By Christina Demitre (Rutgers University ’25)

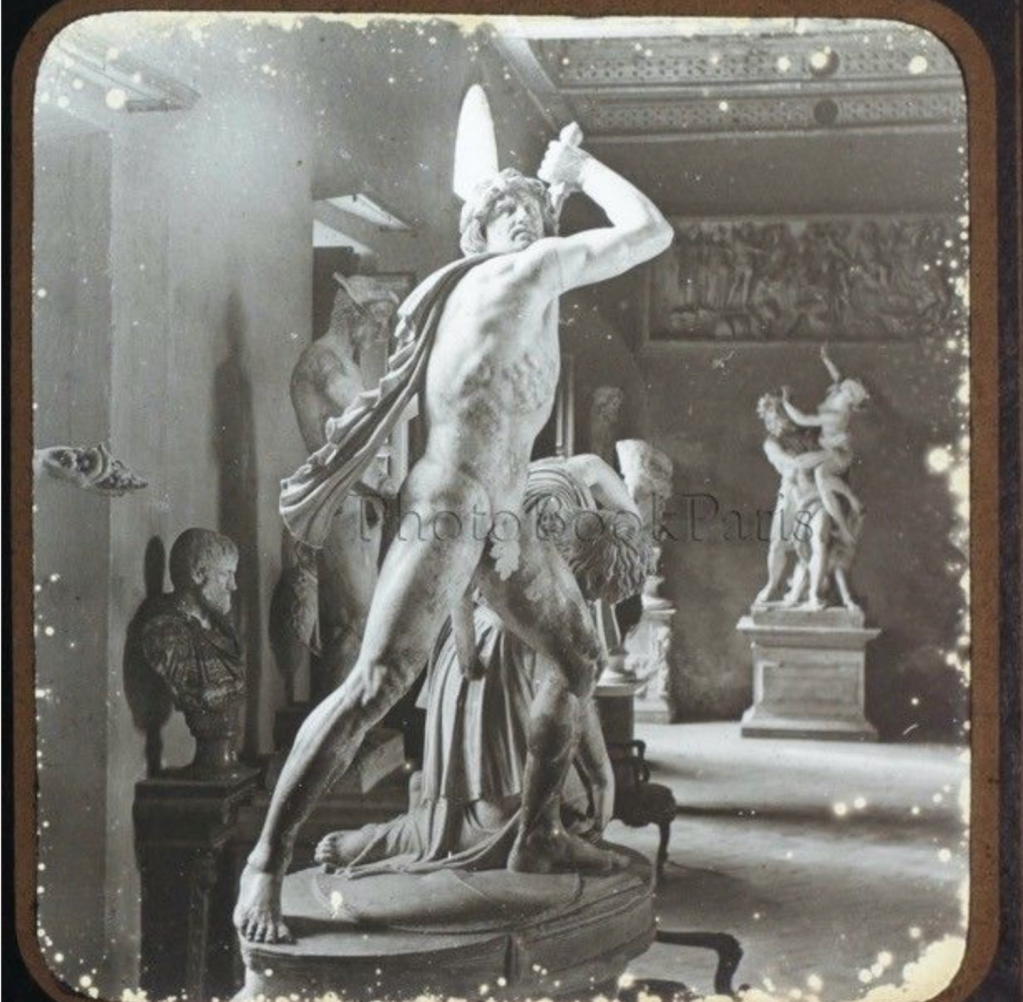

The ‘Re Pastore’ = Amenemhat III (detail) in the Museum of the Boncompagni Ludovisi in Palazzo Piombino on Via Veneto ca. 1890. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Casino dell’Aurora, Rome.

Currently on display in the Palazzo Altemps of the Museo Nazionale Romano sits a curious greenish-grey speckled granite half-statue. Approximately 0.69 meters in height, his faded features elicit somewhat of an elusive expression, having been badly worn from centuries of weathering and deterioration. Upon looking at this incongruous sculpture, one could not help but wonder why this underwhelming piece of art lies amongst some of the most highly prized and most prestigious pieces of Greco-Roman art from the Boncompagni Ludovisi collection.

In fact, this unique sculpture was not of Greco-Roman origin, but is currently believed to be an authentic Egyptian pharaonic bust of the sixth king of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom, King Amenemhat III. King Amenemhat III was widely celebrated for having brought ancient Egypt to its peak of economic prosperity during his 45 year reign in the 19th and 18th centuries BCE. And thus, this historic piece is undoubtedly the oldest piece in the Boncompagni Ludovisi collection of sculptures.

The bust of Amenemhat III in the Palazzo Altemps / Museo Nazionale Romano (inv. 8607). Credit: Jona Lendering, Marco Prins / CC BY 4.0.

