An illustrated essay by Isobel Ali (Rutgers ’22)

Nestled in the Alban Hills of Lazio, less than twenty miles southeast of Rome, lies the inconspicuous city of Frascati. Though known by many as the namesake of the wine produced in this relatively small region, Frascati boasts a rich history that extends back to Republican Rome and beyond, and much of it remains tangible today. Take, for instance, the Istituto Salesiano Villa Sora.

Established by St John Bosco (1815-1888) in 1859, the Society of Saint Francis of Sales, now the Salesians of Don Bosco, is a religious congregation originally founded to aid impoverished children during the Industrial Revolution. Its initial school was created in 1845 in Torino, but the organization rapidly spread, establishing schools around the world. One of the best known locations the Salesians managed to acquire was the Villa Sora, one of the twelve famed Ville Tuscolane, in 1900.

Owing their collective name to their location in the shadow of Monte Tuscolo, this series of villas was built in the old Roman tradition of the landed aristocracy owning country estates that both marked their status and served as places of leisure away from Rome. Though they are spread across Frascati and neighboring Grottaferrata (to its south) and Monte Porzio Catone (to its northeast), these palatial estates unify the region and convey upon it a sense of old nobility, especially when considered in the context of the wider Castelli Romani region.

Indeed, the Alban Hills came to be known under this title for their castles and fortified towns, and though many are private, the properties remain a series of stunning examples of Renaissance and early modern architecture and landscape design. The Villa Sora, like the others, possesses an abundance of these historical attributes. What is more, its status as an operating secondary school allows for a unique opportunity at insight into its history.

While many of these estates bear the family name of their owners—for example, the Ville Aldobrandini, Falconieri, and Torlonia (formerly a Ludovisi possession)—the Villa Sora bears a feudal name, that of the Duchy of Sora. This was a fairly small region in southeast Lazio that resembled a growth at the foot of the Papal States at the border with the Kingdom of Naples. Today the area stands near Lazio’s borders with Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania.

The Duchy of Sora dealt with its fair share of instability. This was partly owed to its historical context: the Italian states of the Middle Ages were notoriously fraught with unrest. But a contributing factor was its ambiguous seat of power, considered to either be the Duke’s palace in the city of Sora, or the fortress at Isola del Liri, less than five miles to the south. In brief, the early history of Sora is one of struggling to gain autonomy and to resist the influence of the Kingdom of Naples, the Aragonese, and other powers vying for control in the medieval Italian states. As with the rest of the states, the Duchy of Sora’s story was often a bloodstained one, and those in power were frequently rotated out, especially in the late 15th century.

Despite fending off attacks like that of the Borgias in the early 16th century, the Duchy exchanged hands a few more times before finding a stable leading family, the Boncompagni of Bologna. In 1579 Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni (1502-1572-1585) bought the Duchy for 100,000 scudi and donated it to his son Giacomo (1548-1612)—the first of many major titles the Boncompagni would amass in the following centuries.

A word of explanation. Due in large part to his desire to moralize the Church—at least visibly—Pope Gregory XIII had chosen not to involve Giacomo in his political maneuvers. Despite legitimizing Giacomo as his son in 1548 (as well as 1552 and 1572), the Pope opted to pass property and money down to his son instead of political power, theoretically cutting down on the nepotism plaguing the church establishment, but still enabling the Boncompagni to build strength.

As it happens, Giacomo had no small career: he served as General of the Holy Roman Church in 1573 before being declared Captain General of the Spanish troops in the State of Milan by King Philip II of Spain in 1575; the latter appointment would create a burning loyalty of the Boncompagni to the Spanish that would last centuries. Following his marriage to Costanza Sforza in 1576, Giacomo was gifted all the Bolognese properties Pope Gregory XIII was holding, and the Pope compounded this by purchasing the Marquisate of Vignola in 1577.

When he purchased the Duchy of Sora in 1579, Pope Gregory XIII was clearly intent on making his son a leader, even if not for his own political gain. The later absorptions of Aquino and Arpino into the Duchy in 1583 were evidence of the continued growth of Boncompagni influence. At the time, all this may have seemed like a land grab by the Papal States. But the purchase of Sora proved to be a turning point for the fortunes of the city and its region, with Boncompagni rule lasting from 1580 through 1796, when the King of Naples Ferdinand IV forced Antonio II Boncompagni Ludovisi (1735-1805) to relinquish control.

As Maria Barbara Guerrieri Borsoi discusses in her essential 2000 work, Villa Sora a Frascati, the precise history of the Villa Sora itself is obscured, seemingly as the result of a series of misfortunes which had fallen upon the owners since its construction. What is known is that the land that would become the Villa Sora —on the Via Tuscolana as one approaches Frascati from Rome to the northwest—was originally owned ca. 1562 by one Angelo di Bernardo Floridi, in the form of a vineyard. Following his death, the property was left to what is now known as the Archconfraternity of the Gonfalone, an organization of penitents who observed rules set down by St Bonaventure.

Not long after, the property was sold to a Giulio Morone for 1800 scudi. Through the generous financial aid of his uncle Cardinal Giovanni Morone (1509-1542-1580), Giulio was able to build up the estate, known at that time as the Villa Torricella, likely for its proximity to one of the small watchtowers that had long since been dotted across the area of Frascati. This would be the third of the Ville Tuscolane to be established, preceded only by the Villa Falconieri (previously the Villa Rufina) and the Villa Vecchia (occupied after 1552 by the Farnese).

No plans of the original Villa Torricella building survive, though it is clear it was much smaller than the modern Villa Sora. Despite this, the Villa Sora and its corresponding estate was one of the most significant villas in Frascati, and hosted Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni. It was still in construction in 1581, when Giulio Morone died, a year after his rich uncle Cardinal Morone. The property soon became a financial burden for the man’s children. Thus, Bartolomeo Morone, one of Giulio’s heirs, in 1600 sold the property to Giacomo Boncompagni, now Duke of Sora for a full two decades.

