By Melis Akçakayalıoğlu (St Andrew’s School ’23)

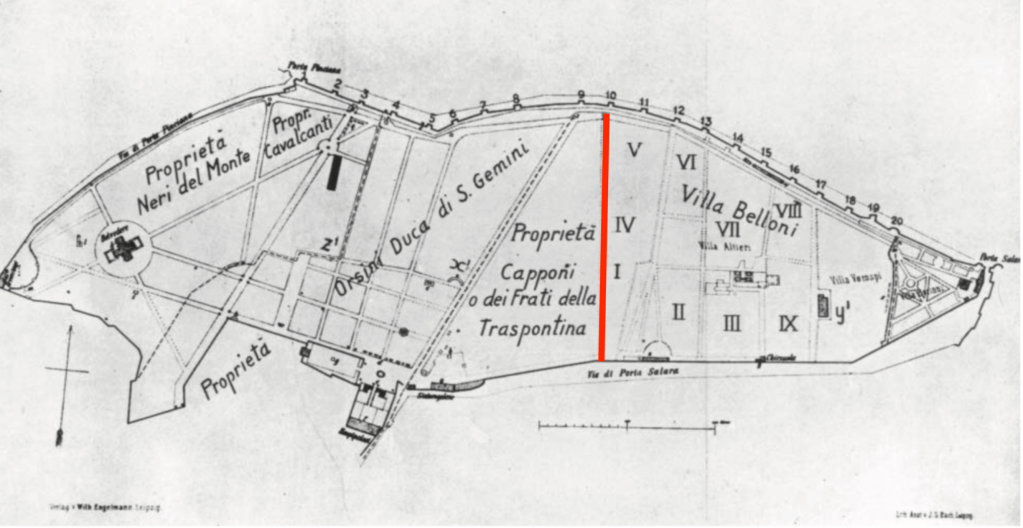

Letter (detail) from Marie Antoinette to Cardinal Ignazio Boncompagni Ludovisi 31 January 1782, announcing the birth of the Dauphin. Collection †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