It is quite anomalous to have discovered this authentic Egyptian artifact amongst the private collection of the Boncompagni Ludovisi family, which was overwhelmingly composed of Greek and Roman art and sculpture. The Amenemhat III half-bust was the only completely Egyptian piece in the family’s collection. (The ancient obelisk found in the Villa Ludovisi that Pope Clement XII Corsini in 1734 claimed for the Vatican had its hieroglyphs added in Rome.) So how did an authentic Egyptian artifact fall into the hands of the Boncompagni Ludovisi family’s private art collection?

According to the 1877 article titled “Frammento Di Statua D’uno dei Pastori D’Egitto”, the French archaeologist, Assyriologist, and author François Lenormant (1837-1883) presumed that the pharaonic sculpture was originally found in an eastern portion of the Villa Ludovisi added by Prince Luigi Boncompagni Ludovisi in 1825.

But his claim was incorrect. The true “find spot” of the Amenemhat III sculpture was more probably the Campus Martius in Rome, near the Pantheon, where it remained until the mid 1620s. (On its discovery, see the testimony of Pirro Ligorio [1512-1583] cited and discussed in K. Hartswick, The Gardens of Sallust [2004] 190-191.) From this context, it is believed that the sculpture had originally come directly from Egypt and was brought to Rome after the construction of the nearby Temple of Isis and Serapis to be used within the sanctuary.

The ‘Re Pastore’ = Amenemhat III in the Museum of the Boncompagni Ludovisi ca. 1890, in its new (and short-lived) home in Palazzo Piombino on Via Veneto. The inventory number 42 was given to this sculpture at the establishment of the new museum. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Casino dell’Aurora, Rome.

It also can be shown that the Amenemhat III bust was already presiding in the core Ludovisi collection by the mid 17th century, and recognized as Egyptian in origin. This can be seen in a Ludovisi inventory of 1641, where a fragment of an ‘idol in Egyptian stone’ [Frangimento di un idolo in pietra egizia] was identified in the formal sculpture garden before the Palazzo Grande (now US Embassy in Rome) of the Villa Ludovisi.

Plus a 1749 Boncompagni Ludovisi inventory shows that the Amenemhat III half-bust was said to have been situated on a marble pedestal alongside an illustrious “urn” (ie. sarcophagus) depicting the Labors of Hercules [Dalli lati di detta Urna una testa con petto di un Idolo Egizio di pietra di Egitto con pieduccio di marmo, e piedestallo].

It was here, in the so-called “Galleria del Bosco” of the Villa Ludovisi, that the Amenemhat III half-statue remained for decades, attracting the occasional apathetic glance from passersby, authors, and archaeologists, and rarely attracting enough interest to be mentioned in a guidebook.

