By Meghan O’Keefe-Donohue (Hun School, Princeton NJ)

Detail of ex-Ludovisi bust of Julius Caesar in Museo Nazionale Romano / Palazzo Altemps, inv. 8632. Image: TC Brennan

One of the most notorious attributes of the Ludovisi collection of sculptures in Rome is that the Boncompagni Ludovisi family, especially in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, tightly controlled the manufacture of reproductions of works in their private museum. Casts in plaster were deliberately made scarce.

For instance, in the 1740s, the head of family, Gaetano Boncompagni Ludovisi (Prince of Piombino 1745-1777), allowed the Bolognese Pope Benedict XIV to make some casts, but then broke the molds. Following the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Luigi Boncompagni Ludovisi (Prince of Piombino 1805-1841) sent a few plaster casts abroad in thanks for diplomatic support. But a decade later when Charles X of France wrote to ask him for one, he abrasively denied permission to the king, writing his response on the back of the envelope he had received.

Bronze medal (1932) by Austrian artist Theodor Stundl, commemorating the 100th anniversary of Goethe’s death. It shows the poet contemplating his plaster cast of the Juno Ludovisi. Image: Auktionhaus H. D. Rauch, E-Auction 28 (13 Sep 2018), Lot 1113

Famously, in January 1787 the young Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) was able to obtain two casts of the Juno Ludovisi. “She was my first love in Rome, and now I own her”, he wrote at the time. But it must be remembered that in the Villa Ludovisi before ca. 1800 the colossal Juno head was displayed in open air, near the front gate, and did not have the reputation it does now as one of the top treasures of the collection. Indeed, Goethe himself did much to make the case for this Juno’s masterpiece status.

The year 1841 marks a turning point in general for the Ludovisi collection, with the accession of Antonio (III) Boncompagni Ludovisi as Prince of Piombino. He instituted a ticket system for visiting the family museum. And he also proved much more permissive than his father Luigi in allowing the casting of reproductions.

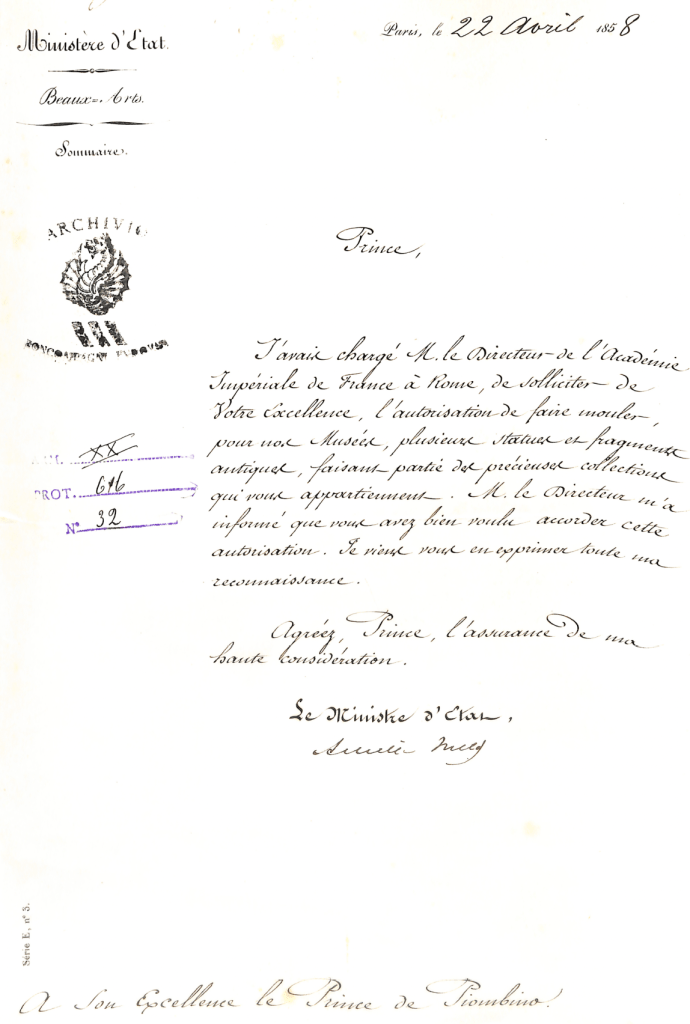

Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi Prot. 616 no. 32: letter (22 April 1858) of French Minister of State Achille Fould to Antonio (III) Boncompagni Ludovisi regarding making copies of sculptures in his private museum. Collection of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