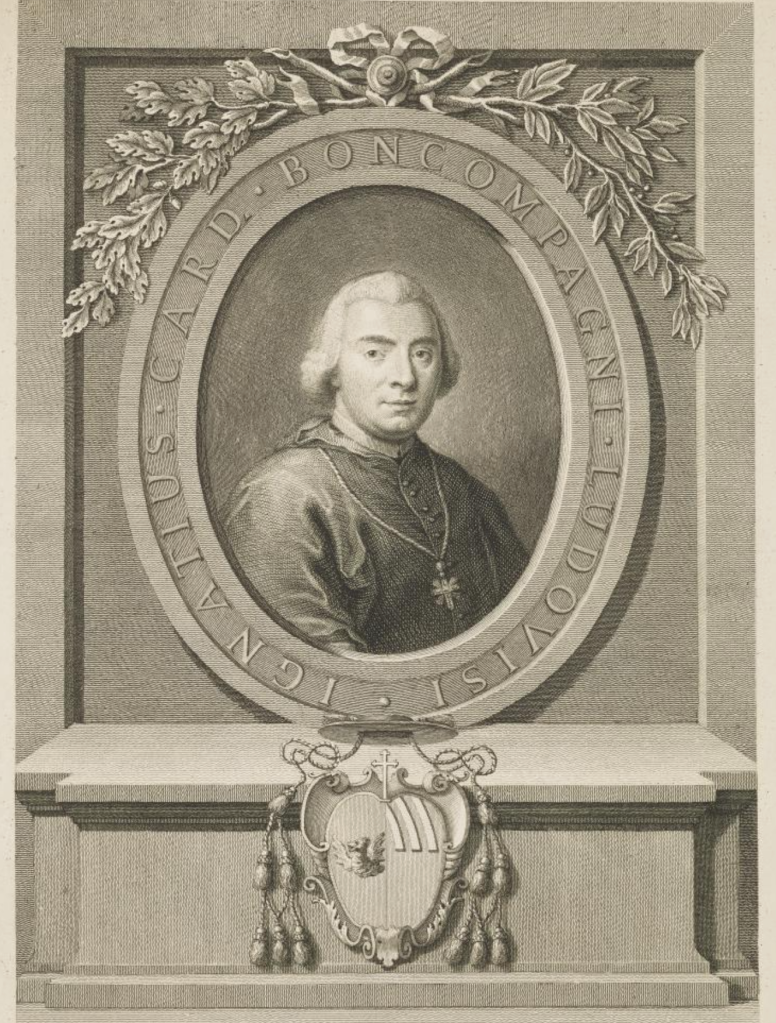

In summer 2010, HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi recovered a large trove of archival documents in a storage area of her home in Rome, the Casino dell’Aurora. These included a total of 25 letters from the years 1775 through 1787 that either Louis XVI (1754-1793) or Marie Antoinette (1755-1793) of France had sent to Cardinal Ignazio Boncompagni Ludovisi (1743-1790).

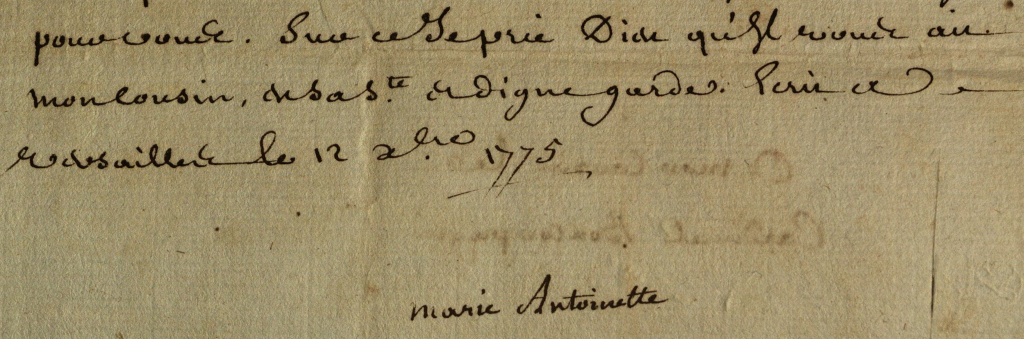

The couple had married on 19 April 1770 and come to the French throne on 10 May 1774. Their 1775 letters, each dated 12 December of that year, congratulate Ignazio Boncompagni Ludovisi on his appointment as Cardinal, which had been announced the previous month, on the 13th of November. The letter of Marie Antoinette shows that the Cardinal wrote to her sharing the news shortly afterwards, on the 15th of November.

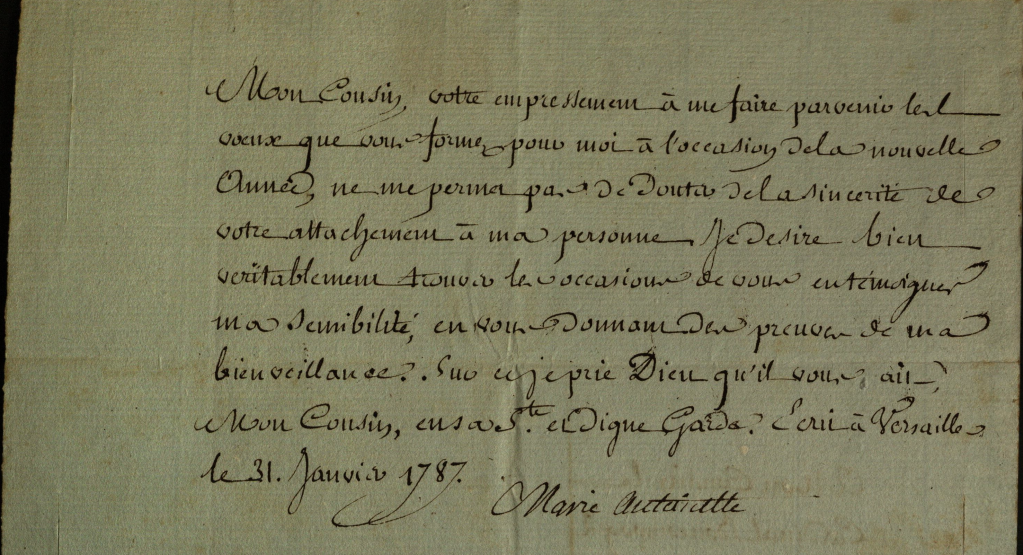

Other than 1775, the rest of the letters are responses to the Cardinal’s New Year’s wishes. For 1776, there is a single letter dated 31 January from the King to the Cardinal, written from the palace at Versailles. For each of the other years in the series, there are messages from both Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette at Versailles.

