An illustrated essay by Katy Greenberg (Rutgers ’19)

A large fresco cycle by Roman painter Pietro Gagliardi (1809-1890) was rediscovered in June 2016 hidden behind a complex mid-20th century drop ceiling on the Piano Nobile of the Villa Aurora. Credit (all fresco photos): Nicholas Brennan, from collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Slowly, a long-lost series of frescoes by Pietro Gagliardi (1809-1890) on the ceiling of the Villa Aurora’s piano nobile is emerging from the shadows. The frescoes, known only from three 1904 photographs until rediscovered in June of 2016, depict scenes from the life of Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni. This blog has previously covered Gagliardi’s depiction of the first Japanese embassy to the west (1585), but so far less attention has been paid to the image of the Pope promulgating his namesake calendar.

Part of decorative setting for Gagliardi’s Calendar reform fresco: Angel in the guise of ‘Fama’

The Julian calendar, which had been the accepted method of timekeeping since 45 BC, gave us a 365-day solar year (with an extra day every four years). However, it was off by approximately 10 minutes and 48 seconds. This may not seem like much, but over the following sixteen and a half centuries, those inconsistencies added up. The end results: all of Europe lagged ten days behind, and Church leaders had a problem of celestial proportions.

Traditionally, Easter was celebrated on the Sunday after the Spring equinox, a practice standardized in 325 by the Council of Nicaea. With the date in chaos, however, something had to be done.

Pope Gregory XIII assembled a team of mathematicians, scholars, and astronomers and tasked them with finding a solution. They used as the framework of their new calendar a proposal by Aloysius Lilius (also called Luigi Lilio or Giglio), a Calabrian mathematician who had died in 1576. On February 24, 1582, Gregory promulgated the Papal bull Inter gravissimas, laying out the workings of the new calendar. In October of that year, he would have ten days completely eliminated; the citizens of Rome went to bed on the fourth and woke up on the fifteenth.

A little less than three hundred years later, Prince Antonio Boncompagni Ludovisi (1808-1883) would hire Pietro Gagliardi to commemorate this event in fresco. Born in 1809, the artist had originally planned on becoming an architect, but after the death of his older brother Giovanni (who had been a painter), he decided to take up painting. He studied at the Accademia di San Luca in Rome under the tutelage of V. Camuccini, G. Landi, and T. Minardi. Gagliardi work would evolve to reflect the Baroque and Neoclassical techniques of his teachers. Eventually, he set up his own studio at the Palazzo Giustiniani.

In 1834, Gagliardi was commissioned by Prince Francesco Borghese Aldobrandini to execute frescoes for the chapel of St. Sebastian at the Villa Aldobrandini in Frascati. Over time, he became best known for his religious commissions.

Notably, he completed some magnificent frescoes for the Basilica di Sant’Agostino in Campo Marzo. He painted, on the crossing dome, the twelve apostles surrounding a seated Christ. He also did work in the nave, including depictions of Old Testament prophets. In side chapels, Gagliardi completed scenes from the lives of Saint Monica and Saint Nicholas of Tolentino.

This is not to say that Gagliardi’s work was entirely religious in nature; he also worked on historical, mythological, and allegorical subjects. He is believed to have completed work for the Palazzo Torlonia (formerly located in the Piazza Venezia, now sadly demolished). An extant image of The Triumph of Venus, dated circa 1836-1837, is attributed to him.

Gagliardi died in 1890, having enjoyed a successful career and the esteem of his patrons. Today, he is not so fondly remembered, his religious art having fallen out of fashion. With so little of his secular art still in existence, the rediscovery of the Villa Aurora frescoes could help to restore Gagliardi’s reputation.

Unpublished photo (1904) of Gagliardi’s Calendar fresco, found in the Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi / Villa Aurora. Collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Gagliardi worked on our scene from 1855-1858. Its setting is the Villa Mondragone, the Pope’s favorite retreat, located twenty miles southeast of Rome near Frascati. The room is filled with the mathematicians, astronomers, and clergymen who created and promulgated the Gregorian calendar.