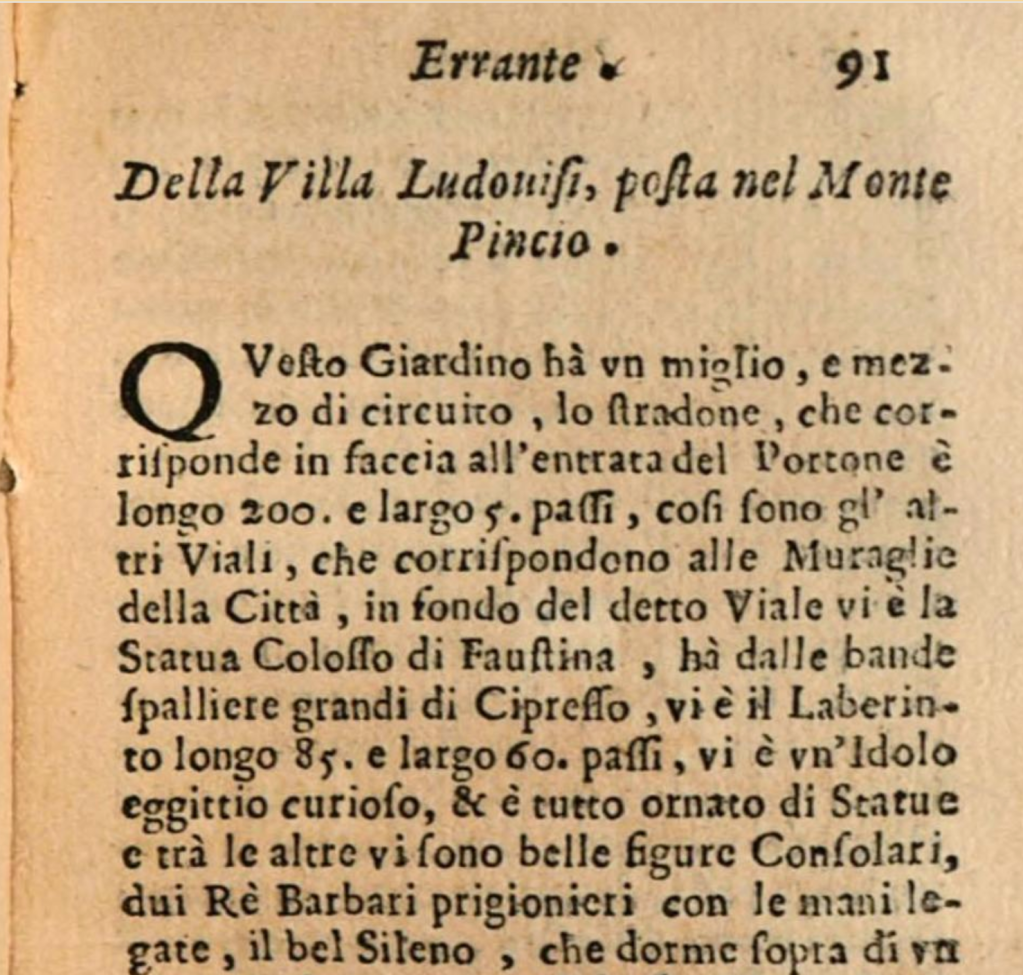

One of the very few guidebooks to have mentioned the Amenemhat III statue was in the influential 1693 Mercurio errante. In it, the author Pietro Rossini briefly acknowledges a “curious Egyptian idol” within the Villa Ludovisi, situated amongst other, more notable pieces within the garden collection. The pharaonic sculpture was again mentioned in passing years later in Giacomo Pinarolo’s 1713 guidebook L’antichità di Roma, in which the author depicts the statues of the Ludovisi garden, describing “two beautiful statues of two barbarian kings as prisoners (=Schreiber nos. 125 and 126), [and a] head of an Egyptian idol”.

The first mention of the ‘Re Pastore’ (“un Idolo eggittio curioso”) in a guidebook: P. Rossini, Il Mercurio errante delle grandezze di Roma (1693).