A pair of unpublished letters in the Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi in the Casino dell’Aurora dating to 1858 captures Prince Antonio’s relaxed exchange on the matter of casts with Achille Fould, Minister of State (and Fine Arts) in the cabinet of France’s last emperor, Napoleon III (reigned 1852-1870). Writing from Paris on 22 April 1858, Fould says (my transcriptions and translations):

“Prince, I have charged the Director of the Imperial Academy of France in Rome to ask your highness permission to reproduce several antique statues and pieces from your precious collection for our museums. The Director has informed me that you have grated authorization. I would like to express my sincere appreciation. Please accept the assurances of my highest esteem”, [signed] Achille Fould

Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi Prot. 616 no. 32: reply (1 May 1858) of Antonio (III) Boncompagni Ludovisi to French Minister of State Achille Fould. Collection of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Prince Antonio Boncompagni Ludovisi replies a week later, probably immediately after receiving the letter. Writing from Rome on 1 May 1858, he tells the Minister:

“You have attached far too much importance to the small service I was able to render to museums in peril and, at your recommendation, by granting permission to the Director of the French Academy, to make reproductions of any statues and pieces from my modest collection that please him. Dear Minister, please accept my sincere thanks for your gratitude, Kindest regards,” [Antonio Boncompagni Ludovisi]

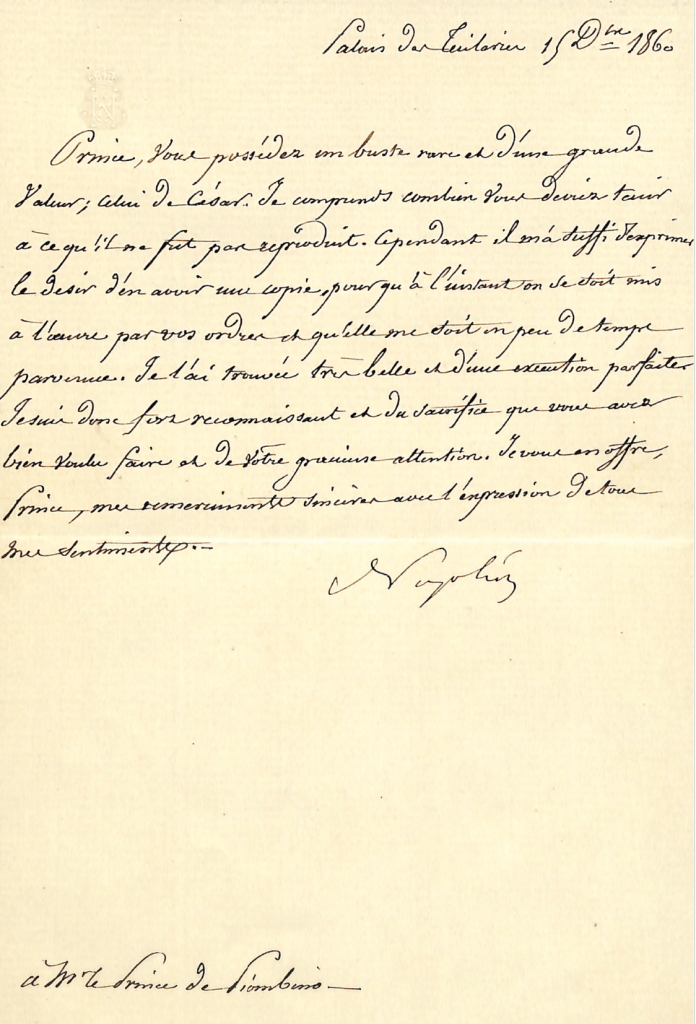

Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi Prot. 590 no. 73: letter in hand of Napoleon III (15 December 1860) to Antonio (III) Boncompagni Ludovisi, regarding making a copy of the Caesar bust. Collection of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Two and a half years later, on 15 December 1860, we find in the Archive a much more specific request. It is to make a plaster cast of a famed portrait bust of Julius Caesar, for which rights of reproduction apparently were reserved. The sculpture in question was completely integral and made of a striking combination of materials, with its its head and neck in bronze, and cloak in red limestone. The letter is sent from Paris’ imposing Tuileries Palace, by the Emperor of France himself, Napoleon III, writing in his own hand. Again, my transcription and translation:

