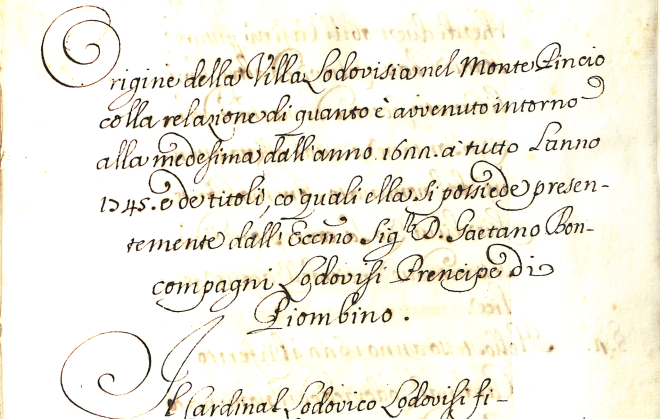

Detail from first page (1R) of the Villa Ludovisi account book (Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi Prot. 365). Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Villa Aurora, Rome.

An illustrated essay by Jacqueline Giz (Rutgers ’24)

One of the most promising items to come out of the Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi at the Villa Aurora, discovered in 2010 by HSH Princess Boncompagni Ludovisi and conserved through her efforts and those of her husband †HSH Prince Nicolò Boncompagni Ludovisi, is an account book—wholly unpublished—for the Villa Ludovisi encompassing the years 1622 through 1745, and spanning about 1000 pages.

The book—catalogued in the Archive as Protocollo 365—was compiled for Gaetano Boncompagni Ludovisi (1706-1777), the 6th great grandfather of Prince Nicolò Boncompagni Ludovisi, shortly after his accession in 1745 as Prince of Piombino.

The inscription on its cover promises to detail the “Origin of the Villa Ludovisi relating everything that happened from the year 1622 to 1745”, starting from the papacy of Gregory XV Ludovisi (who reigned from 1621-1623) and the cardinalate of his nephew Ludovico Ludovisi, who established the Villa Ludovisi on Rome’s Pincian hill. Oddly, Boncompagni Ludovisi family archivist Giuseppe Felici made no use of this volume in his monumental Villa Ludovisi in Roma (1952). Though its contents naturally overlap with items we know from elsewhere, much appears to be new.

Front cover of Villa Ludovisi account book (Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi Prot. 365), compiled shortly after 1745. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Villa Aurora, Rome.

The thick volume hardly tells us all that we would like to know. Yet it does provide a penetrating glimpse into the lives of the Ludovisi and (after 1681) Boncompagni Ludovisi family at a time of unimaginable wealth but also great turbulence. In particular, it illustrates the family’s struggle to maintain full ownership of their property while fulfilling their promise to fund a suitable funerary monument for Pope Gregory XV Ludovisi and also pay for the building of the enormous Jesuit church of S Ignazio next to the Collegio Romano, begun by Ludovico Ludovisi in 1626, opened in 1650, and consecrated only in 1722.

Bronze foundation medal for the church of S Ignazio, Rome (1626). On the obverse, Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi is depicted kneeling while holding a model of the projected church; on the reverse, the three cascades of water (with a legend derived from Ecclesiastes I 7) invoke the three bars of the Ludovisi family crest. Credit: Numismatica Ranieri Asta 12, Lot 63, 9 December 2017.

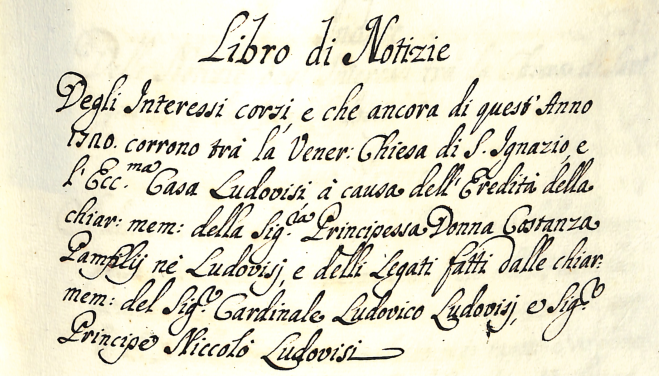

Divided into two sections, and written in at least five different hands, the Villa Ludovisi account book includes detailed records of payments, creditors, and debtors associated with the estate. The first section largely focuses on the will of Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi (who died in 1632 aged only 37) and the family’s creditors. Meanwhile, the second describes the family’s transactions concerning the church of Saint Ignazio—the future home to the tomb of Pope Gregory XV (completed only in 1714).

