By Vinya Lingamneni (Rutgers ’26)

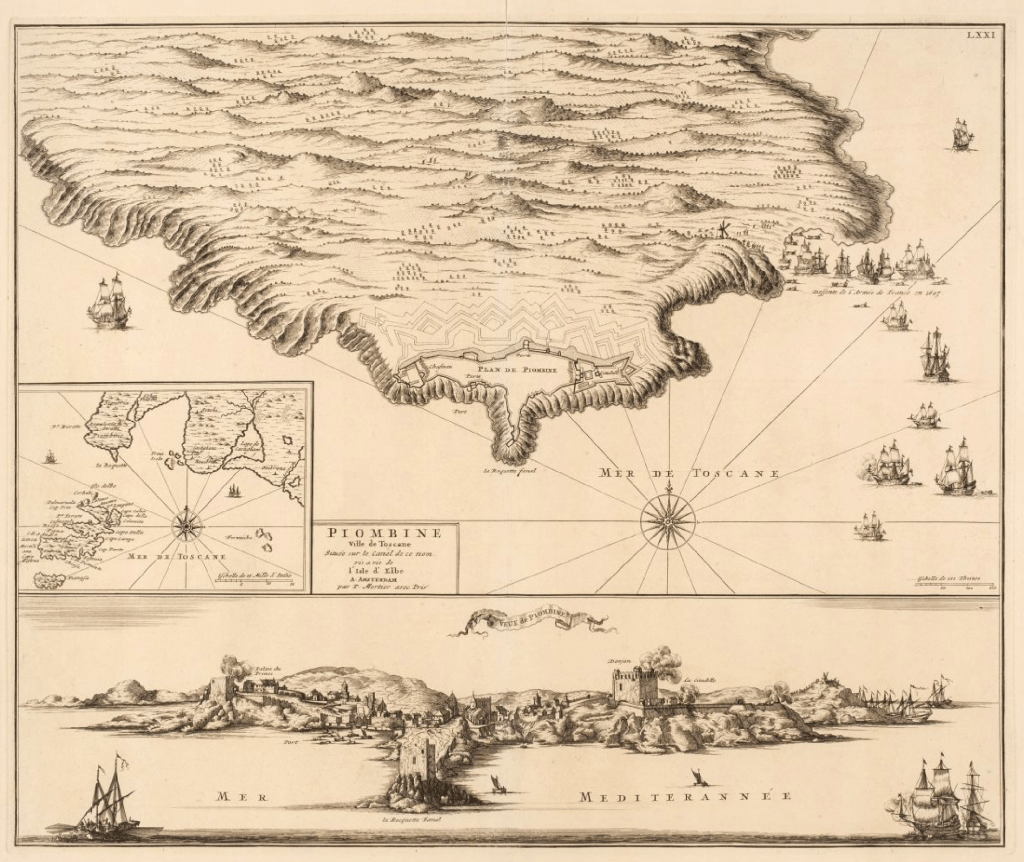

Maps and view of the Principality of Piombino (with its possession the island of Elba), by P. Mortier, Amsterdam ca. 1724 (after J. Blaeu 1705). Credit: Dominic Winter Auctioneers

Olimpia Ippolita (I) Ludovisi held the title of Princess of Piombino from 1700 until her passing in 1733, and ruled the principality as sovereign from 1707. Born in Cagliari (Sardinia) on 24 December 1664, Ippolita was the fourth of five children of Niccolò Ludovisi, nephew of Pope Gregory XV (reigned 1621-1623), who acquired the principate of Piombino in 1634, and Constanza Pamphilj, the Princess of San Martino and Alviano, and niece of Pope Innocent X (reigned 1644-1655). So Ippolita was the grand-niece of two 17th century Popes.

As it happened, Ippolita was to be the last of the Ludovisi. Her father Niccolò died in Sardinia just one day after her first birthday, and her mother Costanza just three months after that, in childbirth with a son who soon died. Her elder brother Giambattista Ludovisi (born 1647), the second Prince of Piombino, died on 24 August 1699, leaving as his only child an infant son who did not live to the end of the year. And Ippolita’s one remaining sibling Olimpia, a nun, died on 27 November 1700.