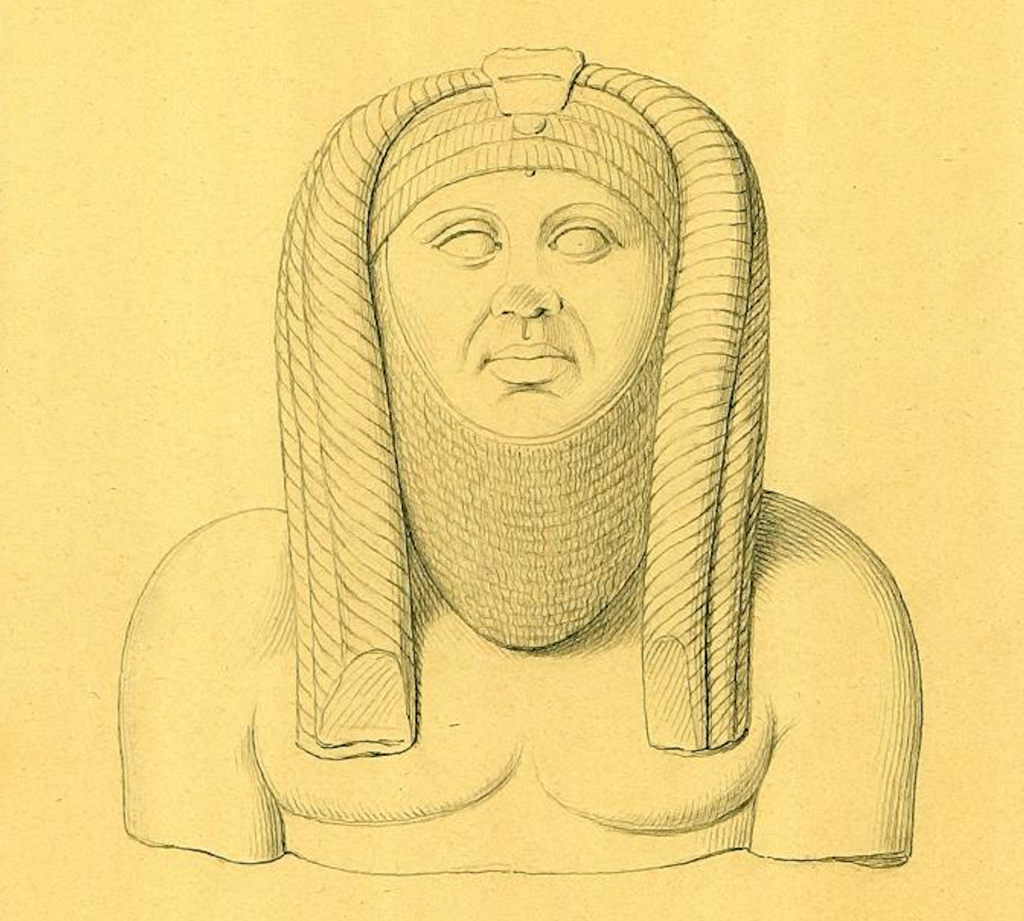

In fact, in very few instances did a guidebook go into further detail to describe the Egyptian half-bust. In those cases, the half-bust was often described as an unnerving, even paralyzing, figure in the Ludovisi garden. his 1744 guidebook titled Le Vestigia e Rarità di Roma Antica”, Francesco Ficoroni depicts a “half colossal head of black marble with a mass of long curly hair around it, which, being of a horrifying expression, isn’t far from being believed to be one of those Deities that scare people”. In an anonymous guide in manuscript from 1789, the author expands Ficoroni’s description: “semicolossal half-bust in black marble with a feminine face, wearing what appears to be a kind of collar around the neck and adorned with very long thick braids on each side, with similar ones behind and a large but flat braid at the occiput. The face resembles that of the Egyptian. Ficoroni believes it was made to create terror.”

Eventually (probably ca. 1806) the Boncompagni Ludovisi moved the Amenemhat III bust indoors, for a new museum of their sculptures in the ex-Casino Capponi (directly to the east of the Palazzo Grande) arranged by Antonio Canova. Here an “Egyptian idol” is listed in an 1819 inventory. In 1842 Francesco Capranesi, in his catalogue of the museum collection, places the Amenemhat III sculpture in Room Two (the more important room) with the inventory number 36. He describes it as a “fragment of a colossal Egyptian Statue in dark green basalt on a shell marble base.”

Sala II of the Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi ca. 1860 (Grillet image), with south wall at left. The statue group of the Suiciding Gaul is blocking the view of the ‘Re Pastore’ sculpture, which was displayed to its right. Photo: Kallimages.

More detail is provided in 1880 by the German art historian and archeologist Theodor Schreiber (1848-1913) in his catalogue Die antiken Bildwerke der Villa Ludovisi in Rom. Here Schreiber offers a complete inventory of all the items in the Boncompagni Ludovisi collection in the order in which they are displayed, room by room, in the ex-Casino Capponi. In the second (larger) room of the gallery on the south wall, between two Roman imperial portraits, “Nerva” (Schreiber no. 98) and “Macrinus” (Schreiber no. 100), and not far from the Suicidal Gaul group (no. 92), and Juno Ludovisi (no. 104) sat the Amenemhat III sculpture. Schreiber goes on to describe the pharaonic bust in great detail, assigning it his inventory number 99. He reports a greyish-green speckled granite Egyptian bust with a “face (especially the nose and lips), the beard, the headdress on the crown, and the ends of the hanging braids on the chest and back [being] heavily worn”.

Schreiber continues: The figure is preserved up to the chest. The horizontally running cut surface is regularly worked. It is likely that the lower part of the statue was made from a separate block. The moderately shaped body, with the lowered arms firmly attached, is unclothed. The massively developed head hair is treated in a wig-like manner, with four thick, regularly twisted, and adjacent braids on each side of the crown hanging down to the chest, while eight other braids fall symmetrically on the back. Above them is a broader, longer braid (broken off below) that starts at the nape and is braided from there. Above the forehead, the smooth-lying hair is arranged in four rows of curls marked by straight incisions. In the middle, a hair ornament that has become unrecognizable due to wear. The long, oval-rounded beard is segmented by parallel, downward-running wave lines and transverse, also parallel indentations. It appears that the beard is shaved on the upper lip. A related hairstyle is shown in a female figure made from similar material and also life-sized, found in the eastern part of the park (formerly the Villa Verospi)…

