Collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome (this and all MS photos below).

Among the titles of Nicolò Boncompagni Ludovisi, Prince of Piombino (XI), is Patrician of Naples. The origin of this distinction is not in doubt. It was Giacomo (Jacopo) Boncompagni (1548-1612), son of Pope Gregory XIII and 10th great-grandfather of Prince Nicolò, who was first in the family to be entered into the rolls of “Napoli Nobilissima”—more specifically, in the patriciate of the city’s Sedile di Capuana. But a precise date has been lacking, until the recent emergence of a spectacular document of 15 March 1581 in the Boncompagni Ludovisi family archives in their Villa Aurora in Rome.

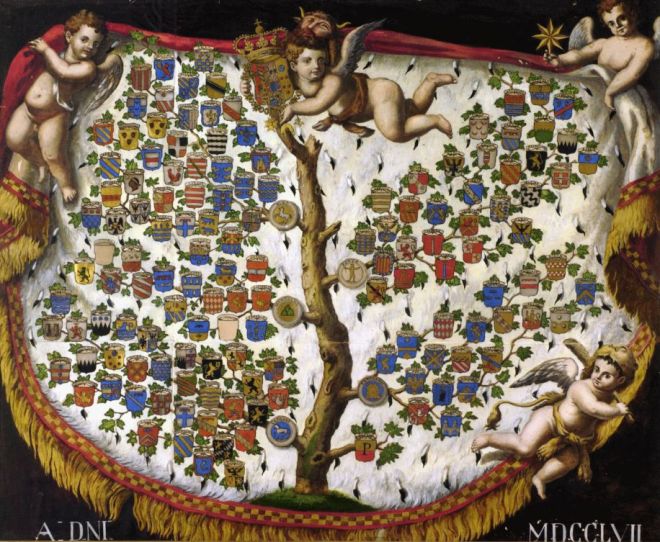

The map of the Duca di Noja (1757), now in the Museo del Tesoro di San Gennaro, showing Naples’ patriciate arranged by Sedile. The arms of the Boncompagni (gold dragon on red shield) are visible in the “Sedile di Capuana” near the end of lowest trunk on left.

First, a word of explanation about the “Sedili” (or “Seggi”, or “Piazze”) of Naples. These Sedili, or “Seats”, functioned as the city’s main administrative units from the mid-13th century to the year 1800. In the developed period there were six in all, with nobles filling five of the Sedili and the ordinary citizenry the remaining one. The representatives of the Sedili, known as the “Eletti”, designated the Magistrati del Tribunale di San Lorenzo, who had a wide variety of civil responsibilities. Ferdinand IV de Bourbon (1751-1825, King of Naples from 1788) however abolished the institution in 1800. The patrician members of the former Sedili now became instead of parliamentarians merely the city’s highest social class, with inscription into the city’s Libro d’Oro. The most comprehensive online list of Neapolitan patrician families, arranged by Sedile, is that of Giovanni Grimaldi here. The Sedile di Capuana takes its name from Naples’ “Porta Capuana“, or rather the quarter nearby this ancient gate positioned at the north end of the city’s historic center.

Second, a reminder about the career of Giacomo Boncompagni. He was born out of wedlock in Bologna in 1548 to Ugo Boncompagni, then a cleric and papal jurist, and one Maddalena de’ Fucchinis, a servant in the employ of Ugo’s sister-in-law Laura Ferro. On the pages of this weblog we have seen how Ugo Boncompagni had his son legitimated, explaining the precise circumstances of his conception in a declaration of 1552 (see here for the autograph document)—six years before Ugo’s consecration as Bishop and 13 years before his creation as Cardinal.

Scipio Pulzone (“Il Gaetano”, 1544-1598), portrait of Giacomo (Jacopo) Boncompagni, dated to 1574. The painting was sold on 30 January 2013 by Christies for almost $7.6 million; the pre-auction estimate ranged from $1.5 to 2.5 million.

Ugo rose to the Papacy on 13 May 1572—as it happens, the last Pope ever elected on the first ballot in the Conclave—and took the name Gregory XIII. In addition to having two Cardinal-nephews in Filippo Boncompagni (elevated 1572) and Filippo Guastavillani (1574), the new Pope energetically promoted his natural son.

On 17 April 1573, Giacomo was made Captain General of the pontifical troops (with charge of the Castel Sant’Angelo), seeing immediate deployment in the area of Ancona, ostensibly against the Ottoman threat. In the following year, his father dispatched him to Ferrara to meet the Polish-Lithuanian monarch Henri de Valois, soon (1575) to be crowned Henry III of France. And in 1575, King Philip II of Spain named Giacomo commander-in-chief of the Spanish armies in Lombardy and Piedmont. (For new documents pertaining to Giacomo’s service under Philip II at Milan in the years 1580-1583, see here.) Further military responsibilities came in 1581. In that year Gregory XIII invested his son, along with Latino Orsini, with full powers to fight brigands in the Papal States, a commission that lasted into 1583.