Gold zecchino (1696) of Piombino, with portrait of Giambattista Ludovisi, elder brother of Ippolita, who ruled as Princ of Piombino 1665-1699. Credit: Sincona

Contemporaries certainly saw clearly the precarity of the Ludovisi family’s future and fortune. On 19 October 1681, aged 17, Ippolita was more or less forcibly married to the 5th duke of Sora and Arce, Gregorio (II) Boncompagni, the great-great-grandson of Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni (ruled 1572-1585), who was 22 years her senior. With this marriage the two Papal families of the Boncompagni and Ludovisi, each originating from Bologna, formally merged into one.

Gregorio Boncompagni and Ippolita Ludovisi were to have seven children in the years 1684-1697, a boy who died aged 2, and six girls. This situation posed a fresh peril for the Ludovisi name. The solution for succession was an extreme one. In 1702, the couple’s eldest daughter, Maria Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi (born 1686), at age 15 married a 43 year old uncle, her father’s younger brother Antonio (I) Boncompagni. And so on the death of Ippolita in 1733, the Principality of Piombino remained in the Boncompagni Ludovisi family. Though just three of her daughter Eleonora’s six children survived to adulthood, it was enough to perpetuate the family which is still thriving today.

Gregorio (I) Boncompagni and his wife Ippolita Ludovisi (B+W reproductions of portraits that today hang in the Casino dell’Aurora). By marriage compact (1681), their descendants would bear the name Boncompagni Ludovisi. Collection of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

The Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi at the Casino dell’Aurora in Rome was uncovered in 2010 by HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi. Among the first documents identified was a set of six letters received from the court of Louis XIV of France, all sent in the months that follow the death of Ippolita’s husband Gregorio. That took place on 1 January 1707 at the Boncompagni estate of Isola del Liri in southern Lazio. These letters rather specifically shed light on the relationship between the Prince and Princess of Piombino on the one hand, and the Sun King and the French royal family on the other.

Both the Boncompagni and the Ludovisi families were conspicuous supporters of France against Spain, and so it is notable that these documents, all warm exchanges, exist at all. The letters show an amiable disposition between the French royal family and the Boncompagni Ludovisi couple. The letters use “Cousin” and “Friend” as a greeting, even though there is no family relationship between the two parties. “Cousin” was a traditional way that European sovereigns would greet each other at this time. Furthermore, all but one of the letters lack a countersign from a secretary, signifying a trustworthy relationship. (The exception is the one letter from Louis XIV, countersigned by his foreign secretary Jean-Baptiste Colbert de Torcy.)

Silver ecu of France (1647) commemorating the French capture of Porto Longone on Elba (marked ILVA on the coin’s reverse), part of the Principality of Piombino, in 1646. Credit: iNumis

It would be a long story to detail the dealings of the Ludovisi and Boncompagni with the French court in the 17th and early 18th centuries. In short, the principality of Piombino—which encompassed also the island of Elba, and its militarily important harbor of Porto Longone—was a cause of conflict in the 1640s through 1670s between the French and the Ludovisi princes. However, in the mid-1680s agents of Louis XIV seriously entertained buying the Villa Ludovisi and its fabled collection of antique sculptures, perhaps to house the French Academy in Rome. French relations with the Boncompagni were less vexed, as routine royal correspondence shows, starting in 1658 under Louis XIII.