As was common practice—evidenced by some of the other Ville Tuscolane, not to mention the city of Rome itself—the Villa Sora was built on the bones of its predecessor. Indeed, Guerrieri Borsoi points out that the Morone family may have done the same in their attempts to construct the Villa Torricella. This theory cements both the mystique and longevity of the property.

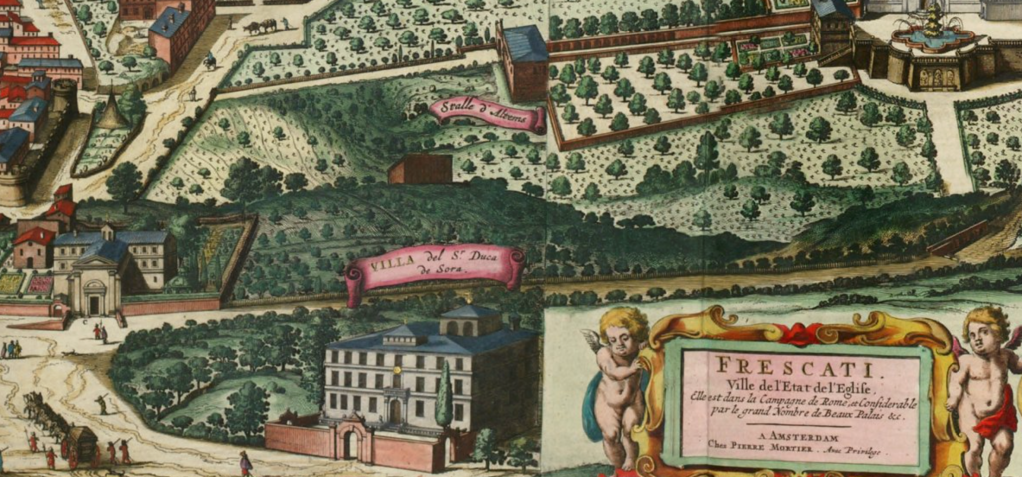

Figurative plan, looking north to south, of the vineyards and thickets in the general area of the Villa Sora allocated by Gregorio Boncompagni. From Antonio Giuliani, Registry (1691) of vineyards at the Villa Sora (Frascati). Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

Upon Pope Gregory XIII’s death in 1585, his son Giacomo Boncompagni left Rome, spending the majority of his time in the territory of Sora, especially at his magnificent castle at Isola del Liri. While he maintained positive relationships with the succeeding popes, his political influence waned and he eventually gave up his position as General of the Spanish troops to focus on his personal interests. Though his income had also decreased significantly since his father’s death, Giacomo still retained the wealth to serve as a patron to many various artists, composers and writers.

Giacomo Boncompagni also took a lively interest in Frascati, which is about 50 miles west of Sora, on a principal route to Rome. When he could no longer rely on the hospitality of the aristocratic families residing in the other Ville Tuscolane, he turned his attention to what would become his own property. So in 1600, Giacomo paid Bartolomeo Morone a mere 9000 scudi for the estate. From here on, the property would officially resign its name as La Torricella, and instead be known to most as the Villa Sora.