At left, Bartolomeo Passarotti, Portrait of Ignazio Danti (between 1576 and 1586). Credit: Wikimedia Commons

On the far right, turned slightly away from the viewer, we have the Dominican polymath Ignazio Danti (1536-1586). He was influenced at a young age by his father (an architect) and his aunt (a painter). At age sixteen, he joined the Dominican order and began to study philosophy and theology, later discovering a great affinity for mathematics and astronomy. In Florence, he painted maps and created scientific instruments for Cosimo I de Medici. Before being noticed by Pope Gregory XIII, he served as a professor of mathematics at the University of Bologna. The pope recognized Danti’s talent and invited him to Rome, where he was appointed chief pontifical mathematician, put in charge of the artists working on the Gallery of Maps, and tasked with serving on the calendar commission. Danti did his job so well that in 1583, Gregory thanked him by naming him Bishop of Alatri.

At left, Jacopino del Conte, Portrait of Cardinal Guglielmo Sirleto (1579): Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Seated next to Danti is Cardinal Guglielmo Sirleto (1514-1585), who had been appointed by the Pope in 1575 as chairman of the calendar committee. He was a renowned scholar who also served as custodian of the Vatican Library. It is possible that Sirleto had been the one to bring the work of Aloysius Lilius, the Calabrian mathematician who drafted a proposal for the new calendar before his death in 1576, to the Pope’s attention. Lilius was not one of the prominent thinkers of the day, but he, like Sirleto, hailed from Calabria. This shared heritage may have inspired Sirleto to take a closer look at Lilius’s work.

At left, portrait (by unknown artist) of Cardinal Filippo Guastavillani. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Behind Sirleto stands Cardinal Filippo Guastavillani (1541-1587). A nephew of Gregory XIII on his mother’s side, he was created a cardinal by his uncle in 1574. He would serve, in the course of his career, as Governor of Spoleto, Ancona, Bologna, and Ferrara. From 1584 until his death in 1587, he was Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church, a title later held by Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi. As such, he was in charge of administering the property and revenues of the Holy See. Upon his uncle’s death, he served as the acting head of state for the Holy See until the election of Pope Sixtus V in 1585, and was instrumental in preparations for the papal conclave.

At left, portrait by Lavinia Fontana of Gregory XIII. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Enthroned on the dais, Ugo Boncompagni = Pope Gregory XIII (1502-1572-1585) presides over the scene. He studied—and later taught—law in Bologna before taking vows as a priest. Upon his election to the papacy in 1572, he took the name Gregory in honor of the reformer Pope Gregory the Great. He then set to work trying to live up to the name. He enforced the decisions reached by the Council of Trent, updated the Index of Forbidden Books, and extended his patronage to the newly-formed Society of Jesus. Toward the end of his pontificate, he welcomed the Japanese Tensho embassy to the West (also painted by Gagliardi in the piano nobile of the Villa Aurora). Naturally, he is best remembered for the calendar that still bears his name, which he considered his life’s work. His commitment to this particular reform ensured the stability of the liturgical calendar for the foreseeable future.

At left, Christopher Clavius in a 16th century engraving after a painting (1606) by Francisco Villamena. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Our fourth and final protagonist, shown here kneeling and presenting a copy of the new calendar to the Pope, is German Jesuit astronomer/mathematician Christopher Clavius (1538-1612). He was responsible for making necessary alterations to Lilius’s proposal, creating a functioning calendar that would restore the Easter season to its rightful time. He was able to calculate the time of the Spring equinox and defend his work in an 800-page treatise. When the papal bull was issued in 1582, Catholic countries adopted the new calendar. It fell to Clavius to defend the reform to Protestant critics, one of whom rejected the plan so adamantly that he found it necessary to call Clavius a “German potbelly.” Even though some Protestants (including Johannes Kepler) defended the Gregorian calendar, it would take a long time for Protestant countries to make the switch.