“Prince, you possess a rare and valuable bust; that of Caesar. I understand how much you wished that it not be reproduced. However, it sufficed that I express the desire to have a copy and by your orders, work was immediately started and it reached me a short time later. I found it beautiful and a flawless execution. I am therefore very grateful for the sacrifice you were kind enough to make and for your gracious attentiveness. Please accept, Prince, my sincere thanks and kindest regards, Napoléon”

Napoleon III, 20 francs (gold), 1860. Image: Emporium Hamburg, Auction 85 (8 May 2019), Lot 830.

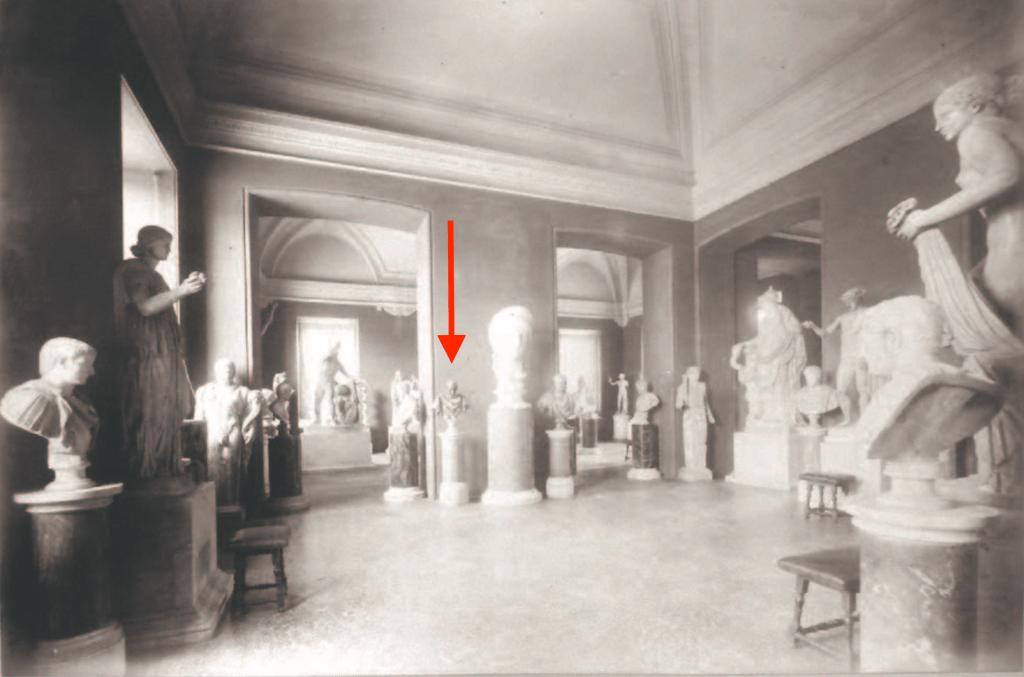

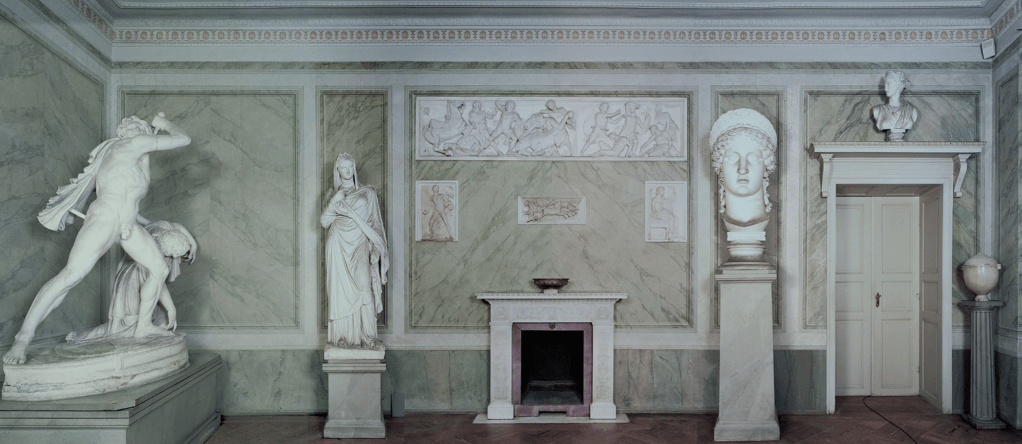