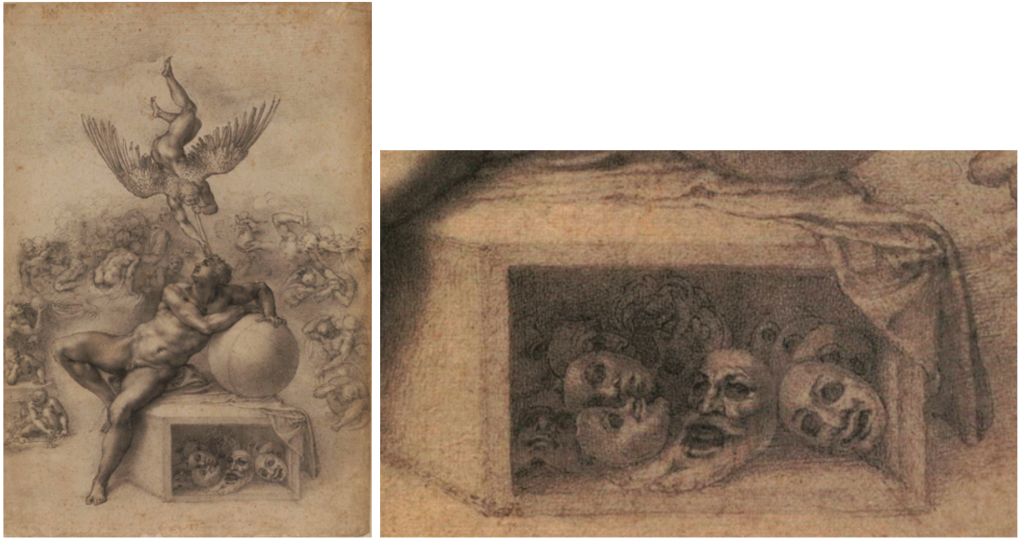

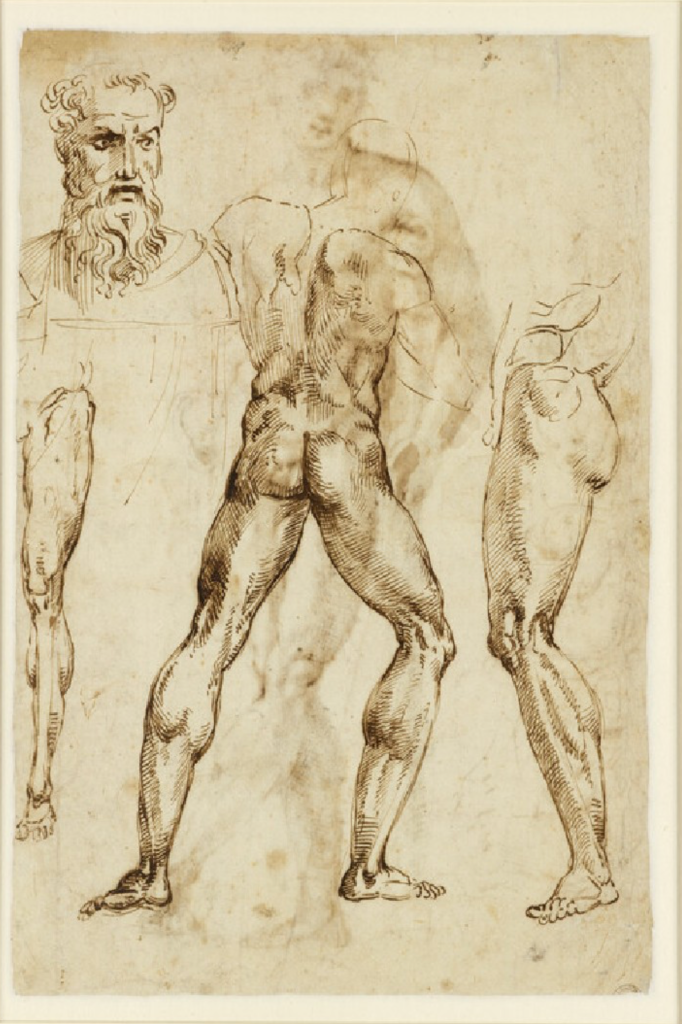

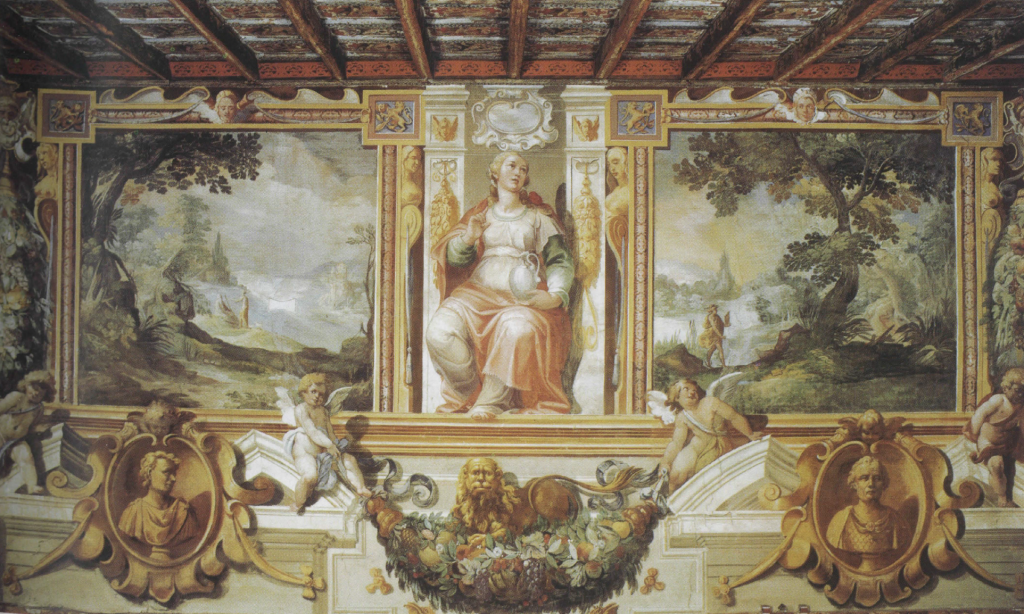

Guerrieri Borsoi rightly describes the focal point of the Villa Sora, its crown jewel, as the series of frescoes adorning the Sala of the Muses. A brief summary of her observations will be provided here, beginning with a clarification of the attribution of the works. Though previously credited as the works of Federico Zuccari (ca. 1540-1609), many subsequent studies by art historians have since determined the primary artist responsible to be Giuseppe Cesari (1568-1640), a Mannerist painter better known as the Cavalier d’Arpino and a mentor to the likes of Caravaggio and Guido Reni.

Guerrieri Borsoi goes on to compare Giuseppe Cesari’s works to those of his brother, Bernardino, before concluding that Giuseppe was undoubtedly the mastermind behind the decoration of the Sala of the Muses of the Villa Sora, potentially in collaboration with Cesare Rossetti (ca. 1565-ca. 1623), a landscape painter. Even without concrete knowledge of the parties responsible, though, the artistry of the frescoes is beyond dispute, and their subject matter is enough to occupy any viewer.

Organized into three registers, the uppermost depicts alternating images of landscapes and seated women; the second depicts garlands of fruit and flowers borne by cherubic figures, here alternating with busts of various male figures; the final register depicts a series of ten figures, alternating with the windows and doors around the hall. Throughout, various decorative elements adorn the walls, quite literally from floor to ceiling. At this point the room is, at the very least, overwhelming; the artistry exhibited in the frescoes entirely absorbs its viewer, surrounding them with larger-than-life figures and plunging them into scenic landscapes. The use of colors is dazzling and the strategic use of the trompe-l’œil imagery that was so characteristic of the Renaissance creates an environment that seems to move and breathe. That, however, is only half the story.

