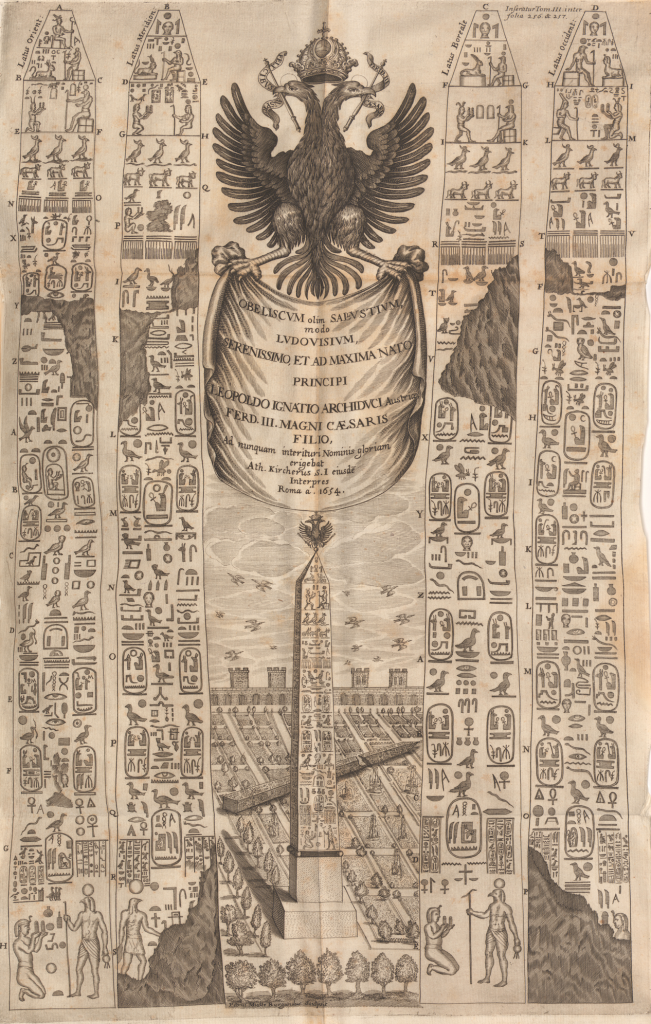

Yet our first detailed account of the obelisk as it stood in the Villa Ludovisi is that of the Jesuit antiquarian and polymath Athanasius Kircher in volume III of his Oedipus Aegypticus, published in 1652-1654, in a chapter entitled “Obeliscus Sallustius seu Ludovisius”. He guesses that the emperor Caligula (reigned 37-41 CE) brought the monument to Rome, and his uncle and successor Claudius (41-54) set it up. Kircher also has much to say on the interpretation of the hieroglyphs. What is the most valuable portion of his narrative is his description of the obelisk’s contemporary location, accompanied by an engraving of the same:

Plate from Athanasius Kircher, Oedipus Aegypticus (1652-1654), facing p. 257, where his account of the Ludovisi obelisk starts.

“At present the [obelisk[ now lies almost completely buried,” writes Kircher, “broken into two parts, in the Villa—exceptionally handsome in its charm and splendor—of the most excellent Prince Niccolò Ludovisi, Duke of Piombino [1611-1664]. This obelisk they suitably call ‘Ludovisian’ from the property’s owner. We have advised that the obelisk be set up as a sort of perennial monument, as it were, of the collected benefits granted toward our Society (of Jesus) by Pope Gregory XV [uncle of Niccolò Ludovisi], a perpetual trophy in honor of the house of Ludovisi, which—so we hope—a future generation will see erected, and will admire as a monument of our illustrious city, in front of the Ludovisian church dedicated in his [i.e., Niccolò’s] lifetime to S Ignatius”, i.e. the Jesuit church of S Ignazio in Rome’s Camp Marzio (founded by Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi in 1626).

Plate(detail) from Athanasius Kircher, Oedipus Aegypticus (1652-1654), facing p. 257, showing idealized view of obelisk in the Villa Ludovisi.