All but two of those royal letters bear the same calendar date, namely 31 January, considered the last day on which one could properly acknowledge New Year’s greetings. The exceptions are 1779, when the Queen responds on 30 January, and 1787, when the King answers on 28 February, evidently annoyed at the Cardinal’s moving up the date of his annual New Year’s letter to get a quicker acknowledgement.

Portrait by unknown artist of Cardinal Ignazio Boncompagni Ludovisi (1743-1775-1790) holding a letter. Collection †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

The monarchs’ letters have very little personal content, except for those of 1782, which I discuss below. Interestingly, in all these letters Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette each refer to the Cardinal as “Mon Cousin,” revealing how royalty from sovereign states were expected to communicate with one another and betraying the imagined connection underlying royal lines. The Cardinal was from the line of the Princes of Piombino, since 1594 a principality within the Holy Roman Empire, and himself used the title “Principe Cardinale”. In these letters, Cardinal Ignazio clearly takes on significance as royalty for Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette as evidenced by this use of “Cousin.”

These letters of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette mention little in terms of significant familial or personal developments. This fact and the consistent dating seem to imply that Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette merely communicated with the Cardinal out of detached respect and obligation, not true concern.

The two letters in the Vatican Apostolic Archive from the French court to this Cardinal reinforce this impression. When Pope Pius VI appointed Ignazio Boncompagni Ludovisi on 19 June 1785 as Vatican Secretary of State, Louis XVI and his foreign secretary the Comte de Vergennes each wrote to the Cardinal in congratulations on this promotion on 20 September 1785, three months after the announcement and later than any other European rulers (ASV Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi Prot. 10 No. 21 ff. 429-437; I owe this reference to Professor T. Corey Brennan).