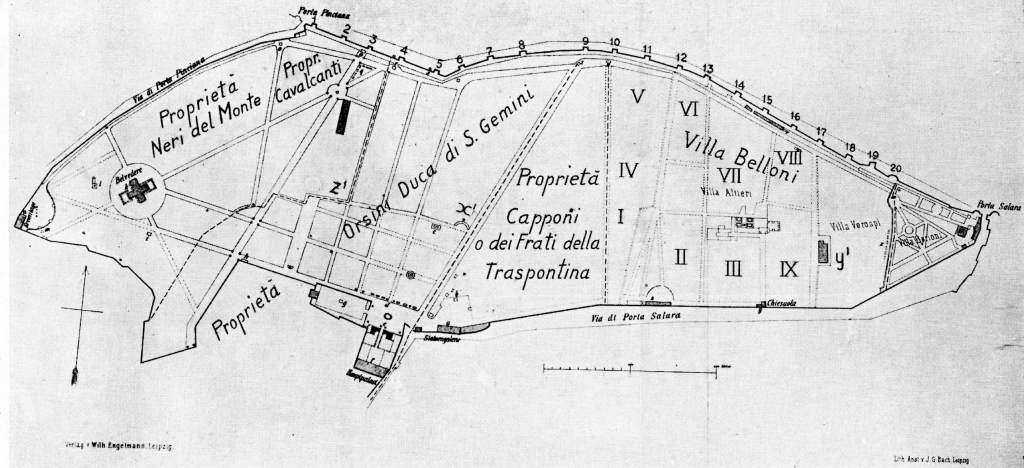

It is noteworthy that Schreiber records that there was a related female figure with a similar hairstyle, made of the seemingly same material, and was similar in dimensions (both being life-sized) to that of the Amenemhat III sculpture. This female figure was found in the eastern part of the park (formerly the Villa Verospi) along with a small group of other Egyptian-styled art that is somewhat similar in color and appearance to the Amenemhat III statue.

Map of Villa Ludovisi from T. Schreiber (1880), with annotations by G. Felici, Villa Ludovisi in Roma (1952). The Villa Verospi is indicated near far right.

This is why Schreiber alludes to the possibility that these Egyptian pieces found at the old Villa Verospi (of which was absorbed by the Boncompagni Ludovisi in 1825 and incorporated into the eastern portion of the Villa Ludovisi) must have been where the Amenemhat III sculpture had been found. But as we had discussed earlier, the Amenemhat III sculpture had already been identified in the Ludovisi inventory of 1641, before the Villa Verospi had been been acquired. Thus it seems highly unlikely that the Amenemhat III sculpture passed into the Ludovisi collection from that find spot.

An important question remains. We have seen that ca. 1806 the pharaonic bust was removed from the gardens of the Villa Ludovisi, where it was exposed to all sorts of weather conditions, and placed indoors in a new family museum space, directly amongst the most prestigious pieces within the family’s collection. What had contributed to this sudden change of heart towards the desirability of this deteriorated Egyptian sculpture? The answer is, we do not know for certain. Yet a contributing reason may have been the wave of Egyptomania that swept Europe after Napoleon’s campaign against Egypt (and Syria) in the years 1798-1801.

In the event, it wasn’t until 1877, when the widely-renowned archaeologist and Assyriologist François Lenormant published an article “Frammento Di Statua D’uno dei Pastori D’Egitto” that the Amenemhat III half-bust would finally be fully acknowledged for what it truly was; a hidden authentic Egyptian treasure. Within his article, Lenormant provides an in-depth analysis of the age, origin, and potential authenticity of the Ludovisi sculpture fragment. In his own words, “the fragment of a statue in basalt… must be placed among the most important monuments of Egypt that Rome can boast of possessing. It is part of the treasures of art and archeology of which Villa Ludovisi is rich”.

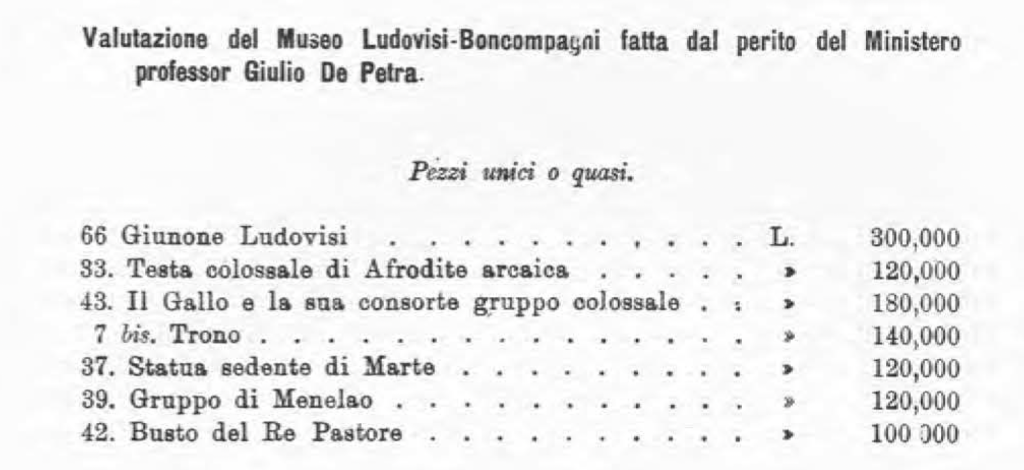

After the 1877 Lenormant publication, the once neglected Egyptian half-bust appears to have appreciated in value ten-fold, becoming one of the most highly prized items in the Boncompagni Ludovisi collection. At the time of the sale in 1901 of the choice pieces of the Ludovisi collection of sculptures to the Italian state for the Museo Nazionale Romano, the appraisal estimate for the “Busto del Re Pastore” or the “bust of the Shepherd King” was officially valued at 100,000 lire. Indeed, we find it listed in state appraisal documents as one of seven “unique” pieces alongside the legendary Ludovisi throne. The Boncompagni Ludovisi family accepted all of the state’s assessments of its sculptures, except for this one item, which the family valued at 300,000 lire (= ca. US $1,579,200 at the time, and ca. US $57,864,332 today). And the price of the Egyptian bust, the Boncompagni Ludovisi family claimed, was non-negotiable.