One of the more reliable and accurate of the later sources is an account of the obelisk written by Francesco Cancellieri in 1811 (Il mercato, il lago dell’Acqua Vergine ed il palazzo panfiliano nel Circo Agonale detto volgarmente Piazza Navona), drawn especially from the contemporary Roman newspaper Cracas. He makes it clear that in the papacy of Sixtus V (1585-1590), the obelisk was still visible in the gardens. We learn that Pope Sixtus V wanted to erect the statue near his Acqua Felice fountain, but his pontificate was cut short and he never was able to set it up. There were many possible destinations for the obelisk for which the author provides dates and canceled arrangements. The important thing is that the obelisk passed into the hands of the Ludovisi, and remained with them, unmoved, for over a century.

Papal medal (1733) of Clement XII Corsini (1730-1740), designed by Otto Hamerani, for foundation of the construction of the façade of the Basilica of S Giovanni in Laterano. Numismatica Are Classica auction 118 lot 88 (5 December 2019). For a full discussion of this issue, see the commentary in the Virtus Collection.

Fast forward to 22 March 1733. Pope Clement XII Corsini (1730-1740) asked Princess Ippolita Ludovisi, who then headed the family, if he could erect it in the great piazza at S Giovanni in Laterano. She probably had no choice but to allow him to take it from the gardens of the Villa Ludovisi. But she died (29 December 1733) before the obelisk budged. So on 14 February 1734 we find the Pope commanding Ippolita’s grandson, Gaetano Boncompagni Ludovisi (1706-1777) to turn it over.

“It has come to our attention that in the Villa Ludovisi located in our city, currently owned by Don Gaetano Boncompagni Ludovsi, Duke of Sora, an ancient granite obelisk with hieroglyphics has been found and long excavated, which currently exists above ground broken into several pieces. And since these antiquities concerning the public ornament of the City belong to our Chamber, as gifts from the Supreme Prince, therefore … we command the aforementioned Duke of Sora … that he give the necessary means to be able to extract the aforementioned obelisk from the aforementioned Villa, in order to transport it to the square of Our Lateran Basilica with the purpose of raising it before the facade of the same Basilica … or to another public place at our disposal. No inheritances by primogeniture or trust ordered by any ancestor and author of the said Ludovisi family, although confirmed by this Holy See, are applicable.” [from transcription by G. Felici, Villa Ludovisi in Roma 243 (1952); original = Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 612 no. 16, now in Vatican]

Though the obelisk was moved (apparently in 1736), its restoration at the Lateran never occurred.

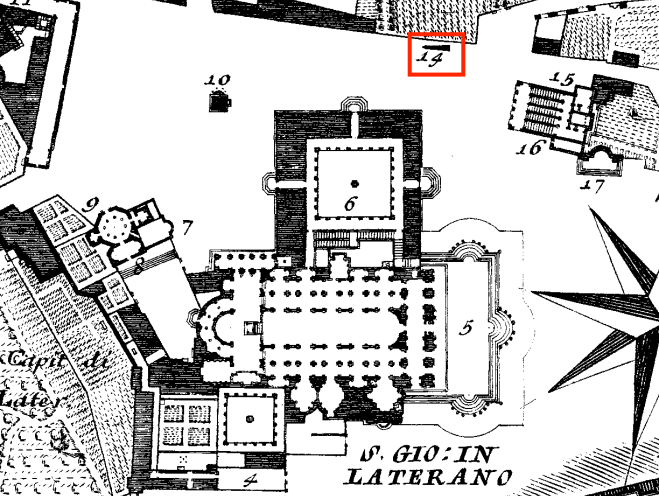

Above: location (#14, marked with red) of Ludovisi obelisk laying on ground at S Giovanni in Laterano in map (1748) of Giambattista Nolli. Below: view of S. Giovanni in Laterano, main façade, with Palace and Scala Santa on the right, by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (ca. 1749). The red rectangle marks the neglected Ludovisi obelisk.