Costanza Sforza (Parma 1560—Isola di Liri 1617), wife of Giacomo Boncompagni and mother of 14. Photo: collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Giacomo was fortunate in his marriage match—Costanza Sforza, direct granddaughter of Costanza Farnese (daughter of Alessandro Farnese, later Pope Paul III [1468-1534-1549]), and daughter of Sforza Sforza (1520-1575), Count of Santa Fiora and a famed condottiero. The two married in Rome on 5 February 1576 (Giacomo was aged 27, Costanza was probably not quite 16). The entire College of Cardinals attended the ceremony; festivities were held also in Bologna. Together the couple would have 14 children, with Gregorio Boncompagni (1590-1628) as the oldest male child to survive into adulthood and thus able to continue the line. The same year as his marriage Giacomo was made a Patrician of Venice.

What had an enormous material impact on Giacomo’s fortunes was his subsequent acquisition, with his father’s help, of a series of fiefdoms both north and south of Rome, in areas outside the Papal States. One major new title was Marchese of Vignola (5 August 1577), in today’s province of Modena in Emilia-Romagna, purchased for 70,000 gold scudi. Vignola brought with it possession of the imposing medieval castle known as “La Rocca” that is just now exciting much interest for its surprising examples of rediscovered 15th century Italian painting.

Also quite consequential was Giacomo’s creation as Duca of Sora in late 1579. On the important Duchy of Sora and its spectacular castle at Isola Liri, see here on this weblog; Giacomo had bought it from Francesco Maria (II) della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, for 100,000 gold scudi. For some later honors (citizen and senator status at Ravenna, 1581) and feudal acquisitions (particularly Aquino and Arpino in 1583), see this weblog here.

Amazingly, the newly recovered document from 15 March 1581 in which Giacomo Boncompagni entered the patriciate at Naples escaped the notice of even Giuseppe Felice, the family’s last archivist and author of a biography (unpublished) of Giacomo Boncompagni that stretches across nine volumes and 1435 typewritten pages. Felici could merely guess (Vol. V p. 714) that “Giacomo was inscribed in the nobility of Naples, in the Sedile di Capuana, on the specific occasion of his acquisition of the Duchy”, i.e., of Sora. The new document, written in Latin on vellum, shows that patrician status at Naples came fifteen months afterward—but before Giacomo took joint command of anti-brigand operations in the Papal States, replacing his wife’s uncle Cardinal Alessandro Sforza (who died suddenly 16 May 1581).

The document opens with a salutation to Giacomo by the six ‘proceres’ (“chiefs”) and the other patricians of the Sedile di Capuana of the year: Ioannes Antonius Caracciolus, Fabritius Buzutus, Scipio Caracciolus, Mutius Buzutus, Troianus Acciapaccia, et Hieronymus de Marra Capuanae Sedilis fidelissimæ civitatis Neapolis praesenti anno sex viri proceres ceterique sessionis dictae patritii Illustrissimo Jacobo Boncompagno salutem atque felicitatem…. The same six named individuals sign the document at its close, in the following manner and order: Fabrizio Bozzuto, Gio(vanni) Antonio Caracciolo, Mutio Bozzuto, Scipione Caracciolo, Geronimo della Marra, and then (following a noticeable space) Troiano Acciapaccia.

It will be noticed that just four Neapolitan families are represented: Acciapaccia, (Capece) Bozzuto, Caracciolo (Pisquizi), and della Marra. Further investigation suggests that the patricians listed here formed a rather tight aristocratic “ring”.

At the top of the list of signatories, Fabrizio Bozzuto was born 1530 and to die on 19 November 1582. His elder brother was Cardinal Annibale Bozzuto (1521-1565, created Cardinal in the year of his death). Together they were at the core of the nobles who protested in 1547 against the introduction to Naples of the Inquisition. Married to Lucrezia Loffredo, Fabrizio is buried in the Bozzuto Chapel in the city’s Duomo. His relative Muzio Bozzuto (third on the list, a son of Carlo Bozzuto and Isabella del Tufo) is attested in 1587, when the “Eletti” of Naples lent him a large amount of grain from the public granaries. He was married to Faustina Rossi, daughter of Sigismondo Rossi, patrician of Bari, and Laura Caracciolo.

Giovanni Antonio (II) Caracciolo (signing in second position) was the son of Marino (III) Caracciolo and Lucrezia Caracciolo (sic). After his father’s death in 1566, he became Marchese of Bucchianico and (later) Prince of Santobuono. In 1584 he built a monumental palace on today’s Via Carbonara in Naples, now a luxury hotel. Giovanni Antonio was married (30 November 1570) to Diana Spinelli of Cosaletto, and he died on 26 April 1598.