From the valuation of the Ludovisi collection of sculptures at the time of the sale of many of its most important pieces to the Italian state, finalized in 1901. In the note, one sees that the Boncompagni Ludovisi family rejected only the assessment of no. 42, the ‘Re Pastore’, at 100,000 lire, a sculpture “that it believes is worth 300,000 lire”.

With such a unique and rich history, it was impossible not to shine light on and bring the Amenemhat III sculpture back into the spotlight in the modern-day. Not only is this piece the oldest in the Boncompagni Ludovisi sculptural collection, but the Egyptian Amenemhat III bust’s journey to becoming one of the most prized pieces in that collection is truly remarkable.

Yet interestingly enough, the identification of this unique Egyptian sculpture may still be up for debate. Having previously been listed in the Ludovisi inventory as “Re Pastore” or “Shepherd King”, a term used by the 1st century CE Jewish historian Josephus to denote the foreign rulers that characterized the 15th Dynasty of Egypt, the bust was originally believed to have been a depiction of one of the many foreign kings to have ruled Egypt during the 15th Dynasty between the 17th and 16th centuries BC. These foreign rulers, classically referred to as “Hyksos”, a greek derivative of the Egyptian phrase “hekau khasut” meaning “rulers of the foreign lands”, were particularly notable to the history of Egypt. This period was the first time in which the country was ruled by a foreign body. So it would not be a far stretch to believe that the foreign features characteristic of the Asiatic Hyksos might have showed up on the forms of classical Egyptian style sculpture.

These perceived features of the Boncompagni Ludovisi Egyptian sculpture are exactly what drew François Lenormant to write his important 1877 article on the piece. There Lenormant reflects on a particular dyad sculpture that was found amongst a group of monuments excavated in the early 1860s in the Egyptian site of Tanis by the French archeologist and Egyptologist Auguste Mariette (1821-1881, also honorably known as “Mariette Bey”).