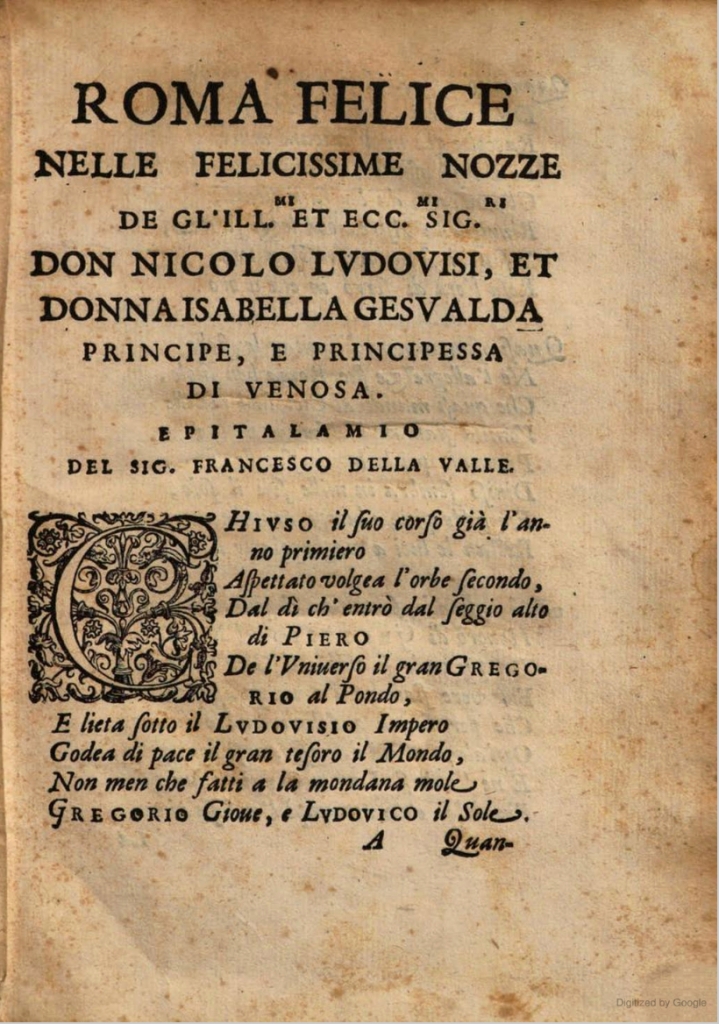

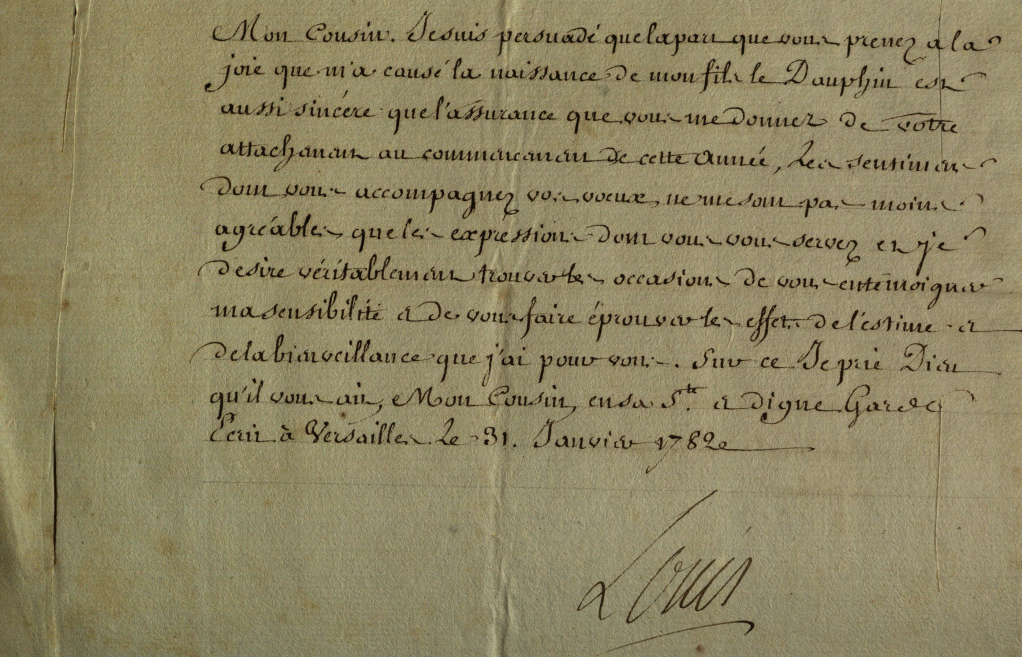

However one pair of letters stands out in the long series from the Casino dell’Aurora archive, both written on 31 January 1782, which mention the birth of the Dauphin (i.e., heir apparent), Louis Joseph, born 22 October 1781. Here are my transcriptions of the letters of the King and Queen. First, Louis XVI:

Letter from Louis XVI to Cardinal Ignazio Boncompagni Ludovisi 31 January 1782, announcing the birth of the Dauphin. Collection †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Mon Cousin, Je suis persuadé que la part que vous prenez a la joie que m’a causé la naissance de mon fils le Dauphin est aussi sincère que l’assurance que vous me donnez de votre attachement au commencement de cette année. Les sentiments donc vous accompagnez vos voeux, ne me sont pas moins agréable que les expressions donc vous vous servez et je desire véritablement trouver occasions de vous témoigner ma sensibilité et de vous faire éprouvou les effets de l’estime et de la bienveillance que j’ai pour vous. Sur ce Je prie Dieu qu’il vous ait, Mon Cousin, en sa sainte digne Grâce. Écrit à Versailles le 31 Janvier 1782. Louis.

“My Cousin, I am convinced that the part that you take in the joy that the birth of my son, the Dauphin, has given to me is as sincere as the assurance you gave me of your attachment at the beginning of this year. The feelings with which you accompany your wishes are no less pleasant for me than the expressions which you use. And I truly desire to find opportunities to show you my predisposition to make you feel the effects of the esteem and benevolence that I have for you. Whereupon I pray to God that he hold you, Cousin, in his holy worthy Grace. Written at Versailles on 31 January 1782. Louis.” [Countersigned by his secretary Charles Gravier de Vergennes]