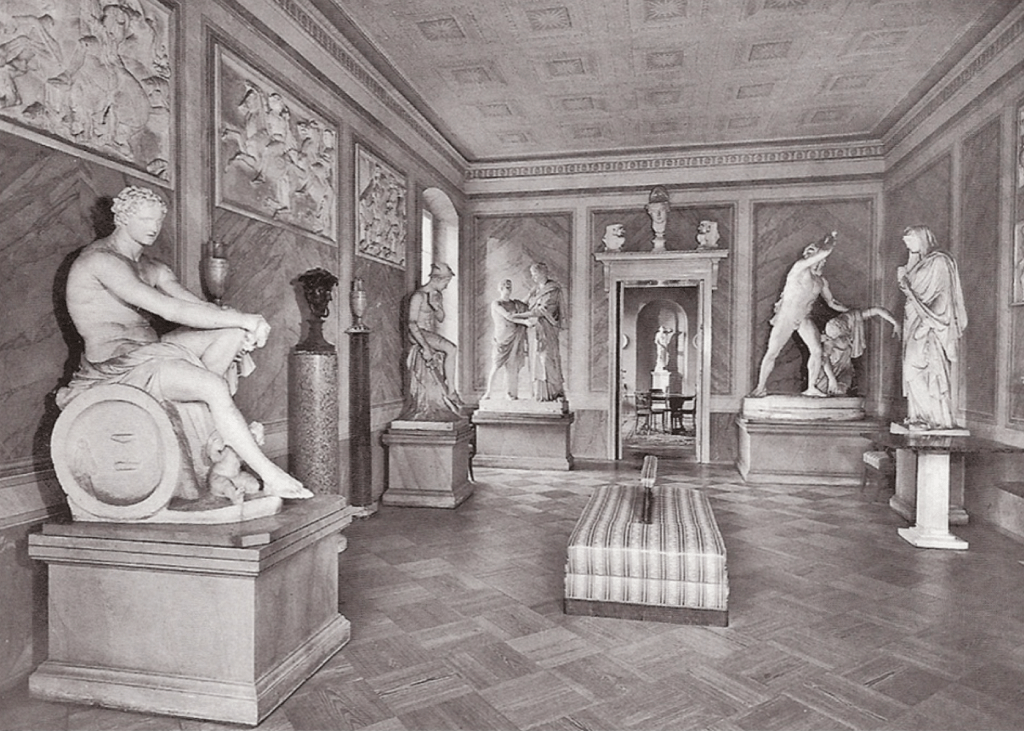

In this case we do not have Prince Antonio’s reply. But it certainly was in the affirmative. By a remarkable stroke of luck, we have photographic images of the interior of the Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi from around the year 1860, i.e., the very time of this exchange. Photos of the south wall of Room II of the family museum, where the Caesar bust was exhibited, shows the series of sculptures with contemporary inventory numbers II 24, 25, 26, 28, 29, 30 and 31. Where is inv. no. II 27, the Caesar bust? It is reasonable to conclude that it is missing because they are making a plaster cast for Napoleon III.