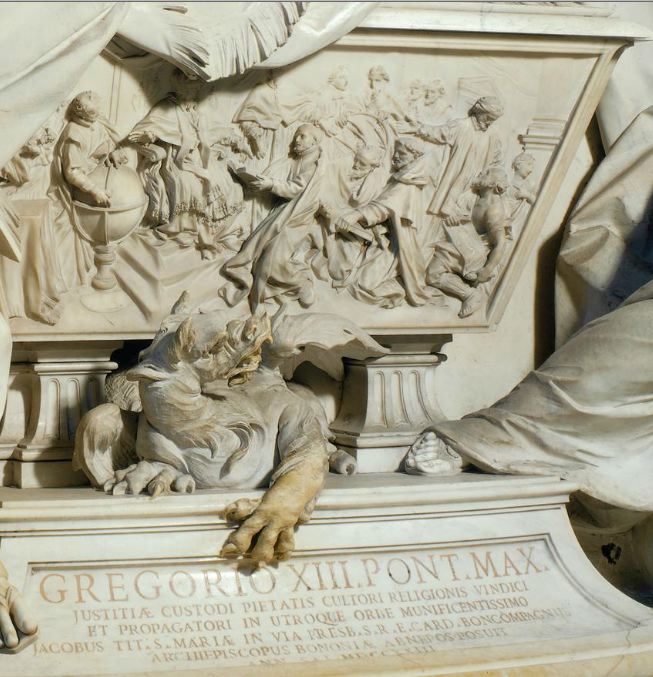

Gregory XIII lived in interesting times and certainly had a busy life, but his reform of the calendar is rightfully considered the crowning achievement of his pontificate. So significant was the scene of the promulgation that, before it was painted by Gagliardi, it was sculpted by Camillo Rusconi in the years 1719-1725 for the Pope’s tomb. The relief image (below the tiara-sporting figure of Gregory XIII and the heraldic Boncompagni dragon) resembles the fresco scene in reverse. It is possible that Gagliardi, living and working in Rome, made visits to the tomb in order to study this image, using it as a jumping-off point for his own work.

Camillo Rusconi’s tomb (1719-1723) for Pope Gregory XIII (2 views), depicting his calendar reform. A large Boncompagni dragon is positioned below the scene. Credits: Wikimedia Commons

Close examination of the fresco is not possible at present, but we hope that future studies of Gagliardi’s work will allow for the identification of more of the figures present in the image. We believe that this fresco could successfully rehabilitate Gagliardi’s reputation, rescuing him from his image as a painter of saint card kitsch, when the ceiling is fully visible and restored.

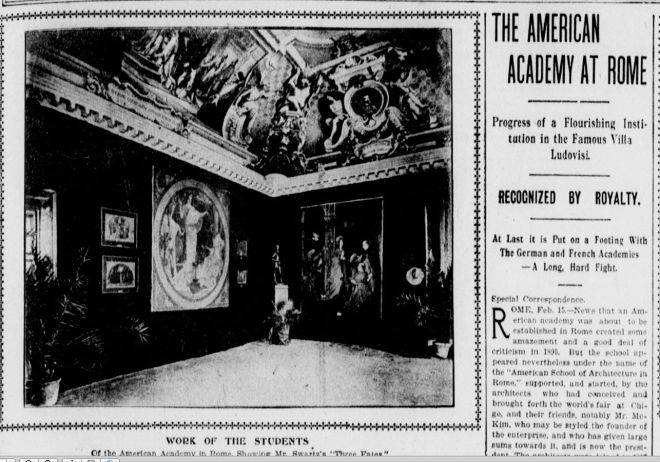

Apparently unique photographic view (1904) of the original Stanza da Pranzo on the Piano Nobile of the Villa Aurora, in this instance filled with a temporary exhibit of artists by the young American Academy in Rome, then renting the premises. Gagliardi’s calendar fresco faces the wall to the left (that is dominated by the scene showing the Japanese embassy), and so is not visible here. Credit: The Deseret Evening News, 27 February 1904.

About the author: Katy Greenberg is a sophomore in the School of Arts and Sciences (Honors College) of Rutgers University-New Brunswick. Katy is working toward her degree in Art History and Medieval Studies; this academic year, as a participant in Rutgers’ Aresty Research Assistant Program, she has been researching the cultural history of the Villa Aurora under the direction of professor T. C. Brennan. Katy is currently looking forward to spending the Fall 2017 semester studying abroad in Florence, Italy.

Pope Gregory was my 17th grandfather, my line coming through his son Giacomo Boncompagna de Crenomo de’ Medici and his wife Costanza Sforza de Santa Fiori and then his third daughter Veronica Boncompagna de Alberti de’ Medici. I would like to talk to anyone who knows about Giacomo and Costanza’s children.