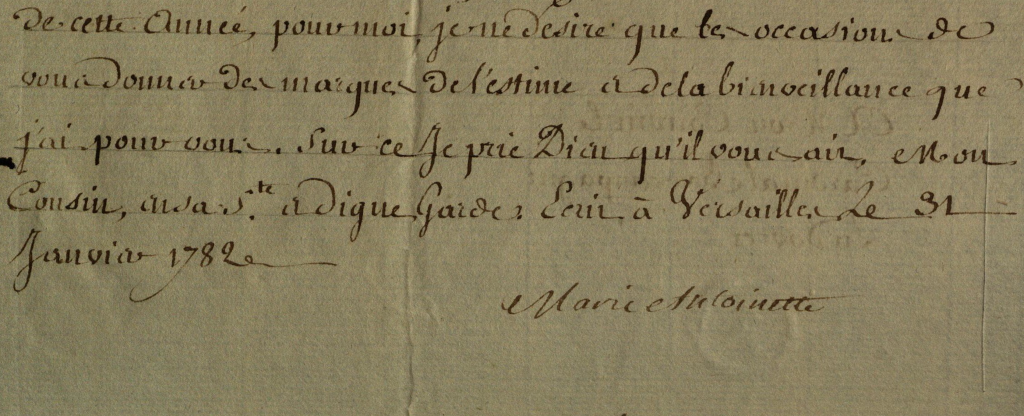

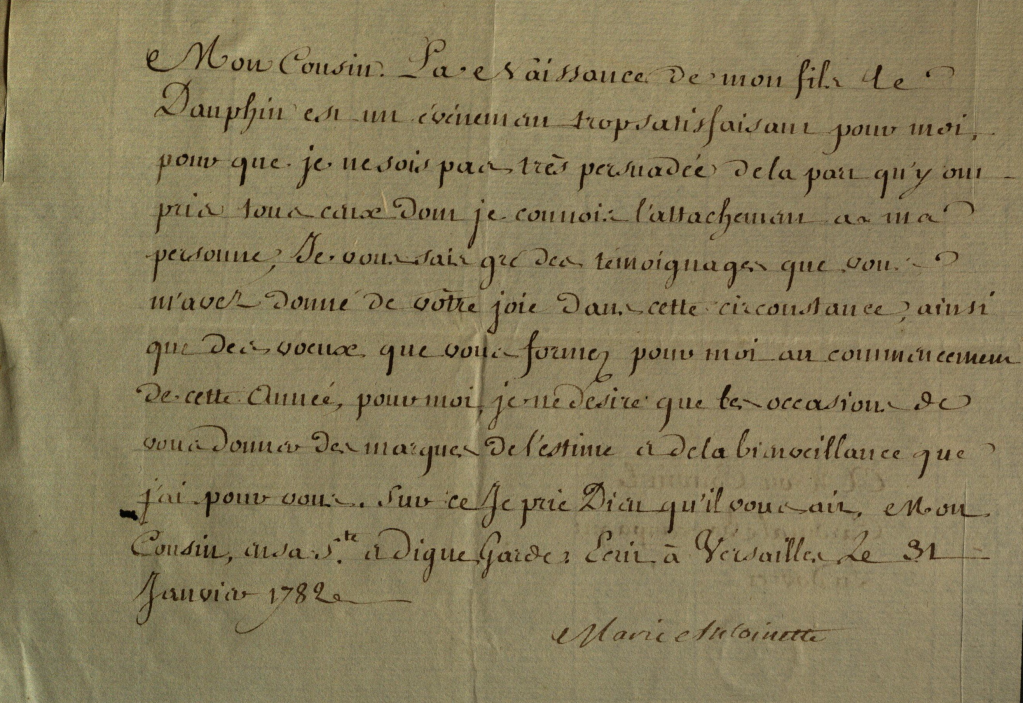

Then Marie Antoinette:

Letter from Marie Antoinette to Cardinal Ignazio Boncompagni Ludovisi 31 January 1782, announcing the birth of the Dauphin. Collection †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Mon Cousin, La naissance de mon fils le Dauphin, est un évenément trop satisfaisant pour moi, pour que je ne sois pas très persuadée de la part qu’y ont pris tous ceux donc je connois l’attachement a ma personne; Je vous sais gré des temoignages que vous m’avez donné de votre joie dans cette circonstance ainsi que des voeux que vous formez pour moi au commencement de cette année, pour moi je ne désire que les occasions de vous donner les marques de l’estime et de la bienveillance que j’ai pour vous. Sur ce Je prie Dieu qu’il vous ait, Mon Cousin, en sa sainte digne Grâce. Écrit à Versailles le 31 Janvier 1782. Marie Antoinette