Detail from introduction to second part of Villa Ludovisi account book (Prot. 365, 154R). Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Villa Aurora, Rome.

Throughout both sections, the book focuses on the children of the younger brother of Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, Niccolò (1613-1664, Prince of Piombino from 1634), all by his third wife Costanza Pamphili, the niece of Pope Innocent X Pamphili (ruled 1644-1655).

Their eldest surviving child—born as grandnephew of the reigning Pope—was Giovanni Battista (or Giovan Battista, or Giambattista) Ludovisi (1647-1699), followed by three sisters: Olimpia (1656-1700), Lavinia (1659-1682), and Ippolita (1663-1733).

Portrait of Giambattista Ludovisi (1647-1699) as a young man, perhaps soon after his accession as Prince of Piombino in 1665. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Villa Aurora, Rome.

Prince Giambattista Ludovisi has an interesting history. When Niccolò Ludovisi died on 25 December 1664, explains Concetta Zarrilli in a recent article, his wife Costanza Pamphili was expecting a fifth child. On 3 February 1665 she made a will, naming as universal heir the child she was expecting. If a boy, his name would be Niccolò, and he would get everything; if a girl, she would have had to share her inheritance with her sisters (then aged 9, 6 and not yet 2 years). Giambattista was excluded from the inheritance. Sadly, precisely two months later, Costanza died in childbirth, nor did her infant son survive. So at the age of 18 Giambattista ended up inheriting all the assets and multiple noble titles of his father, including that of Prince of Piombino.

However, Giambattista clearly managed his inheritance—which as it happens was encumbered by some sizeable debts—poorly, soon leaving him in a less than favorable financial situation. The main adult figure in his life was an uncle, Cardinal Niccolò Albergati Ludovisi, who was legal guardian of his sisters, and as such attempted to hold Giambattista accountable for his actions. For instance, the Cardinal accused his nephew of spending 200,000 scudi in Sardinia on a mistress with the surname Baccaglia, with whom he allegedly had four children out of wedlock. (To get an idea of the gravity of the charge, Ludovico Ludovisi in his will had left 100,000 scudi to build S Ignazio.)

Gold zecchino (1696) minted by Giambattista Ludovisi as Prince of Piombino. Credit: Sincona AG, Auction 29 Lot 1713, 18 May 2016.

This is not the place to tell the full story of Giambattista Ludovisi, who reigned as Prince of Piombino for almost 35 years, as well as holding many other charges (which included even the position of viceroy for the Indies, representing the king of Spain). What concerns us here is how, to alleviate his financial situation, he deaccessioned significant pieces from the Ludovisi family’s esteemed art collection.

Villa Ludovisi account book (Prot. 365), 50V-51R, detailing (at no. 29) the deaccession of “eight paintings” from the Palazzo Grande by Giambattista Ludovisi in 1684. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Villa Aurora, Rome.

Here is where the Ludovisi account book comes in handy. While it is by no means an inventory, the book has several mentions of the transactions involving the Ludovisi family’s art collection. One section (50 V-51 R) dated 25 March 1684 particularly catches the eye, in that there Giambattista declares that he has removed “eight paintings” from the Palazzo Grande of the Villa Ludovisi. He insists he was entitled to do this, as the heir of his recently deceased sister Lavinia (who died 31 December 1682, at age 23).

The passage is worth citing in full. First, in a marginal note in Latin—listed as item “Number 29”—we read:

[Num. 29. Alia recepceta, seu declaratio d(omin)i Principis Ioannis Baptistae super amotione octo Tabularum pictarum a d(omin)a Villa per ipsum facta.]