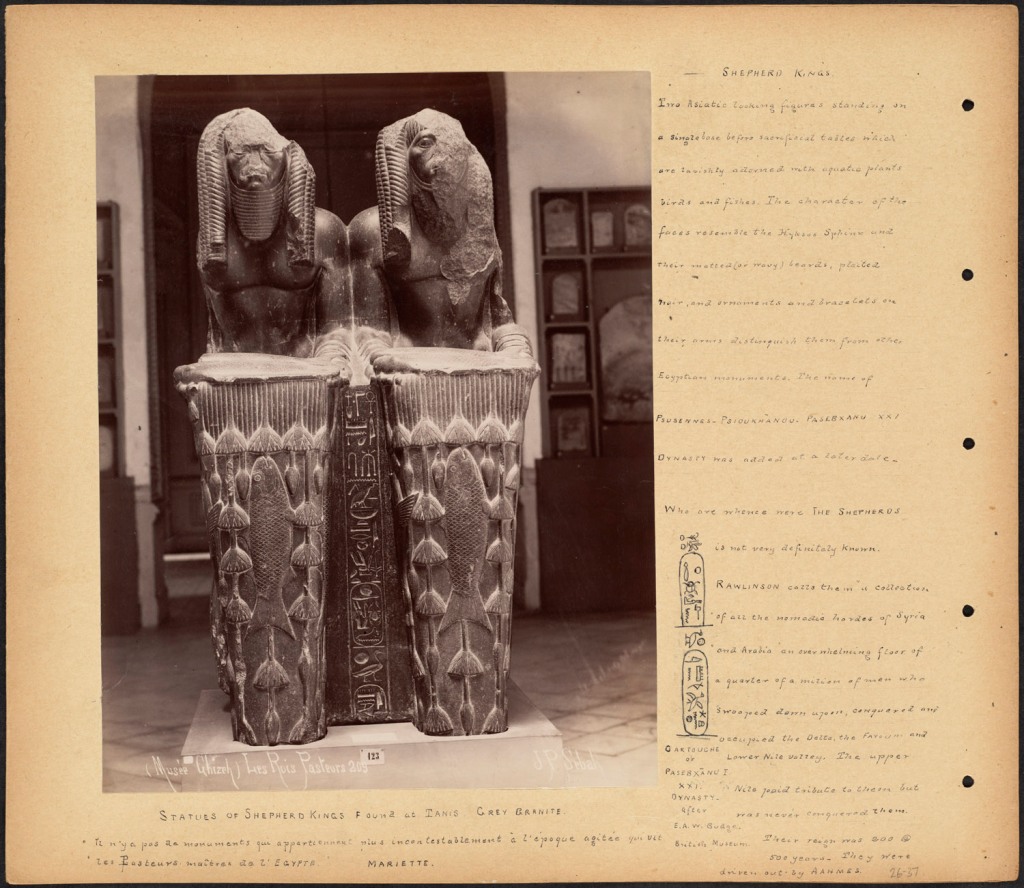

From the scrapbook of William Vaughn Tupper: photograph of a statue of the Shepherd Kings excavated by Mariette with annotations. Credit: Boston Public Library / Wikimedia Commons.

In the first-ever illustrated catalogue of the Egyptian Museum, the 1872 Album du musée de Boulaq by Mariette, this particular dyad sculpture was titled as “Two Statues of Shepherd Kings Found at Tanis [in] Grey-Granite” and was described as depicting “Two Asiatic looking figures standing on a single base before sacrificial tables which are lavishly adorned with aquatic plants birds and fishes”. The top half of the two bodies of this dyad sculpture is strikingly identical to the Ludovisi Egyptian bust, with the exact style of plaited hair, layered beard, and dimensions being exhibited on both statues, and both being made of the same grey-granite material.

Lenormant then goes on to further point out the facial structural resemblance between these two sculptures, arguing that the two male pharaonic figures of the dyad sculpture and the Ludovisi sculpture both had pronounced features that differed from that of the native Egyptians. These include the portrayal of a thick beard on each of the men of the dyad sculpture, whereas traditional Egyptian sculpture never portrayed a full beard, only a false goatee-like beard known as a postiche. The sculpture also portrayed a deep-set nose, high and prominent cheekbones, and wide-set eyes, all characteristic of an Asiatic people.

Therefore, Lenormant concluded that the Ludovisi statue had almost certainly originated from the same group from that of the dyad ‘Shepherd Kings’ sculpture that Auguste Mariette had identified. He further argued that it must also be a depiction of a ‘Shepherd King’ from the temple erected to the god Sutekh by King Apepi, a Hyksos ruler of lower Egypt in the 16th century, at Tanis.

It wasn’t until 1893 that Vladimir Golenishchev (1856-1947), a Russian Egyptologist, questioned the identification of Auguste Mariette’s so-called Hyksos Monuments (and thus, the Ludovisi “Shepherd King”). He proposed that these Hyksos Monuments may not have actually been Hyksos at all. Instead, he argued that the Hyksos Monuments, of which included four maned-sphinxes, a Hyksos king from Crocodilopolis (Mit Fares) dressed in priestly attire, and the dyad ‘Shepherd Kings’ (and potentially our beloved Boncompagni Ludovisi bust!), were all depictions of the popular 12th Dynasty king Amenemhat III.

Sculpture of Amenemhat III in the State Hermitage Museum (inv. # ДВ-729). Credit: State Hermitage Museum.

Golenishchev had based his research on two specific sculptures. One is a positively identified (through inscription) sculpture of Amenemhat III currently located in St Petersburg at the Hermitage Museum (inv. no. 729). The other is an Amenemhat III statue located in Moscow at the Pushkin State Museum (inv. no. 4757)—which was originally part of Golenishchev’s own private collection. By comparing these sculptures with Mariette’s Hyksos Monument sculptures’ facial structures, Golenishchev determined that the Hyksos Monuments follow the same distinctive facial features commonly known to be attributed to the sculpture of king Amenemhat III: prominent high cheekbones, almond shaped eyes, a broader nose bridge, and a pouted mouth exhibiting a highly realistic expression.

Thus, Golenishchev was the first to attribute the so-called Hyksos Monuments to Amenemhet III, and his attribution of the “Hyksos” monuments to be of Amenemhat III became the widely accepted practice. Yet there are still scholars who reject his claim. For instance, the French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero (1846-1916) agreed with Golenishchev’s dating of the sphinxes, but disagreed with the dyad sculpture being of Amenemhat III and instead attributed the dyads to Ramses II.

In 1978, the Coptic Egyptian Egyptologist Labib Habachi (1906-1984) published a further exploration into the identity of Marriette’s Hyksos monuments, in an article titled “The So-Called Hyksos Monuments Reconsidered: Apropos of the Discovery of a Dyad of Sphinxes”. In it, Habachi specifically compares Mariette’s ‘Shepherd Kings’ dyad sculpture (which by this point was presumed to be in the form of Nile gods) and the Tanis sphinxes to a dyad of sphinxes that were discovered in the ruins of the Great Temple of Bubastis.