“My Cousin, The birth of my son, the Dauphin, is for me too satisfying an event for me not to be very convinced of the part played in it by all those whose attachment I know to my person. I am grateful to you for the testimonies that you have given me of your joy in this circumstance as well as for the wishes that you express for me at the beginning of this year. For my part I only desire the opportunities to give you marks of (my) esteem and the kindness I have for you. Whereupon I pray to God that he hold you, Cousin, in his holy worthy Grace. Written at Versailles on January 31, 1782. Marie Antoinette.” [Countersigned by her secretary Nicolas-Joseph Beaugeard]

Significantly, there are no letters by Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette to Cardinal Ignazio Boncompagni Ludovisi that mention the French royals’ other two children. The first was a daughter, Marie-Thérèse, born 19 December 1778. She is not found in the King’s 31 January 1779 or the Queen’s 30 January 1779 letters, though she was born just six weeks before. And after the Dauphin in 1782, there was a second son: Louis Charles, born 27 March 1785 (the future Louis XVII), who is not mentioned in the January 1786 letters.

Video showing how the 1782 Marie Antoinette letter to Cardinal Ignazio Boncompagni Ludovisi was folded, locked and sealed before sending. From Jana Dambrogio (MIT, ADBL board member) and the Unlocking History Research Group: “Marie Antoinette’s Letter with a Removable Paper Lock, France (1782),” Letterlocking Instructional Videos. Unlocking History number 0012/Letterlocking. Filmed Jun 2014.

The Dauphin’s birth is a crucial development because it meant that a male heir has been born. This was a particularly long-awaited event for Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, who did not produce any children for the first eight years after their marriage in 1770, in the face of growing tension within their family and from the public. The attitude that female children and subsequent males are of lesser importance is clearly demonstrated by the fact that these children’s births were not worthy of mention in the letters. These silences also suggest that overall the letters to the Cardinal were tightly focused on their royalty connection.

As it happened, the Dauphin died in 1789, on the 4th of June, five weeks before the Bastille uprising that spelled the beginning of the end of the French Old Regime. We cannot trace these developments from the Boncompagni Ludovisi archive. By this time the series of letters to the Cardinal had broken off—he seems to have annoyed them so much that the King and Queen did not write to him after 1787—and in any case there was chaos in France, that ultimately brought down the monarchy. Cardinal Ignazio did not live to see much of the revolution in France; he died unexpectedly in August 1790, seeking thermal bath therapy in Tuscany at Bagni di Lucca.

Melis Akçakayalıoğlu, a native of Istanbul, is a senior at St. Andrew’s School in Boca Raton FL where she is enrolled in the International Baccalaureate program. In summer 2022 she was a member of the internship program of the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi. She thanks Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for the opportunity to study the materials in the Casino dell’Aurora archive, as well as Professor T. Corey Brennan (Rutgers University) for his guidance in the internship and suggestions on this article, which he made in consultation with Professor Catriona Seth (Oxford University), though emphasizing that she is not responsible for the views offered here.

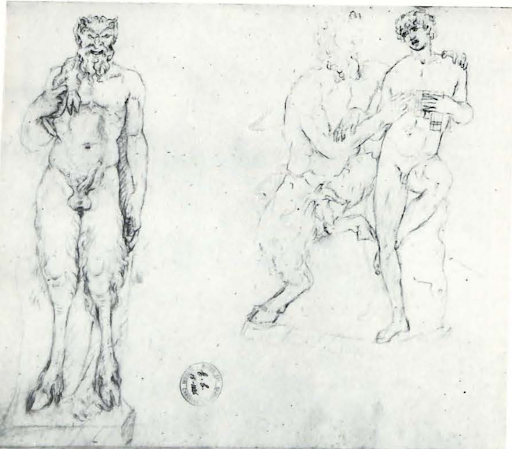

Bronze medal of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette (42mm, 38.99g), commemorating the birth of the Dauphin 22 October 1781, engraved by Pierre-Simon-Benjamin Duvivier. Credit: Bertolami Fine Arts E-Auction 68 Lot 1327 (16 March 2019)