In fourth position Scipione Caracciolo (deceased 3 April 1584) was the paternal grandson of Ciarletta Caracciolo and Ippolita de’ Bastari, and son of Mario Caracciolo and Porzia Pignatelli. Scipione is attested in 1576 as Governor of Naples’ Banca dell’Annunziata, as well as a Cavaliere of the (Spanish) Order of Santiago. He was married to Violante d’Afflito (died July 1578). The fifth signatory Geronimo della Marra (of the noble family long associated with Barletta in Apulia) seems to have died later in 1581 in the siege of Tournai in present-day Belgium, while serving under the Spanish governor of the Low Countries, the Duke of Parma Alessandro Farnese. Finally, Troiano Acciapaccia, the last patrician of the Sedile di Capuana on the list, was married to fellow signatory Scipione Caracciolo’s paternal aunt Maria Caracciolo. He may have been the eldest of all the six “chiefs”.

The Neapolitan authors of the 1581 grant of the patriciate to Giacomo Boncompagni make honorific mention of several other figures in their decree. Twice named is Philip II of Spain (1527-1598) who was also King of Naples from 1554 to 1598. There is also what may be a pointed reference to the Spanish Viceroy of Naples in this period (1579-1582), the nobleman Juan de Zúñiga y Requesens. The Latin text reads: Don Joannes de Zunica Philippi Regis nostri in hoc Regno Vicarius vir gravis admodum animique integritate insignis, fidem nobis fecit, ut tanti hominis virtutum magnitudine capti, obstricti fuimus. (“Don Juan de Zúñiga, viceroy in this Kingdom of our King Philip, a quite serious individual and remarkable for his intellectual integrity, assured us that since the magnitude of the virtues of so great a man captivated us, we were duty bound [i.e., to make him a patrician]).” In other words, it seems the Viceroy told the patricians of the Sedile di Capuna to admit Giacomo to their number.

Finally, the Neapolitans say that in conferring the patriciate they want simultaneously to honor Giacomo and to respond in some way to the benefits conferred by (his father) Pope Gregory XIII (…quod eo consilio fecimus, ut uno atque eodem tempore, tanti viri huius meritis, aliqua in parte responderemus Gregoriique XIII Pontificis maximi beneficiis obuiam pergeremus).

Arms of the Boncompagni. From a genealogy presented to Giacomo’s son Gregorio Boncompagni (1590-1628), Duke of Sora. From the Villa Aurora archives of Prince Nicolò and Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi

The language of the decree is largely formulaic, but it is enlivened by some references to classical literature and history. To evoke Campania’s temperate climate and fertility, the authors turn to a line from Vergil’s famous praise of Italy at Georgics II 150: ubi bis gravidae pecudes, bis pomis utilis arbos (“…where farm animals have two sets of young, and fruit trees have two crops a year”). However, for Vergil’s “pecudes” (farm animals) the authors for whatever reason substitute “segetes” (crops); oddly, this variant is found later (exclusively) in other Neapolitan literature. A paraphrase follows of Georgics II 149 on how in this region “summer heat is not seen at its customary time” (æstasque non suo tempore visitur). Furthermore, Campania is said to have a (presumably healthy) rivalry between “Ceres” and “Bacchus”, i.e., the production of grain and wine (Caereris…et Bacchi assidue est contentio).

Indeed, the authors of the decree express the hope that Giacomo Boncompagni, having landed in this exceedingly pleasant part of Italy, might spend his life there—as did the first century BC Roman commanders Lucius Licinius Lucullus, Pompey the Great, and Lucius Cornelius Sulla (Luculli, Pompei, Sillae exemplo). It is an odd trio to invoke. Lucullus spent part of his final years (66-57 BC) at his villa near Naples, where he became a byword for hedonistic banqueting. Pompey the Great’s most famous association with Campania was that he fell dangerously ill there with fever in 50 BC, recovering only after extensive public prayers on his behalf. Sulla after stepping down from his dictatorship in 80 BC retired to a villa near Puteoli, but there he died—by some accounts, not all that peacefully—after hardly more than a year.

When one adds up these ambivalent references with the fact that the patrician status came to Giacomo Boncompagni a full 15 months after he had become Duke of Sora, and then precisely on the Ides of March 1581 (datum Neapoli idibus Martii Millesimo quingentesimo octuagesimo primo), one wonders whether the powerful Papal son would have suspected the Neapolitans’ enthusiasm. He was an exceptionally learned man with a deep interest (as we will see in a future blog piece) in the sciences, arts and humanities alike. That very year the famed humanist and groundbreaking classical scholar Carlo Sigonio (ca. 1524-1584) was in fact living at Giacomo’s palace in Rome, and writing the history of the Christian church that Pope Gregory XIII had commissioned. But that is another story altogether.

Special thanks to Malissa Arras for transcribing the Latin text of the 1581 Neapolitan document; and to Mahmoud Samori (Columbia University) for additional help deciphering difficult readings. As is usual on this blog site, Corey Brennan can be held responsible for everything else!

Leave a comment