Upon a closer look at the Sala of the Muses of the Villa Sora, a rich world of symbolism begins to reveal itself in even the smallest details. The first images to draw the viewer’s attention are the female figures in the third register: these women, ten in total, are identified via individual symbols by Guerrieri Borsoi as a mix of personifications of some of the liberal arts—Rhetoric, Arithmetic, Geometry—and of other similarly intellectual activities, here described as Dance, Astrology, Philosophy, Heroic Poetry, Lyric Poetry, Comedy, and Tragedy. All of these women are framed in likenesses of marble with gold detailing, evoking the idealized splendor of classical Rome.

As one’s eyes move upward, the garlands of fruits and flowers above the ten women’s heads bring to mind ideas of abundance. Seated in these garlands are alternating depictions of the Boncompagni dragon and the Sforza lion, and interspersed between them are images of the busts of various male figures. The busts are difficult to identify, owing at least in part to the fact that they lack the iconography of the female personifications. Of the ten busts, Guerrieri Borsoi is certain at least one is Cicero, who hailed from Arpino, and that three others are likely to be Homer, Lucullus (the first century BCE commander supposed to have had a villa in Frascati), and Vergil, as a result of either their respective iconography, or their resemblance to other artworks.

Following the gaze of the cherubic figures in the second register upward still, the first register is a corona of seated female figures and pastoral scenes, punctuated by a coat of arms on either side of the room, about half-way down the hall. Here too, one can see the lion and dragon of the Boncompagni and Sforza families, this time in a marriage coat-of-arms. Though the ten women in this register have been identified as the Muses and Mnemosyne due to their iconography, an Apollo figure is conspicuously missing, leading some art historians to misattribute the name to certain other figures.

The landscapes, though, are the most puzzling pieces in the whole room. While some depict mythological scenes, it is uncertain whether they are symbolic references to the Sforza and Boncompagni, or if they are linked to any of the surrounding artworks. Guerrieri Borsoi argues the centrality of the landscape over the human figure creates a sense of tranquility, a fitting purpose for a leisure estate in the country, and a potential reference to the related Roman aristocratic tradition. Just above this register, even the beams share in the symbolism, bearing a faded coat of arms at their center points and edges; their undersides are painted with images of garlands.

What is notably omitted is Giacomo Boncompagni’s history as a political and military figure. The frescoes serve as a stark contrast to his outward life, indicating a more complicated character. The overall message of the room is clear: not only did this property belong to an historic family of wealth and status, with deep reverence for the classical tradition, but the frescoes—which highlight the Boncompagni and Sforza family symbols with roughly equal prominence—were commissioned by a couple with an affinity for the arts and for heroes, a cultured man and his cultured wife.

In 1612, four years after marrying his son Gregorio I Boncompagni (1590-1628) to Eleonora Zapata (1593-1679), Giacomo would die, leaving the property to this son. Unfortunately, the Villa Sora at Frascati would then see little attention for more than a century following. The inventories of this period prove particularly telling, as they show many of the original installations remained, though in increasing disrepair.

Gregorio I Boncompagni largely kept to himself, avoiding politics and spending most of his time on the Isola del Liri near Sora, another component of Pope Gregory XIII’s 1579 purchase, renovated and decorated by Costanza Sforza. Gregorio’s death in 1628 essentially would leave Eleonora Zapata to manage the Villa Sora, first in the name of their son Giacomo II Boncompagni (1613-1636), who died at age 23, and then until her own death in 1679. Though Ugo I Boncompagni (1614-1676), another of Gregory’s sons, came into possession of the villa—still sometimes referred to as “La Torricella” at this point—he ended up selling it to his mother in 1651 for 10,000 scudi as a result of debts he had racked up participating in the 1647 Masaniello revolt and a subsequent series of peasant uprisings.

Eleonora Zapata went on to spend most of her time on the Isola del Liri, and then in Rome. Cardinal Girolamo Boncompagni (1622-1664-1684) would be the next owner of the Villa Sora. As both grand-nephew of Cardinal Filippo Boncompagni (1548-1572-1586, himself nephew of Pope Gregory XIII) and nephew of Cardinal Francesco Boncompagni (1592-1621-1641, son of Giacomo Boncompagni), Girolamo is a somewhat confusing inheritor, only taking precedence through a convoluted rule about first-born heirs. He owned the estate for only about five years; on his death in 1684 it was transferred to his nephew Gregorio II Boncompagni (1642-1707, Ugo’s eldest son).