Two views (by the Naples firm of Grillet, ca. 1860) of Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi Sala II. Upper photo (collection of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome): S wall, from left: (behind shutter) bearded Greek head [inv. II 24]; female head [inv. II 25]; Dionysus [inv. II 26]; suiciding Gaul and his wife [inv. II 28]. Lower photo (credit Kallimages): S and W walls, from left: Dionysus (hand) [inv. II 26]; Gaul group [inv. II 28]; bearded Greek portrait [inv. II 29]; Hermes Logios [inv. II 30]; partial views of two uncertain sculptures. Then W wall: Juno Ludovisi [inv. II 41]; relief of Judgment of Paris [inv. II 42]; Bernini’s Rape of Persephone [inv. II 43]. Missing from both views: our bust of Julius Caesar [inv. II 27].

The Julius Caesar bust certainly was back in place when the archaeologist Theodor Schreiber visited the Museum in 1878 to make his definitive catalogue of the ancient components of the sculptural collection. When the Boncompagni Ludovisi in 1890 moved their sculptures to the new Palazzo Piombino on Via Veneto, they placed the Caesar next to the Juno Ludovisi. In 1901, the Italian state purchased the Caesar (and ca. 100 other sculptures from the family’s collection) for the Museo Nazionale Romano, to which it belongs today (inv. 8632, since 1997 at Palazzo Altemps).

The final version of the Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi, in the Palazzo Piombino on Via Veneto, ca. 1890. The bust of Julius Caesar can be seen to the left of the Juno Ludovisi. Image: collection of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

So what precisely is the story of this striking sculpture? Is it even ancient? On this, the fullest discussion is that of Lucilla de Lachenal, in B. Palma and L. de Lachenal (edds.), Museo Nazionale Romano, Le Sculture, I,5: I Marmi Ludovisi nel Museo Nazionale Romano (Rome 1983). I summarize her main points here.

De Lachenal notes that the origin of the Ludovisi Caesar bust is from the Cesi collection, purchased by the Villa Ludovisi’s founder Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi in 1622. She also contends that in 1709 Francesco Ficoroni was the first to suggest that the Caesar bust was modern, drawing comparisons with fifteenth and sixteenth century works such as Donatello‘s Gattamelata or Prophets, and Daniele da Volterra’s portrait of Michelangelo. Scholars who agree with this theory include R. Carpenter, F. Johansen, P. Arndt, and H. von Heintze.

The bust of Julius Caesar, photographed by the Anderson firm in the final version of the Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi, in the Palazzo Piombino on Via Veneto, ca. 1890. From the family’s own album of collection highlights, with notation at bottom: “Julius Caesar, Roman art, end of the Republic”. This shows that the family regarded the bust as ancient. Image: collection of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

De Lachenal continues that scholars who are proponents of the Caesar bust’s authenticity as an ancient work include Theodor Schreiber (1880), J. J. Bernoulli (1882), H. Dütschke (1874-1882), and most notably B. Schweitzer (1948). Schweitzer’s theory contends that it likely was a copy made in late first or second century CE from a late Republican prototype (between 30 and 40 BCE). A date in the era of Nerva or Trajan, it is argued, would account for the combination of a Baroque and “classicizing” stylistic type to create the original elements we find embodied in the Ludovisi Caesar bust.

As it happens, there is a strikingly similar Caesar bust at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. De Lanchenal points out that it too is possibly of modern origin. The busts are so similar in fact, that G. A. Mansuelli (1958) argues that the Florence Caesar could be considered a replica of our Ludovisi piece. Also relevant is a Renaissance-era Caesar, though with cuirass, at the Palazzo Ducale in Mantua. On the other hand, B. M. Felletti Maj, though believing that the Florence Caesar was of modern origin, notes several artworks certainly from antiquity which compare to the Ludovisi Caesar bust. These include the marble portrait of Julius Caesar in Rome at the Palazzo Casali, the Sala degli Imperatori at the Capitoline Museum, one in the Vatican at the Sala a Croce Greca in the Vatican, and the head of an unknown virile figure in the National Roman Museum.