Then comes this first-person declaration:

Io infrascritto Prencipe Ludovisj ho preso di propria autorità nel Palazzo della villa Pinciana, otto quadretti, cioè uno di Circe, che si dice di Guido di palmi quattro in circa: Uno in tavola d’una Madonna, che dà à Christo la benedizione di palmi due e mezzo in circa: un altro in tavola con tre spartimenti della circoncisione di nostro Signore largo palmi quattro in circa: uno di una Madonna, S. Giuseppe, e Putto pure in tavola di palm tre in circa: uno d’ un Cristarello e ghirlanda di fiori di palmi due in circa: uno in tavola da testa di una Madonna, e Putto in braccio, e S. Caterina, e sue Cornici, ed una Portiera: quali dichiaro aver preso tanto per porzione di mia legittima, quanto come erede della bo(nae) me(moriae) dell’ Eccellentissima Signora D(onna) Lavinia mia sorella, e per qualsivoglia altro titolo mi spettano, et ad effetto, che Domenico Jacovacci, che ha in consegna dette robe non sia molestato nel render conto, gliene do la presente dichiarazione.

In fede questo dì 25 marzo 1684—

Giovan Batista Ludovisj

Strangely, while claiming he moved eight paintings, Giambattista gives a description of just six, saying he also took their frames, as well as a door covering (portiera), presumably a tapestry of some sort. From first to last:

- Circe by ‘Guido’, i.e., Reni (4 palms or ca. 34 inches long)

- A Madonna giving Christ a blessing, on wooden panel (2.5 palms or ca. 21.5 inches long)

- Circumcision of Christ, on panel, tripartite (4 palms or ca. 34 inches wide)

- Madonna, Saint Joseph, and the Infant Christ, on panel (3 palms or 25.5 inches long)

- The Infant Christ surrounded by a Garland of Flowers (2 palms 0r 17 inches)

- Madonna, the infant Christ, and Saint Catherine, also on a panel, in the ‘da testa’ size (a “head-sized” panel smaller than 3 palms)

- The frames for these pictures, and a door-covering.

The Palazzo Grande in 1650: Israël Silvestre (1621-1691), Veuë du palais de la Vigne de Ludovisio à Rome. Credit: Bibliothèque municipale de Lyon (F17SIL004096).

What follows below is an attempt to identify each of these paintings in previous Ludovisi inventories, and if possible, to find their current-day home. This work could not have been possible without the publication of the 1623 and 1633 inventories of the Ludovisi collection, now in the Vatican Apostolic Archive and brought to light in the The Burlington Magazine respectively by Carolyn Wood (134 [1992] 515-523) and Klara Garas (109 [1967] 287-289, 339-348). Their scholarship has been an invaluable resource and as such it will be referenced throughout the discussion—which given the brevity of this item in the account book, has to remain speculative.

Guido Reni, Bust of a Woman Wearing a Turban (ca. 1640-1642). Minneapolis Institute of Art, 66:38.

The first painting mentioned is Guido Reni’s Circe. Though listed in the most prominent place in this quasi-inventory, this painting has no known modern match. However, it should be a variant of his late (ca. 1640-2) Bust of a Woman Wearing a Turban in the Minneapolis Institute of Art, that was in the Gonzaga collection. The painting dichotomously depicts multiple subjects within its single portrait. Among them are the mythical Greek sorceress Circe and the Christian S Lucia. In both the 1623 and 1633 Ludovisi inventories, a painting of Circe by Guido Reni is mentioned, but it is a larger size (5 palms). On this painting, and still another possible variant attested in 1661 in the collection of Cardinal Mazarin, see S. Pepper, Guido Reni (1984) 302-303 no. 200.

Second, Giambattista Ludovisi moved a painting of a Madonna giving a blessing to the infant Christ. However, the notice is accompanied with no additional information besides its measurements. Given the popularity of the subject matter, identifying this painting is extremely difficult. With further study perhaps it can be matched to a work already documented in a Ludovisi inventory using its size.