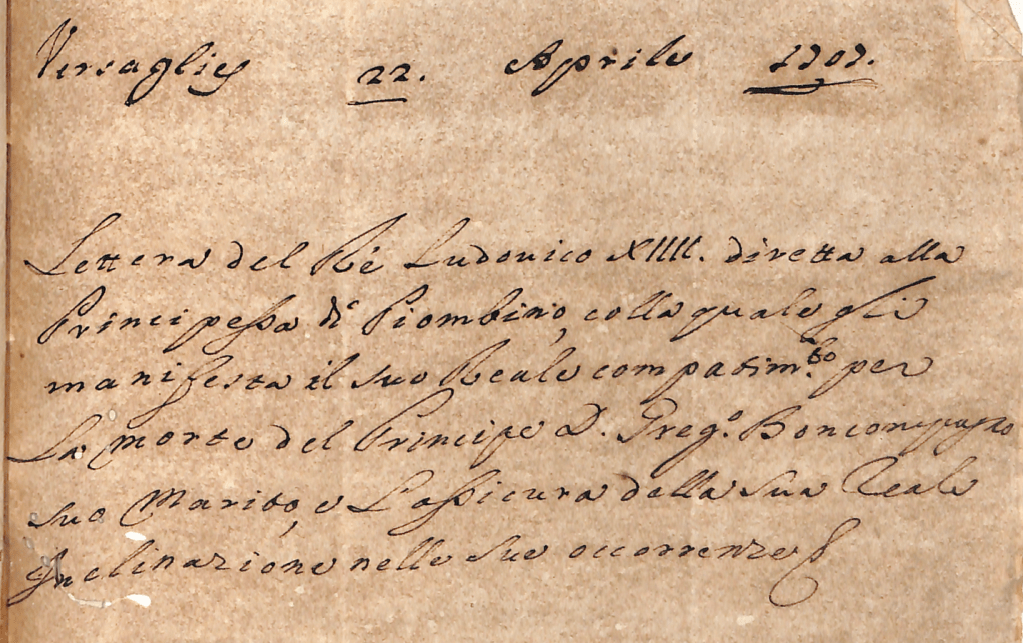

Boncompagni Ludovisi archivist’s note (18th century?) accompanying 22 April 1707 letter of Louis, the Grand Dauphin, to Ippolita Ludovisi—misidentifying the sender as king Louis XIV himself.

This is all necessary background for the set of six letters sent from the French court to Ippolita Ludovisi in winter and spring of 1707. They are genuinely confusing, to the extent that even the Boncompagni Ludovisi family archivists of the late 18thcentury get things wrong, not realizing that multiple generations of the French royal family were communicating with the lords of Piombino.

In essence, the six letters as a whole concern the death in Italy on 1 January 1707 of Gregorio Boncompagni, and the birth at Versailles on 8 January 1707 of Louis, the second Duke of Brittany. The parents in question are Louis, Petit Dauphin, the Duke of Burgandy (grandson of king Louis XIII) and his wife Marie-Adélaïde of Savoy. Their first child, the first Duke of Brittany, had died in infancy in 1705. Unfortunately, the new Duke of Brittany would die of measles in 1712, and his parents sadly both died the same year.

Silver medal dated 1707 from Duchy of Burgundy, commemorating Marie-Adélaïde of Savoy. The reverse, showing a sprouting olive tree with the Latin legend SPES NOVA (“fresh hope”), should refer to the birth of her son the Duke of Brittany in January of that year. Credit: iNumis

Five of the six letters are addressed to the Princess of Piombino, Ippolita Ludovisi. But the last of the set, dated 1 May 1707, is addressed to the Prince of Piombino, Gregorio Boncompagni, even though he died a full four months previously. And of these six letters from Versailles, there are four different correspondents, three of them named Louis. There is the king Louis XIV, the longest reigning monarch in all of history, who held France in the forefront as a world power. Then his son and heir the Grand Dauphin, and the king’s grandson the Petit Dauphin, second in line for the throne. The fourth correspondent is the wife of the Petit Dauphin, Marie-Adélaïde.

At this point two charts may be useful (the correspondents are marked in bold):

Louis XIV (1707), “double Louis d’or aux insignes” coin. Credit: Leu Numismatik

LETTERS SENT BY THE FRENCH COURT TO THE PRINCIPALITY OF PIOMBINO IN FEBRUARY TO MAY 1707

Content: * = thanks for congratulations on birth of Louis, Duke (II) of Brittany. † = condolences for death of Gregorio Boncompagni, who had died 1 January 1707

(1) 28 February 1707* Marie-Adélaïde to Ippolita Ludovisi

(2) 28 March 1707*† Louis, Petit Dauphin [18th century Boncompagni Ludovisi archivist “Louis XIV”] to Ippolita Ludovisi