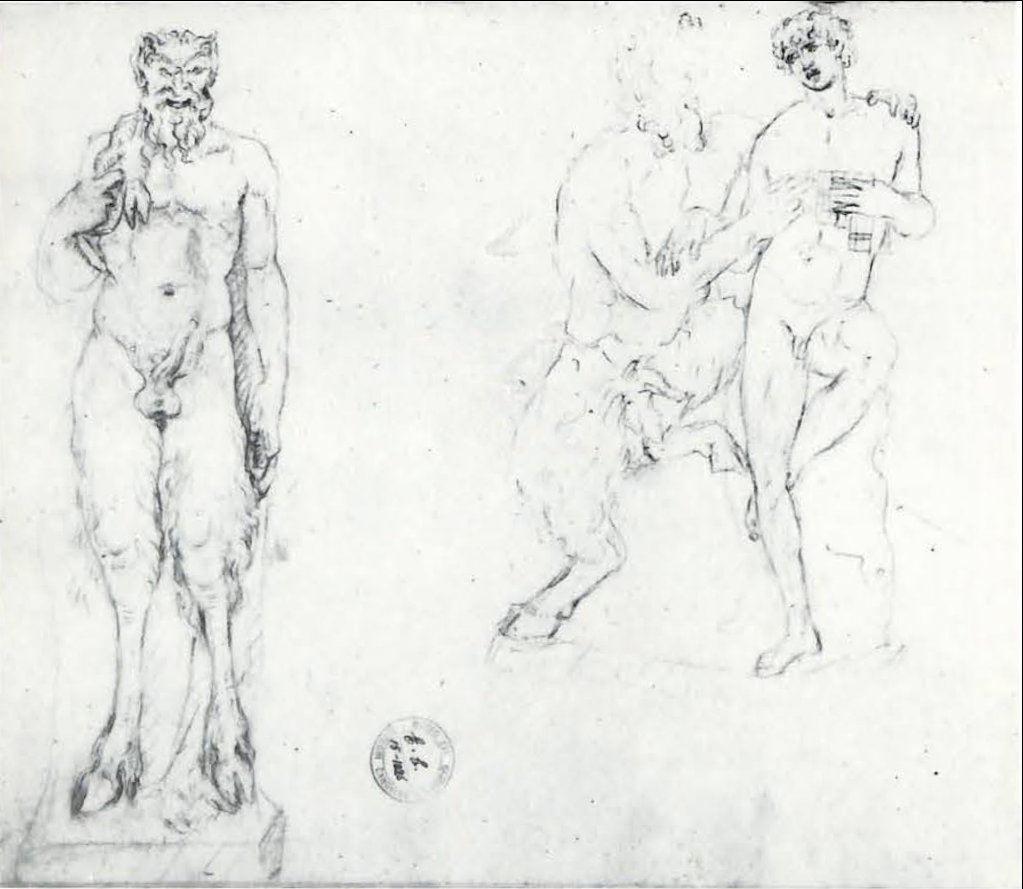

By this point, Gregorio II Boncompagni was an established figure, most widely known for his 1681 marriage to Olimpia Ippolita I Ludovisi (1663-1707-1733), Princess of Piombino, a union that merged the two great Bolognese papal families, the Boncompagni and Ludovisi. For a short time (ca. 1621-1632) the Ludovisi had maintained their own grand Tusculan villa just 1.5 kilometers distant, southwest of the town of Frascati—the Villa Ludovisi, which passed to the Conti and eventually (in the 19th century) the Torlonia.

In order to ensure the security of his family name despite a lack of sons, Gregorio II made the choice to marry his eldest daughter, Maria Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi (1686-1745), to Antonio I Boncompagni (1658-1721), his own brother and Maria’s uncle. On Gregorio’s death in 1707, the property was destined to pass to Cardinal Giacomo Boncompagni (1652-1695-1731) due to another technicality concerning first-born heirs. Though it is uncertain who actually held the Villa Sora at this time—Antonio was primarily located at the Isola del Liri—it is likely that it was Cardinal Giacomo who was responsible for the works commissioned on the property during this time from at least 1714 onward, if not immediately after Gregory II’s death.

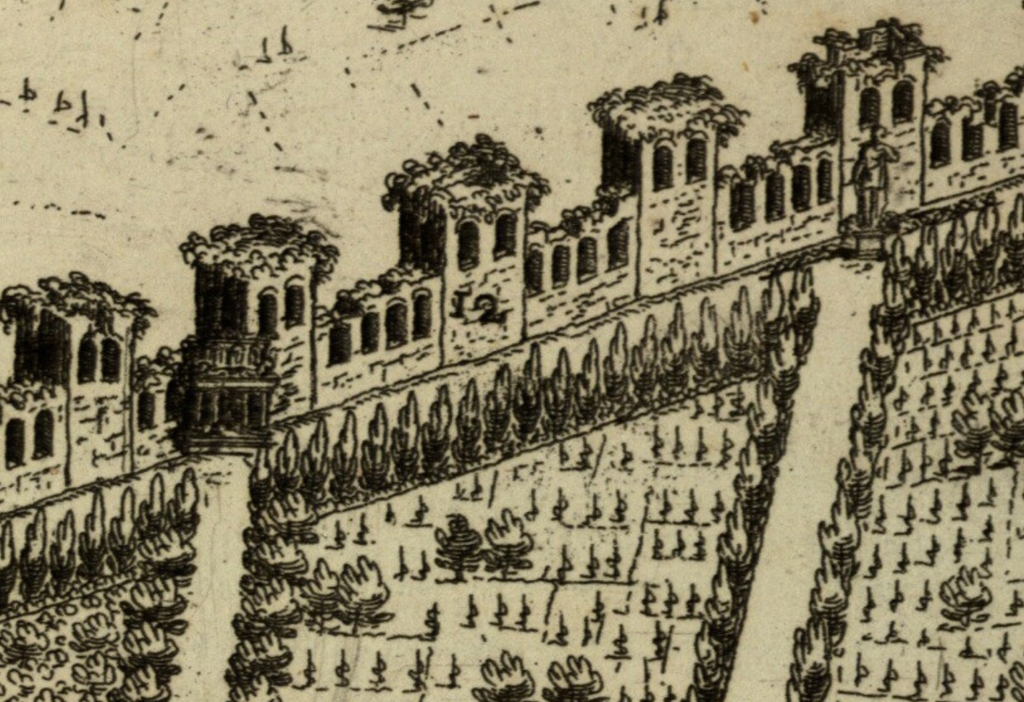

During Cardinal Giacomo Boncompagni’s time at the Villa Sora, the paintings in the sala were restored, and the property’s surrounding landscape, which had long characterized the country villas of the aristocracy, might have been cultivated into a garden, as depicted in the works of Johann Wilhelm Baur (1607-1640) and Melchior Küsel (1626-1684). At any rate, subsequent plans of the property show a central fountain and stables along with a garden. Around this time, it is believed Niccolò Racciolini (1687-1772) was also commissioned to paint scenes of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary and the Trinity in the property’s chapel, a building which had existed since at least 1627.