Images (by L. Habachi) comparing the Tell Basta sphynx with the Tanis sphinx, to support his argument that the Amenemhat dyad sculptures were from the coregency period and were thus two different kings (not duplicate depictions of one king). Full credit in bibliography below.

Habachi concludes that the Tanis sphinxes were depictions of coregent rulers, specifically of Amenemhat III and Sesostris III, and that this could be said for the Hyksos dyad sculpture as well. In this, Habachi was the first to attribute the Hyksos dyad sculpture to the coregency period. This idea of coregency between Amenemhat III and Sesostris III was more recently revisited and explored in great detail just 3 years ago, by Egyptologist Lisa Saladino Haney in her 2020 book Visualizing Coregency, also shedding light on the likelihood of sculpture from this time period being that of coregent rulers.

On our present evidence, Golenishchev’s widely accepted identification of our Egyptian statue as Amenemhat III still seems the most compelling. Yet one huge and perplexing attribute of this Boncompagni Ludovisi sculpture that to this day still puzzles scholars is the sculpture’s full beard, a feature completely unheard of in Egyptian art. In fact, the Ludovisi sculpture is the only one I could find—besides Mariette’s dyad sculpture—of an Egyptian pharaoh bust having a full beard instead of the false goatee-like beard. There are essentially no true beards in ancient Egyptian art/sculpture besides this.

The bust of Amenemhat III in the Palazzo Altemps / Museo Nazionale Romano (inv. 8607). Credit: Jona Lendering, Marco Prins / CC BY 4.0.

With all this being said, the exploration into one of the most valuable and unique pieces in the Boncompagni Ludovisi collection has come to a bittersweet end. The vast history of the Amenemhat III pharaoh bust, namely its tale of rags-to-riches and its potential inconclusive identification of the Amenemhat III bust to this day, has truly made it an inconspicuous star in the Boncompagni Ludovisi collection, and amongst Egyptian art and sculpture as a whole, with such atypical features as its full beard. As scholars offer further research on Mariette’s Hyksos Monuments, I would urge them to include this specific Boncompagni Ludovisi sculpture into the mix.

Christina Demitre (Rutgers University ‘25) is currently pursuing an undergraduate degree in Classics at Rutgers University in the hopes of pursuing Egyptology. In the summer of 2023 she was a member of the internship program of the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi, assisting with the population of the PROVENANCE ARCHIVIO BONCOMPAGNI LUDOVISI ONLINE (PABLO) database, as well as simultaneously conducting extensive research into the understudied Egyptian artifact of the Boncompagni Ludovisi collection, a sculptural portrait of Amenemhat III. She sends a huge thank you to both professor T. Corey Brennan and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for their guidance, and having provided her with such an incredible sculpture to be able to work with and research. She is truly honored for having been included in this stunning opportunity!

MAIN SCHOLARLY WORKS CITED:

Habachi, L. “The So-Called Hyksos Monuments Reconsidered: Apropos of the Discovery of a Dyad of Sphinxes.” Studien zür Altägyptischen Kultur 6 (1978): 79–92.

Hartswick, K. J. The Gardens of Sallust: A Changing Landscape. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004. (See 190-191 for what is known of the discovery of the ‘Re Pastore’.)

Lenormant, M. F. “ Frammento di statua d’uno dei pastori d’Egitto”. Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma (1877): 100-112.

Palma, B. (ed.). Museo Nazionale Romano. Le sculture 1.4: I Marmi Ludovisi, storia della Collezione. Milan: De Luca Editore, 1983 [Villa Ludovisi inventories for 1641 = doc. 16, for 1749 = doc. 31, for 1901 = doc. 55].

Saladin Haney, L. Visualizing Coregency. Leiden: Brill, 2020. (See esp. “The Statuary of Amenemhet III”, at 232–294).

Schreiber, T. Die antiken Bildwerke der Villa Ludovisi in Rom. Leipzig: W. Engelmann, 1880.

Drawing (ca. 1840) by J. Ripenhausen of the ‘Re Pastore’ as it then stood in the Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi. Credit: DAI / Arachne.

PLEASE UNSUBSCRIVE ME FROM ALL EMAILS. I NEVER REQUESTED THIS

Brilliantly written article, on this important and oft overlooked sculpture. Thank you Christine Demitre, Professor Corey Brennan and the support Rutgers University has given us over these many years. None of this would have been possible without Chancellor Edwards.

Thank you so very much! I am forever grateful to you for having allowing me to study and work on such an incredibly invaluable piece from your family’s collection. Many thanks!