A painting of the Circumcision of Christ is the third object to be documented in the account book. While there is relatively little information included in the excerpt besides its size, its unique subject matter aids in identifying the painting. An original painting of Christ’s circumcision by Veronese was in the Ludovisi collection until 1644, when it was sent to Spain.

An engraving of the Circumcision of Christ by Veronese (1529-1588), published ca. 1660 by the de Rossi firm.

However, a copy remained in the Ludovisi collection, by the hand of Pietro da Cortona. According to Garas’ commentary on the 1633 inventory (no. 33), this copy ended up the in Pallavicini Collection by 1713. This painting (or its copy) no longer exists. However, an etching published by Giacomo di Rossi (above) depicts the scene, and claims to be a copy of Veronese’s work. This etching is probably the closest glimpse into the lost painting available today. While the engraver chose to remain anonymous, clear credit is given to Veronese in the bottom left corner of the engraving.

Fourth, we learn of another painting of a Madonna and the infant Christ, this time with Saint Joseph. Given its size (3 palms) and subject matter, there is good reason to think that this matches a painting of the same dimensions featuring the Holy Family noted in Wood’s commentary on the 1623 Ludovisi inventory (no. 168). This painting is said to have been displayed specifically in the Palazzo Grande, hung in its Stanza della Galleria. As in this excerpt, it is noted as unattributed.

The Infant Christ in a Medallion Surrounded by a Garland of Flowers by Pier Francesco Cittadini (1616-1681). On the early 17th century origins of the sub-genre, see A. Lo Conte, Italian Studies 71 (2016) 67-81.

Fifth, the account book mentions a painting of the infant Christ surrounded by a garland of flowers. There are no apparent matches in either the 1623 or 1633 Ludovisi inventories. However, the work of a follower of Guido Reni, the Bolognese painter Pier Francesco Cittadini (1616-1681), precisely fits the distinctive description. The lack of inventory matches can easily be explained as Cittadini was less than twenty at the time of the second inventory. The Infant Christ in a Medallion Surrounded by a Garland of Flowers (ca. 1650) may be the same painting documented. If accepted, this shows that the Ludovisi collection of paintings continued to grow in the mid-seventeenth century, adding contemporary artists to what we may call Old Masters as well as the leading lights of (especially) Bolognese painters of the earlier Baroque period.

Finally, the journal entry refers to a smaller painting on wood of the Madonna and child, accompanied by Saint Catherine. This scene had been popular among artists for generations. Indeed, in the 1633 Ludovisi inventory (Garas no. 94), a work of this subject matter is included, measured at 3 palms, with “S Jerome, another saint, and a bishop” as additional figures, and it is said to be by the hand of Parmigianino.

Parmigianino’s Mystic Marriage of S Catherine from the National Gallery (London), inv. NG6427.

Now, a painting by this artist of the “Mystical Marriage of S Catherine” indeed hangs in the National Gallery (London) today (see above). First attested in the Galleria Borghese in 1694, it was measured also at three palms. But there is reason to believe this painting had been in the Borghese collection as early as 1650, and in any case it does not feature a recognizable bishop. (On the iconography of the reported Ludovisi painting, see Garas p. 344 on no. 94.)

Parmigianino’s Mystic Marriage of S Catherine, from the Louvre (inv. 1992-411).

However in 1992, another work on the subject by Parmigianino came to the Louvre. This unfinished painting from ca. 1529 matches the notice of a S Catherine painting in the account book in both size and subject matter (except that in addition to the Madonna, infant Christ and S Catherine, there is a male figure to the right). What may link the Louvre painting to the account book notice is that it came to Paris directly from the collection of Don Gaspar Mendez de Haroy Guzman, Spain’s ambassador in Rome from 1677–1682, and Viceroy of Naples from 1683 until his death in 1687. Guzman has direct links to the Ludovisi family and had held several ex-Ludovisi paintings in his collection. These facts raise at least the possibility that the Louvre copy of The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine is indeed the former Ludovisi painting.