Neighboring and directly contrasting the chapel was a building defined in a 1716 inventory as a cabinet used for the purpose of what Guerrieri Borsoi describes as “painted hermitage,” which she explains was likely meditation in a simulated hermetic environment, as it was supposed to be decorated with frescoes depicting ruin and isolation. Though the extent of Cardinal Giacomo’s involvement is unclear, he is generally believed to be responsible for the maintenance and additions to the property during this time.

Gaetano Boncompagni Ludovisi (1706-1745-1777) was the next caretaker of the Villa Sora. Though it does not appear that he spent much of his time there—like many Boncompagni before him, Gaetano was deeply entrenched in pro-Spanish politics—the inventories left behind in the wake of his death betray not only his wealth, but an interest in taking care of and preserving the property, while also maintaining the nearby Villa Ludovisi just southeast of the town of Frascati, as well as numerous other holdings in Rome and elsewhere. Over the course of the 18th century, some of the rooms on the ground floor had suffered water damage, but by the time Gaetano died, not only had the water pipes been restored, but a new barn had been added to the property, the fountains were fixed, and there were new additions to the villa itself.

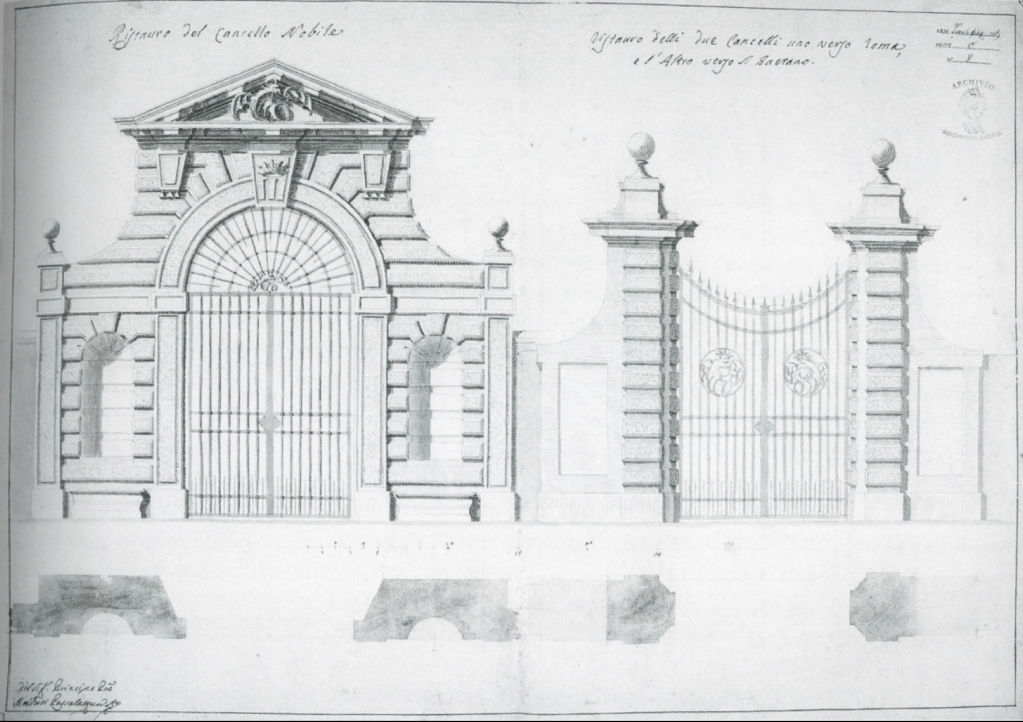

The decorations of the Villa Sora in the 18th century saw a change in theme, with many of the decorations and paintings featuring religious and military iconography, likely to represent Gaetano’s career highlights. Reminiscent of the architectural style of ancient Roman fresco, these paintings open their rooms up beyond the confines of their respective walls, creating the impression of having stepped into another world. Then, in an 1805 inventory drawn up in the wake of the death of Gaetano’s son Antonio II Boncompagni Ludovisi (1735-1777-1805), further details describe what Guerrieri Borsoi dubs the “neoclassical room,” which prominently features mythological scenes and related classical themes. Melchiorre Passalacqua, son of Pietro Passalacqua (1690-1748) and the architect working for Antonio from at least 1777-1805, was also mentioned as being responsible for a series of designs concerning additions to the property, but it remains unclear whether they were ever implemented. What is certain is that this Passalacqua designed a new main gate for the entrance to the Villa Ludovisi, constructed in 1809.

The Napoleonic era brought profound changes to Boncompagni Ludovisi political power. Antonio II Boncompagni Ludovisi had lived through the period of the French Revolution and its aftershocks. Like much of the Roman aristocracy, in this era the family’s power atrophied. In the latter half of the 1790s, he saw Napoleon’s French troops invade the principality of Piombino, which was later integrated into the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, and King Ferdinand IV of the Two Sicilies occupy the Duchy of Sora. Another family feudal property, the Marquisate of Vignola in Emilia-Romagna, was absorbed by the Cisalpine Republic.

Luigi Boncompagni Ludovisi (1767-1805-1841), Antonio II’s son, at the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) managed to hold onto his hereditary titles and was partially compensated for the loss of Piombino; he would go on to reinvest that money in property purchases closer to Rome, seemingly uninterested in the Villa Sora. His son, Antonio III Boncompagni Ludovisi (1808-1841-1883), was similarly unconcerned with the property, so when it finally passed to Rodolfo Boncompagni Ludovisi (1832-1883-1911), it had all but faded into obscurity. By chance however we learn that Luigi’s younger brother, Giuseppe Boncompagni Ludovisi (1774-1849) and his wife Maria Celeste Gervasi had an interest in the property; their daughter Laura was born in Frascati in 1810. It must be stressed that even if the heads of the Boncompagni Ludovisi did not favor the Villa Sora as a residence, they still benefited financially from the produce of its land, as detailed family archival records in the Vatican Apostolic Archive (especially the annual Libro Mastro di Roma) amply show.