(3) 5 April 1707* Marie-Adélaïde to Ippolita Ludovisi

(4) 20 April 1707* Louis, Grand Dauphin [archivist “Louis XIV”] to Ippolita Ludovisi

(5) 22 April 1707† Louis, Grand Dauphin to Ippolita Ludovisi

(6) 1 May 1707* Louis XIV to (deceased) Gregorio Boncompagni

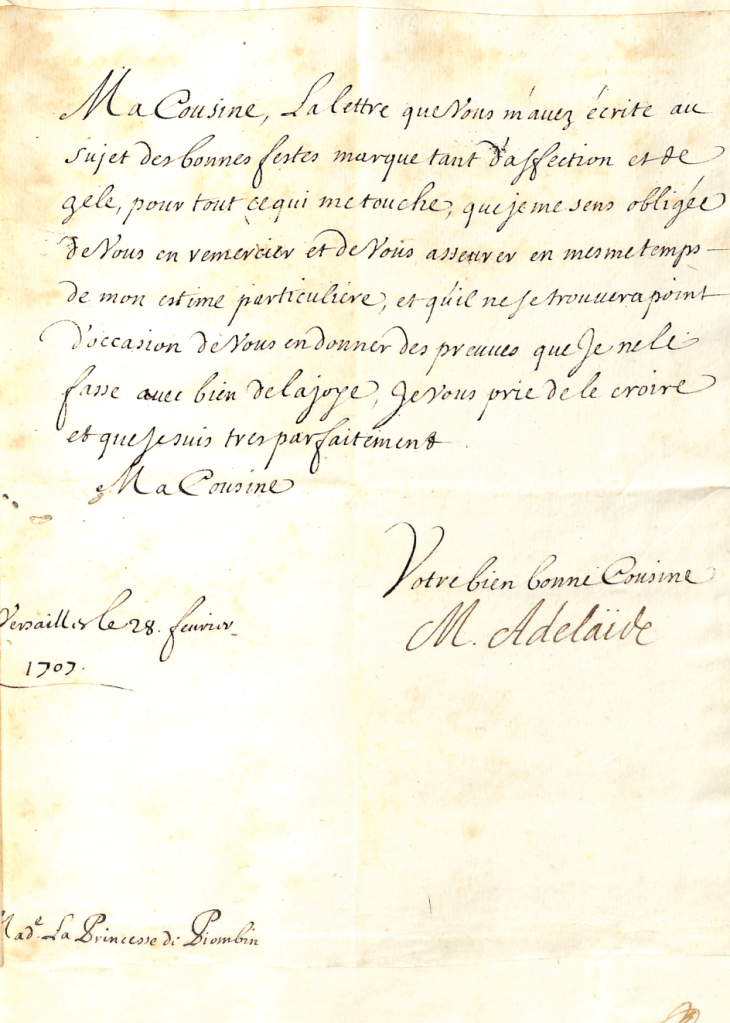

The letters form three sub groups. The first letter in the series is sent 28 February 1707 by the mother of the Duke of Brittany, apparently unaware that Gregorio Boncompagni had passed away a few days before the birth of her son. The second letter comes a month later from the infant Duke’s father, to thank Ippolita for her congratulations on the birth, while offering her condolences on the death of her husband. Then a week after that, on 5 April, there is a third letter from the mother, reiterating her thanks about the birth greetings, but saying nothing about Ippolita’s loss.