Julius Caesar bust in Museo Nazionale Romano / Palazzo Altemps, inv. 8632. Image: TC Brennan

After surveying these comparisons, De Lanchenal admits that Schweitzer’s theory for the Ludovisi Caesar bust dating to antiquity could be plausible. In support, she cites Mansuelli’s observations that these similar bronze busts of Caesar must originate from a non-metallic archetype—for instance, in basalt—since they lack evidence of inlay or enamel additions on the eyes. (De Lachenal does note that typically it is the other way around: in antiquity, a metal archetype was used to create non-metal pieces.) As an indication of our Caesar’s antiquity, there is also the sculpture’s origins in the Cesi collection, where it was the only bronze in its “Imperial Series”. And so, De Lachenal argues, it was most likely not created for the Cesi to complete the series, as often occurred in collections during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

However De Lachenal concludes that the piece is most likely modern, pointing to the physical structure of the Ludovisi Caesar bust. While underlining that a thorough study of the head’s casting technique and repairs is necessary, she argues on stylistic grounds that the structure of the head with a small round skull and narrow temples, strong but flat chin, sunken wrinkles on the sides of the mouth and forehead, and the hair made up of individual strands with an invisible but exact outline point toward a much different date of origin for the bust: the sixteenth century.

In the Museo Nazionale Romano / Palazzo Altemps, the catalogue and exhibition label add that the red limestone of Caesar’s cloak can be traced to the Kotor region, on the eastern Adriatic coast in Montenegro. This stone was imported by the Republic of Venice, and mainly used in the northeastern part of the Italian peninsula. This in turn suggests at least the lower portion of the bust’s manufacture in a workshop of northern Italy—perhaps Mantua, in the sixteenth century.

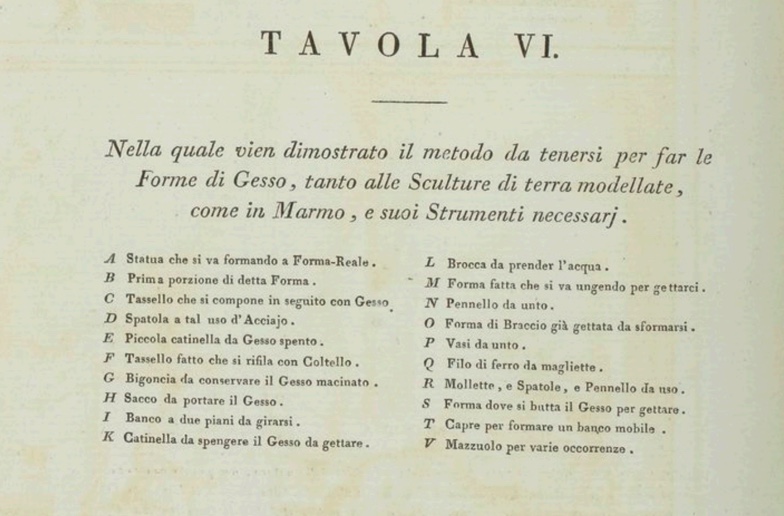

From Francesco Carradori, Istruzione elementare per gli studiosi della scultura (Florence 1802), illustrating the process for making plaster casts of sculptures, and the many tools required. Image: Google Books.

So how were casts made? First, the castmakers study the sculpture and its form. Generally the more limbs and hollow spaces there are, the more difficult it will be to create a cast. Next—very important—the sculpture is coated in a release agent so the plaster will not stick to it. A non-drying clay is placed in a support and used to create walls around individual pieces of the sculpture.

Then the plaster powder is mixed with water and poured into each section contained by the walls of the non drying clay. Once the plaster has set, the clay walls and plaster pieces are removed and the piece is smoothed and trimmed. Now each piece should fit together like pieces of a puzzle. As stated before, limbs are the most difficult part of the process and several moulds separate from the rest of the sculpture body must be made. The previous steps are repeated for each individual section of the sculpture created by the clay walls.

Then a “jacket” of plaster is made with each piece; special fabric strips and wet plaster hold all sections in place. When this ‘jacket’ is set, it is cut open and removed from the cast pieces. Each section is then carefully removed from the original sculpture and placed back into the corresponding spaces in the “jacket”. The two sides of the “jacket” are strapped together and plaster is poured into the mould, and the whole mould with the plaster inside is then rocked back and forth to ensure all of the plaster gets into every crevice.