Though Prince Rodolfo was the last of the family to own the Villa Sora, scant public evidence remains of his relationship with the Frascati property. His son Monsignor Ugo Boncompagni Ludovisi (1856-1935), in Ricordi di mia Madre, a compendious 1921 memoir of Rodolfo’s wife and his mother Agnese Borghese, altogether neglects to mention the Villa Sora. On Agnese’s trips to the Frascati area—where for instance she sat out an 1854 cholera epidemic—she seems to have stayed at Villa Taverna, a Borghese possession from 1615 until 1896.

Guerrieri Borsoi in her 2000 study of the Villa Sora laments her lack of access to the family archive. As it happens, the cache of tens of thousands of documents brought to light by HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi in 2010 has some previously unknown material on the Villa Sora, filling in some important gaps, and justifying a fresh look at this historic property.

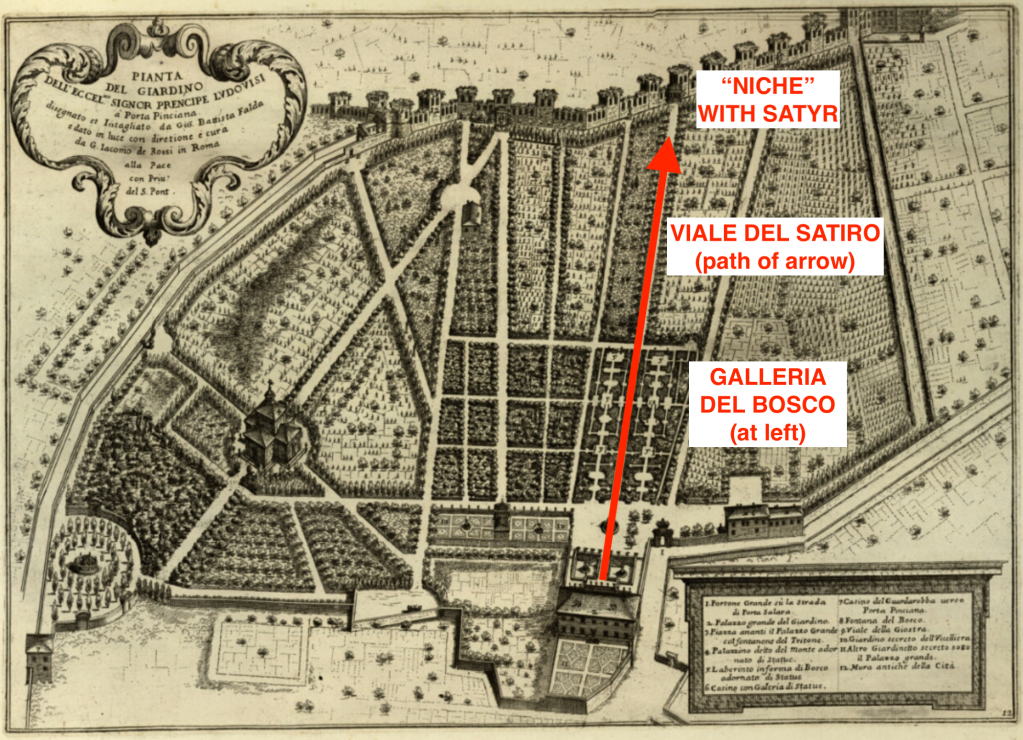

Most spectacular is a 1691 ‘Catasto’ by the surveyor Antonio Giuliani that illustrates the property of the Villa Sora in extreme (and somewhat whimsical) detail, with special attention to renters of Boncompagni vineyards and the rents they paid.

Map with (at left) key of main complex of Villa Sora. From Antonio Giuliani, Registry (1691) of vineyards at the Villa Sora (Frascati). Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