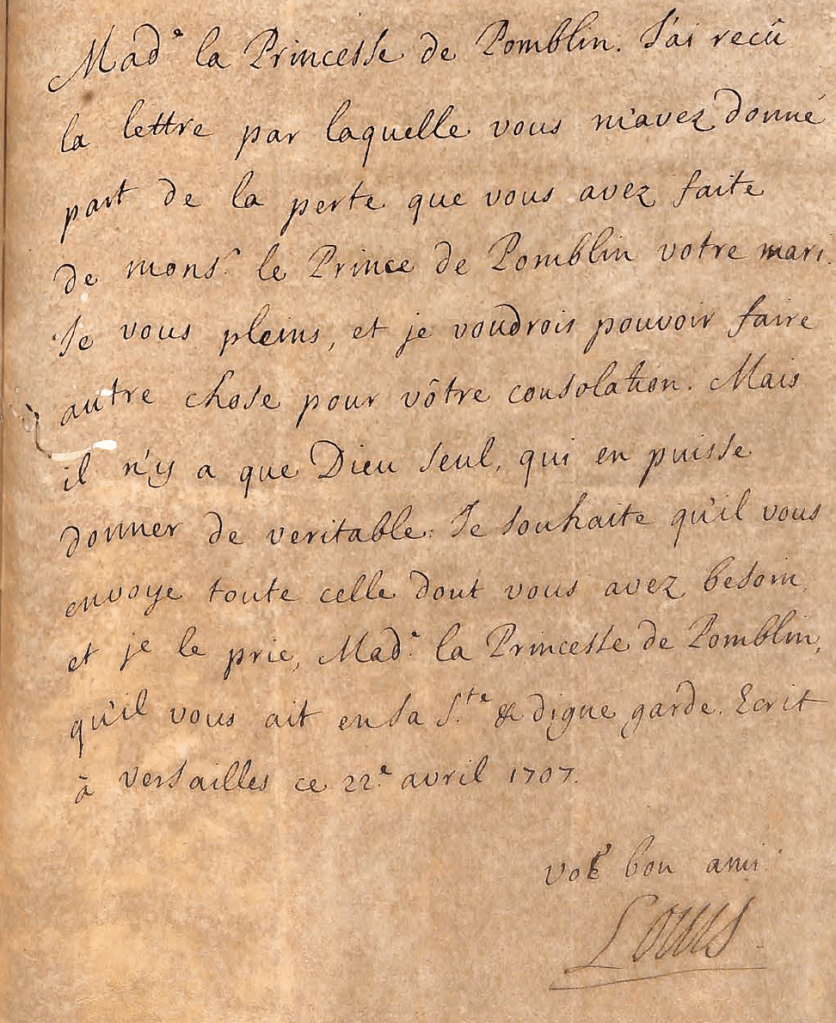

The second sub-group consists of paired letters from the Grand Dauphin, sent just two days apart, on 20 and 22 April 1707. In the first, he thanks Ippolita for wishing his grandson Louis, Duke of Brittany well. A second letter expresses sympathy for the death of Gregorio II Boncompagni. This implies that the Grand Dauphin was unaware of Boncompagni’s death, as he had to write a separate letter to offer condolences rather than keeping both thoughts in one letter. The 28 March letter of his son, the Petit Dauphin, suggests that there was nothing inappropriate about expressing thanks and condolences in the same letter. In other words, we can see the Grand Dauphin here fixing a faux pas.

The third sub-group, a single letter from 1 May, is a real outlier, in which the Sun King thanks Gregorio Boncompagni—now dead a full four months—for congratulations on his great-grandson’s birth. Since Gregorio had died a full week before the birth of the Duke of Brittany, he cannot have written such a letter to Louis XIV.

So in these three letters, we can see some confusion about Gregorio Boncompagni’s death. It is only the Petit Dauphin who seems to have full control of the facts. The Grand Dauphin writes two letters to Ippolita, first thanking her and subsequently expressing grief for her husband’s death. Marie-Adélaïde also writes two letters to Ippolita, but in each misses the chance to offer condolences. Finally, the Sun King addresses his letter directly to Gregorio Boncompagni as if he were still alive, who in any case would never have been able to send a letter on the birth of the second Duke of Brittany. Looking at these cordial letters together as a set reveals some unexpected dynamics between the French court and the Boncompagni Ludovisi, and illuminates not just the difficulties of long-distance communication among sovereigns in the early modern period, but also of communication within Versailles itself.

I. MARIE-ADÉLAÏDE 28 FEBRUARY 1707 TO IPPOLITA LUDOVISI

Ma Cousine,

La lettre que Vous m’avez écrite au sujet des bonnes festes marque tant d’affection et de zele, pour tout cequi me touche, que je me sens obligée de vous en remercier et de Vous assurer en même temps de mon estime particulière, et qu’il ne se trouvera point d’occasion de Vous en donner des preuves que je ne li fasse avec bien de la joye, je Vous prie de le croire est que je suis très parfaitement.