With this being said, it is impossible not to mention “a Mystic Marriage of S Catherine, a very small work on panel, which is sometimes said to be by Parmigianino”, but in fact was painted as part of an elaborate hoax by the great Annibale Carracci. The small-scale painting was documented in the Palazzo Grande of the Villa Ludovisi before 1678 by the Bolognese art historian Cesare Malvasia, who provides the quote. (On this, see A. Summerscale, Malvasia’s Life of the Carracci: Commentary and Translation [2000] 326 with n. 603.)

While the exact identity of the painting is far from clear—not least since the account book does not add the artist’s name—further exploration into the archives may shed welcome light on this matter. Particularly, unstudied correspondence from Guzman himself in the Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi may solve this matter and others.

Detail from Villa Ludovisi account book, 51R, detailing the surprising removal of the Dying Gaul from the Palazzo Grande by Giambattista Ludovisi. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Villa Aurora, Rome.

It is hard to close without glancing at the next item in the account book, where the identity of the object is not in doubt. Indeed, the entry concerns one of the most famous sculptures that has come to us from antiquity—the “Dying Gaul”, formerly known as the “Dying Gladiator”, widely thought to have been found on the grounds of the Villa Ludovisi, during excavations for its foundation under Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, and included in inventories of 1623 and 1633.

[Num. 30. Testes super amotione à d(omin)a Villa insignis Statuae Gladiatoris fact(a) à Principe Io(anne) Bapt(ist)a]

Noi sottoscritti facciamo fede mediante il nostro giuramento, come nella settimana Santa dell’ anno passato 1689 L’ Ecc.mo Signore Prencipe D(on) Giovan Batista Ludovisj nel Palazzo della villa Pinciana fece di propria autorità portar via l’insigne e famosa statua del Gladiatore spirante, e lo sappiamo per averlo veduto, essendo noi custodi, ed affittuarj di detta Villa e Portinaro. Ed in fede questo di dì 24 Agosto 1690 —

Io Giacomo Giro affermo quanto sopra mano propria.

Io Domenico Ragni affermo quanto sopra mano propria.

Croce † di Giovanni della Dera Portinaro.

This is not a formal declaration by Prince Giambattista Ludovisi. Rather, according to this excerpt, two members of the Villa Ludovisi staff had to swear (on 24 August 1690) that in Holy Week of the previous year (i.e., 4-10 April 1689) they spotted the Prince hauling off the “famous statue of the dying Gladiator” from his Palazzo Grande.

Here we know precisely the context. We have a declaration from the Boncompagni Ludovisi archive (Prot. 611 no. 79) dated 4 April 1689 in which Giambattista Ludovisi pledges the statue to Prince Livio Odescalchi, nephew of then Pope Innocent XI Odescalchi (1676-1689), as security for a loan of just 1500 scudi. We also have a document (Prot. 612 no. 87 Lett. A) that refers to the same oath-taking on the part of staff as here. (Both these items are now in the Vatican, and are cited by Felici, Villa Ludovisi pp. 234-235.)

Bronze medal (1689) for Livio Odescalchi, the nephew of Pope Innocent XI, by G. Hamerani. Credit: Fritz Rudolph Künker GmBH & Co KG, Auction 141 Lot 4524 (19 June 2008).

The statue did eventually return to the possession of the Ludovisi, and Giambattista’s sister Ippolita—now as head of the family—sold it to Pope Clement XII in 1733, shortly before her death. Today, the Capitoline Museums in Rome are home to The Dying Gaul.

While the account book of the Villa Ludovisi was clearly not intended to serve as an inventory, it is hoped that this brief study of just two of its ledger items offers valuable insight into its importance for the study of the family’s art collections. Further study of the book should tell much about the family’s history, habits of collecting, and taste.

Jacqueline Giz is a freshman at the Rutgers University Honors College, seeking to major in Art History and Political Science. She looks forward to continuing her work with the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi, for which she was a member of the inaugural internship class (summer 2020), and thanks Professor T. Corey Brennan for his guidance in this project, as well as HSH Princess Boncompagni Ludovisi for so generously making these documents available for study.

Detail from Francesco Faraone Aquila (1676-1740), Dying Gladiator (= Dying Gaul), plate LXV, 1704. Credit: ARTSTOR

Leave a comment