Once the plaster has set, the “jacket” is opened and each section of the plaster mould is removed. If there are limbs, they have to be separately attached to the completed figure with screws. One can notice that in some casts slight lines may appear where joints, limbs, or large sections are attached separately. All this means the casting process was extremely difficult.

Survey photograph of the north wall of the Antiquities Gallery, Tegel Castle, Berlin, showing casts of Ludovisi sculptures acquired by Alexander von Humboldt in 1819. Image: Martina Abri

Fortunately, the Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi contains some records of cast making, indicating the time and expense involved. The fullest account may be from the years 1817-1820 (Prot. 614, nos. 113 and 115, today in the Vatican Apostolic Archive), when Prince Luigi Boncompagni Ludovisi was especially focused on rewarding allies who had supported his claims to the Principality of Piombino at the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

Four famed works were chosen for reproduction: the Suicidal Gaul group (then called “Arria and Paetus”); the Electra and Orestes group (“Lucius Papirius and his mother”); the seated Mars; and the Juno Ludovisi. A castmaker named Vincenzo Malpieri receives a total of 870 scudi (in installments) to create casts of the two groups, and 315 scudi (also in installments) for the Mars and the Juno. The difference in price confirms what we would already suspect, that the groups were more complicated. It takes almost three full years for Malpieri to complete his work.

Survey photograph of the west wall of the Antiquities Gallery, Tegel Castle, Berlin, showing casts of Ludovisi sculptures acquired by Alexander von Humboldt in 1819. Image: Martina Abri

When the casts of the four works were ready in June 1819, Prince Luigi distributed them as follows. To reward the Austrian diplomat Prince Metternich, the Imperial Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna received copies of all four. So did Baron Alexander von Humboldt, as well as Ferdinand III, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. George IV, the Prince Regent of Great Britain, was gifted with the two groups. And Lord Burghersh, the British Plenipotentiary in Florence, received a cast of the seated Mars Ludovisi.

A final question. Why was Napoleon III in 1860 so eager to have specifically the Ludovisi bust of Julius Caesar? Napoleon III’s obsession with Julius Caesar has been well noted, and in 1865 he published his own History of Julius Caesar. He interpreted the historical narrative of Julius Caesar to disseminate his own agenda to a world audience. Napoleon III’s History of Julius Caesar justified his own power, his ambitions for France, and his imperial intent. The Ludovisi Caesar bust represented these ideas visually to Napoleon III, which explains his desire for the cast to be made.

Napoleon III, Histoire de Jules César (Paris: Henri Plon, 1865-1866), in two volumes with Atlas. Image: BiblioAntiques (Vendoeuvres FR)

Meghan O’Keefe-Donohue is a Teaching Fellow at the Hun School Of Princeton, and currently teaches Latin. Meghan graduated magna cum laude from Rutgers University in 2023, majoring in Classics with a double minor in Archaeology and Italian. She studied abroad in Rome for a year where she was able to study classics and Italian, which greatly assisted in writing this piece. She was even able to visit some of the pieces mentioned above in person, including the Caesar bust at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, and the Caesar Ludovisi bust itself in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Altemps. She thanks Professor Brennan for his support, guidance, and encouragement over the course of this project. She is eternally grateful for his continued mentorship. She also extends her deep gratitude to HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for the access to the exceptional private family archive and the opportunity to work on this historical material.

Postcard (1935) showing Antiquities Gallery, Tegel Castle, Berlin, with casts of seated Mars Ludovisi (left), Electra and Orestes (left of door), and Suicidal Gaul (right of door). A cast of the Juno Ludovisi (against right wall, opposite the Mars) is outside the frame. Collection TC Brennan

How can I ever begin to express my gratitude to Meghan O’Keefe Donohue, for her extensive research, on the history of our Julius Caesar statue? As she describes and uncovers the obsession of Napoleon III with our statue, I was transported back to 1860. She brought this historic period to life for me. Additionally, I would like to thank our Nobile Professor Corey Brennan for his stalwart support for my husband and me throughout these many years. Without Professor Brennan, Chancellor Edwards, and Rutgers University thousand of documents might have been stolen or destroyed. Thank you.