Ma Cousine, Votre bien bonne Cousine, M. Adelaïde, Versailles le 28. Janvier. 1707.

[Addressed to:] Madame la Princesse di Piombin

My Cousin,

The letter you wrote to me regarding the joyful celebrations displays so much affection and zeal for everything that concerns me that I feel obliged to thank you and assure you of my special esteem. There will be no shortage of occasions for me to prove this, and I will do so with great joy. Please believe that I am sincerely

My Cousin, Your very kind Cousin, M. Adelaïde, Versailles, January 28, 1707.

[Addressed to:] Madame the Princess of Piombino

II. LOUIS PETIT DAUPHIN 28 MARCH 1707 TO IPPOLITA LUDOVISI

Ma Cousine,

Vous ne devéz pas douter que je Je suis desolé pas pouvoir que je náye lu avec beaucoup de plaisir la lettre par laquelle vous m’aprenez la perte que vous avez faite je souhaitte fort que les sentiments que jay pour vous et tout cequi vous apartiene, vous puisse etre de quelque consolation, je voir aussy par une seconde lettre que votre affliction ne vous a pas empesché desire sensible a l’heureuse nouvelle de la naissance de mon fils le Duc de Bretagne, je recois comme je dois ces preuves de votre attachement je seray bien aise quand je se presentera des occasions de vous faire connoitre l’estime et la affection particuliere que jay pour vous je suis, a Versailles le 28 mars 1707,

Votre bien bon cousin , Louis

My Cousin,

You should not doubt that I am deeply saddened not to have read with great pleasure the letter in which you informed me of the loss you have suffered. I sincerely hope that the feelings I have for you and everything that belongs to you can provide some consolation. I also see from a second letter that your affliction has not prevented you from being delighted by the happy news of the birth of my son, the Duke of Brittany. I receive these tokens of your attachment as I should, and I will be pleased when opportunities arise to make known to you the esteem and special affection I have for you. I am in Versailles on March 28, 1707.

Your very kind cousin, Louis

III. MARIE-ADÉLAÏDE 5 APRIL 1707 TO IPPOLITA LUDOVISI

Ma Cousine,

Je me suis facilement persuadée que Vous avez reçu avec bien de la joye la nouvelle de l’heureuse naissance de mon fils Le duc de Bretagne. Les temoignages que Vous me donnés en cette occasion de Votre affection, me sont assés connoistre que c’est de bon coeur que Vous y avez pris part, aussi je Vous asseure qu’on ne peut estre plus reconnoissante de toutes Vos honnestetés que je la suis, et que je voudrois trouver lieude Vous marquer mon estime étant veritablement.

Ma Cousine, Votre bien bonne Cousine, M. Adelaïde, Versailles le 5. avril 1707.

My Cousin,

I have easily convinced myself that you received with great joy the news of the happy birth of my son, the Duke of Brittany. The expressions of affection you have shown me on this occasion are enough to make me understand that you genuinely took part in it with a full heart. I assure you that I am most grateful for all your kindnesses, and I wish to find a way to express my esteem to you, being truly

My Cousin, Your very kind Cousin, M. Adelaïde, Versailles, April 5, 1707.

IV. LOUIS DAUPHIN 20 APRIL 1707 TO IPPOLITA LUDOVISI

Madame la Princesse de Pomblin,

Vous m’avés si bien marqué la part que vous prénnés a ce qui me touche, par la joye que vous m’avés témoignée de la naissance de mon petit fils le Duc de Bretagne, que j’ai regardé tout ce que vous me dites la dessus comme autant de marques de votre affection. Je ne saurois mieux vous témoigner quel est le gré que je vous en say. Mais je desire de vous le faire connoistre. Cependant je prie Dieu qu’il vous ait, Mad.e la Princesse de Pomblin, en sa sainte et digne garde. Ecrite à Versailles ce 20. avril 1707

Vostre bon ami, Louis

Madame Princess of Piombino,

You have so clearly shown the part you take in what concerns me by the joy you have expressed about the birth of my grandson, the Duke of Brittany, that I consider everything you tell me on the matter as tokens of your affection. I cannot better show you my gratitude for it. But I wish to make it known to you. Meanwhile, I pray to God that He may have you, Madame la Princesse de Pomblin, in His holy and worthy keeping. Written in Versailles on April 20, 1707