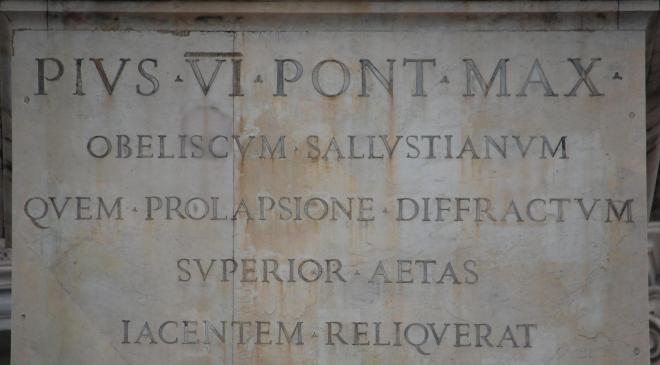

Its final journey took place in 1786, during the pontificate of Pius VI (1775-1799), when the obelisk was moved from the Lateran and erected on top of the Spanish Steps, before the church of Trinità dei Monti. Cancellieri attributes the architectural feat to Giovanni Antinori of Camerino, who indeed is memorialized on the pedestal of the obelisk. One surprising aspect of the story: before Antinori raised the obelisk on the site, he set up a model in canvas first for the Pope’s approval, to see how it would look from various lines of sight.

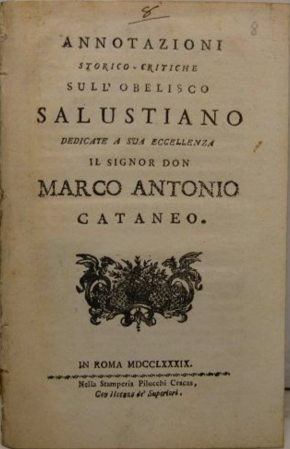

Cover and sample page (showing inscription of Ludovisi obelisk on raising at Trinità dei Monti) in Annotazioni storico-critiche sull’obelisco Salustiano fatte da Nautilo Lemnio Pastore Arcade [= pseudonym for Tommaso Gabrini] (Rome 1789).

Gabrini also tells us that many emperors would have visited the garden of Sallust where the obelisk would have been located. He offers as possible visitors Nero, Vespasian, Nerva, Marcus Aurelius, and Alexander Severus. He eventually concludes with his theory that it was the emperor Aurelian (reigned 270-275) who brought the obelisk to Rome. But he provides very little evidence that this would be the case. It is safe to say that the emperor who first imported the obelisk from Egypt is still remains a mystery.

Aside from the antiquarian misinformation of the pamphlet, there are a few suggestive bits of information that Gabrini offers. We are told that there used to be a circus in the Gardens of Sallust which at one time featured the obelisk in the center, and during the time this pamphlet was written, the late 1780s, it is claimed that the seats and vestiges of the circus were still visible.

Views of the obelisk at Trinità dei Monti (TC Brennan, October 2019).

Though the obelisk had found a spectacular home by the end of the eighteenth century, its ancient base, made of red granite, long stayed in place in the Villa Ludovisi where it awaited a stranger adventure. As K. Hartswick explains, “its whereabouts were unknown until it appeared unexpectedly in 1843 during the removal of the roots of a large, dead tree that stood on the property of the Villa Ludovisia….by the end of the century, when the property of the Villa Ludovisia was in the process of redevelopment for a new quarter of the city, the base was now in the way of progress.” So in 1890 it was moved to an off-site storeroom, where it remained until 1926.

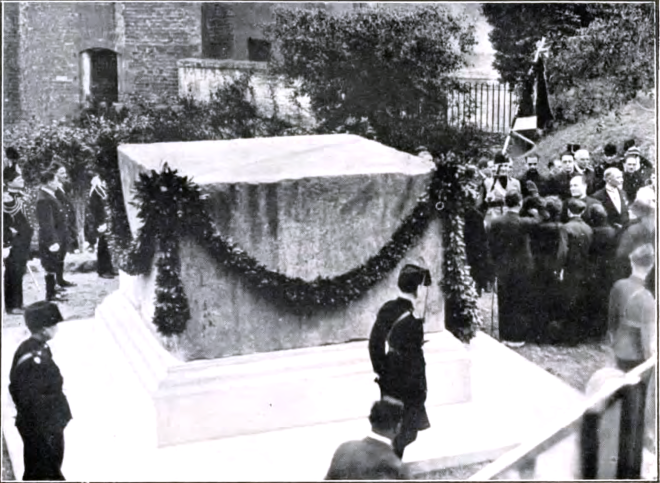

View of the base of the Ludovisi obelisk, now on the Campidoglio, transformed (1926) into the Ara dei Caduti Fascisti, first phase. From Antonio Muñoz, Roma di Mussolini (Milan: Treves, 1935) fig. 49 p. 46.