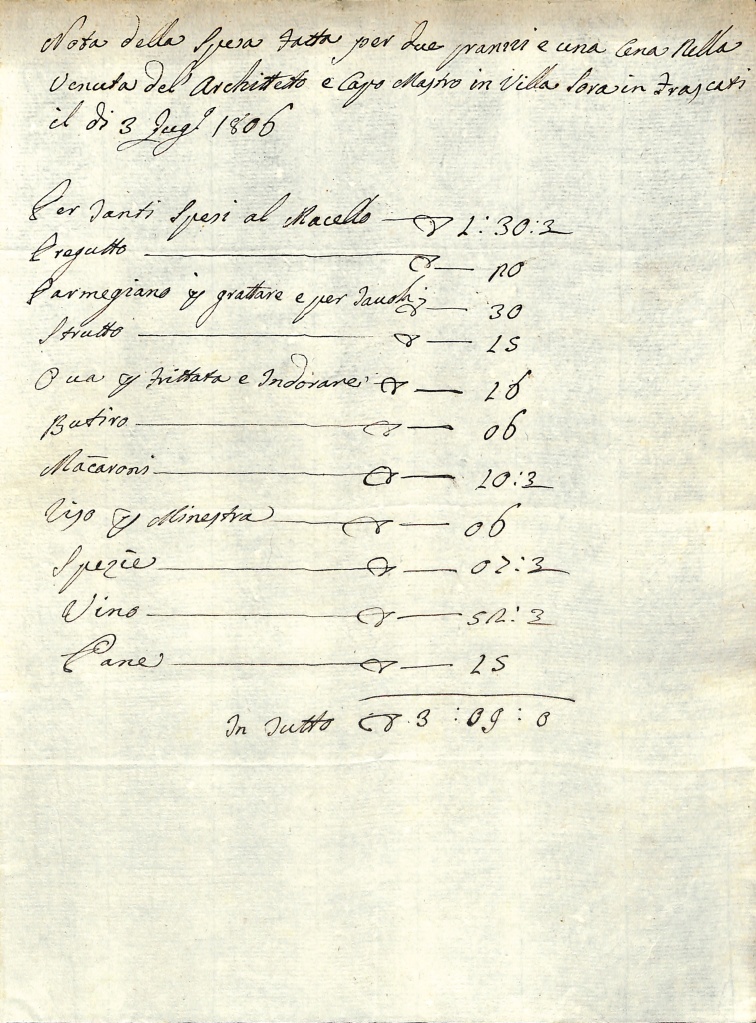

Also of particular note for the general situation in Frascati in the earliest 19th century is a long series of letters from the administrator of the Villa Sora, one Angelo Antonio de Marchis, addressed to Luigi Boncompagni Ludovisi, shortly after his accession as Prince of Piombino in 1805. The letters—sometimes multiple missives are written in the span of a week—contain lavish detail of how French troops were bivouacked at the Villa Sora, as well as more mundane matters. There is even an itemized grocery list from this period (3 July 1806), for the meals (two lunches and a dinner) of the “architect and capo mastro” who worked at the Villa Sora during this time. Angelo Antonio de Marchis was succeeded as administrator by his son, Pietro de Marchis, whom we find in the role by 1822, serving into the early 1830s.

It is with Rodolfo Boncompagni Ludovisi (1834-1911, Prince of Piombino from 1883) that the story of the family at the Villa Sora comes to a close. As attested to in the Vatican Apostolic Archives, on 2 September 1893, Rodolfo sold the now-downtrodden property to Tommaso Saulini for 200,000 lire. And just like that, over two centuries of history—not to mention all the art and architecture that the Boncompagni and Boncompagni Ludovisi had sponsored—were essentially lost. Also, a large number of documents concerning the villa were handed over to Saulini and today remain inaccessible.

Saulini was by profession a hardstone cutter—he was the son of Italy’s foremost artist in that medium—and, along with his own son, made a career specializing in cameos. Guerrieri Borsoi was unable to trace Saulini’s heirs, so she posits that the family was likely attempting to make a profit off the property, and that they sold it a number of times to various owners; whatever their intentions, when the Salesians bought the Villa Sora from them on 28 October 1900 for 32,000 lire, the Villa Sora’s turbulent history was over.

Well, for the most part.

The Salesians’ aims for the Villa Sora involved the construction of a school that would eventually become the Collegio Salesiano Villa Sora. Because the remnants of the once-proud villa were too limited for the scope of the Salesian project, they began adding buildings to the property. In 1905, a section was built against the southern face, and in 1912 an entirely new building was added; by 1926 the latter was connected to the original villa by a two-story hall. In 1933, the addition of a theater and a chapel were initiated, and work continued through 1955.

The renovations might have finished earlier, if not for bombings during WWII. In Rome, on the 13th of August 1943 allied bombs killed over five hundred civilians. Just three months previous, Pope Pius XII had written US President Franklin D. Roosevelt a plea to spare the city of Rome. Roosevelt’s response at the time was to say bombings over Rome and the Vatican were being limited as much as possible. Yet 14 August 1943 saw Rome declared an “open city,” a title generally reserved for cities attempting to spare their infrastructure in the face of imminent capture. Despite Rome’s designation as an “open city”, however, sporadic bombings continued through the end of 1943 and into the beginning of 1944.

On 8 September 1943, the Villa Sora was hit, resulting in the loss of the most recent buildings. The Salesians were quick to bounce back, though, and as the property was restored the villa served as home for many who had been displaced during the war. The school is still operational, and though deeply transformed, the history always manages to peek through.

The Villa Sora, much like its Roman cousin the Villa Ludovisi, upholds the Boncompagni Ludovisi legacy of treasures hidden in plain sight. Whereas the Villa Ludovisi has now entered a state of diamond-in-the-rough obscurity thanks to the rapid division and development of much of the property in the mid 1880s, the history of the Villa Sora—though remaining fairly intact and with its most important features largely unchanged—is mostly forgotten. The reasons? A combination of the Boncompagni Ludovisi using the Villa as a secondary (even tertiary) home, the Salesians’ thoroughly repurposing the property, and the damage brought about during several occupations and World War II. Still, in 2006, the Villa Sora found itself on a tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

If there is any lesson to be learned from the history of the Villa Sora at Frascati, it should be that these works deserve to be protected and cherished as soon as possible—a message with clear relevance to the present situation with the Casino dell’Aurora in Rome. This history belongs to everyone, and it would be foolish to wait, hoping an external group may intervene just in time to protect another integral piece of the Boncompagni Ludovisi legacy.

In conversations about the Boncompagni Ludovisi properties with Rutgers professor Corey Brennan, the late Prince Nicolò Boncompagni Ludovisi (1941-1988-2018) expressed deep regret at the forfeiture of such an important ancestral property, to the point where he would refuse to talk about the Villa Sora. The loss was a wound too deep to be safely reopened. The gaps in the already skeletal outline of the Villa Sora’s history above should be evidence enough that some pieces of history can never be replaced. Now, the Casino dell’Aurora is on the line, in spite of the work that has been put in to save it— why should it too be forgotten?

Isobel Ali is a recent (2022) graduate of the School of Arts & Sciences, Rutgers University, with a BA in Ancient History and Criminal Justice. As a 2022 summer intern, she hopes to see the Villa Ludovisi officially made an historical site in the coming years, and she conveys her deepest thanks to both HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi and Dr. T. Corey Brennan for the unparalleled opportunity to work with this historical material.