Your good friend, Louis

V. LOUIS DAUPHIN GRAND 22 APRIL 1707 TO IPPOLITA LUDOVISI

Madame la Princesse de Pomblin,

J’ai reçu la lettre par laquelle vous m’avez donné part de la perte que vous avez faite de monsieur le Prince de Pomblin votre mari. Je vous pleins, et je voudrois pouvoir faire autre chose pour vôtre consolation. Mais il n’y a que Dieu seul, qui en puisse donner de veritable. Je souhaite qu’il vous envoye toute celle dont vous avez besoin, et je le prie, Madame la Princesse de Pomblin, qu’il vous ait en sa sainte et digne garde. Ecrit à Versailles ce 22 avril 1707.

Vostre bon ami, Louis

Madame Princess of Piombino,

I have received the letter in which you informed me of the loss of Monsieur le Prince de Pomblin, your husband. I pity you, and I wish I could do something more for your consolation. But only God alone can provide true consolation. I hope He sends you all that you need, and I pray, Madame Princess of Piombino, that He has you in His holy and worthy keeping. Written in Versailles on April 22, 1707.

Your good friend, Louis

VI. LOUIS XIV TO GREGORIO BONCOMPAGNI

A Mon Cousin le Prince Piombin

Mon Cousin,

La lettre que vous m’avez ecrite a l’occasion de la naissance de mon arriere petit fils le Duc de Bretagne, contient de nouveaux temoignages de la sentiment que vous faiter paroitre en toute occasion sur cequi me regarde, et je suis entierement persuadé de la sincerité de la joye que vous avez fait paroitre d’un evenement aussy heureaux dans toutes les circonstances. Vous devez croire que je vous en seay beaucoup degré, et que vous estimant autant que je fair je seray toujours bien aise de vous en donner de remarquer. Sur ce je prie Dieu qu’il vous ayt Mon cousin en sa sainte et digne garde. Ecrit à Versailles ce 1.er jour de May 1707.

Louis

To my cousin the Prince of Piombino

My Cousin,

The letter you wrote to me on the occasion of the birth of my great-grandson, the Duke of Brittany, contains new expressions of the sentiments you always show on everything concerning me, and I am entirely convinced of the sincerity of the joy you displayed on such a happy event in all circumstances.

You must believe that I am deeply grateful, and as I hold you in as high esteem as you do me, I will always be pleased to show it to you. With this, I pray to God to have you, my cousin, in His holy and worthy keeping.

Written in Versailles on the 1st day of May 1707.

Louis

Sources used: Mauro Carrara, Signori e principi di Piombino (Bandecchi & Vivaldi, Pontedera 1996); Philip Mansel, King of the World: The Life of Louis XIV (University of Chicago Press, 2020); John C. Rule and Ben S. Trotter, A world of paper: Louis XIV, Colbert de Torcy, and the Rise of the Information State (McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal and Kingston, 2014 [esp. p168 on official communications regarding the 1707 birth of the 2nd Duke of Brittany]).

Vinya Lingamneni (Rutgers University ’26) is pursuing an undergraduate degree in Classics and Political Science. During the summer of 2023, she participated in the internship program at the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi. Her responsibilities included contributing to the population of the PROVENANCE ARCHIVIO BONCOMPAGNI LUDOVISI ONLINE (PABLO) database and concurrently conducting research on correspondence between the French Court and the Boncompagni Ludovisi family. Vinya expresses gratitude to Dr. T. Corey Brennan and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for granting her the opportunity to collaborate on researching unexplored artifacts in the Boncompagni Ludovisi database. She feels deeply honored to have played a role in this noteworthy project.

Portrait by unknown artist of Ippolita Ludovisi (1664-1733), Princess of Piombino from 1700 and sovereign of Piombino from 1707, in Casino dell’Aurora, Rome. Collection HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi

Wonderful recounting of the life of Ippolita Ludovisi.

Thank you for bringing her to life!