To mark the fourth anniversary of the March on Rome and the Fascist coup of the Italian government (28 October 1922), Mussolini’s regime moved the block to a small garden on the Capitoline, to the southeast of S Maria in Aracoeli, overlooking the Forum. And there, “with the addition of a base and crowning of white marble,” relates Hartswick, “it became a monument to the fallen of the Fascist regime”, known as the Ara dei Caduti Fascisti. In 1927 the “altar” gained a grandiose inscription: “Questa pietra su colle imperiale di Roma ricorderà nei secoli il sacrificio eroico dei caduti per la rivoluzione delle camicie nere” (“This stone on the imperial hill of Rome will remember over the centuries the heroic sacrifice of the fallen for the revolution of the Black Shirts”).

The Ara dei Caduti Fascisti on the Capitoline, as it appeared on 13 March 1928. From N. Bettegazzi, H. Lamers, and B. Reitz-Joosse, “Viewing Rome in the Latin Literature of the Ventennio Fascista: Francesco Giammaria’s Capitolium Novum“, in Fascism 8 (2019) 153-178

As it turned out, the altar lasted not centuries, but precisely 20 years, for soon after the conclusion of World War II, it was demolished in 1946. The base migrated just a few meters, and now sits discarded on the Capitoline, turned upside down, its Fascist inscription turned away from the path and toward a Roman Republican wall.

Present state of the original base of the Ludovisi obelisk, on the Campidoglio (via Google Streetview).

Tourists will continue to visit Rome and inevitably glance up at the magnificent obelisk and walk through the Piazza della Trinità dei Monti. We know now that the obelisk was in the hands of the Ludovisi family for generations and that it once stood in the center of a long-forgotten circus, and that it was not simply donated to the Vatican as widely reported but instead taken by a process similar to eminent domain. New names, dates, and historical moments will be added to the story, all thanks to groundbreaking discoveries within the newly-digitized Boncompagni Ludovisi archives. Our hope is that more information regarding the obelisk and its history will arise as we continue to learn from this unusually important collection.

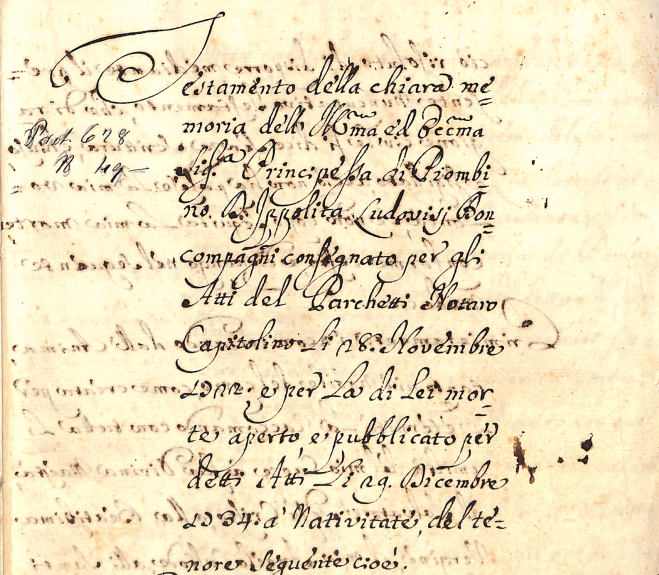

Cover page to last will and testament of Ippolita Ludovisi (died 29 December 1733), composed 28 November 1722 and published 29 December 1734 (Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi Prot. 628 no. 49). Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni, Villa Aurora, Rome.

About the author: Isabel Heslin is a junior at Lehigh University in Bethlehem Pennsylvania, with majors in Classical Civilizations and Anthropology and a minor in History. A member of the inaugural internship class (summer 2020) of the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi, this is her first research project that will also include a publication and she hopes to continue research in ancient civilizations, especially those of Greece, Italy, and Egypt. She thanks Professor T. Corey Brennan for suggesting her research topic and assistance with research and her publication. She also thanks HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for allowing her to conduct research within her family archive.

The church of Trinità dei Monti, ca. 1870 (James Anderson).

Fascinating and to think the toppled fragments were monumental enough to be depicted as they migrated from location to location!

Fascinating timeline, so well written and illustrated.

Excellent reconstruction of the history of the obelisk. A real detective work! Congratulations for telling such an interesting story.