By Hatice Köroglu Çam (Temple University)

Francesco Vanni (1563-1610), Sora and the Ducal Palace in 1604. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Easily overlooked in the archive of the Boncompagni Ludovisi family at the Casino dell’Aurora in Rome is a brief but notable letter of Monday 31 March 1681, that traveled a mere seven kilometers from Sora to Isola del Liri in southern Lazio, in the territory of Frosinone. Here Luigi Bizzarri (1629-1698), the head of Sora’s Jesuit College, wrote in a highly protective manner to Princess Maria Ruffo di Bagnara (1620-1705), the mother of Prince Antonio I Boncompagni (1658-1731), providing an update on her son’s well-being at the school.

Young Antonio was not an ordinary student at this Jesuit college. The head of the Boncompagni family and his wife held the hereditary title of Duke and Duchess of Sora. Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni (1502-1572-1585) had purchased the fiefdom in 1579 from the Della Rovere family, and given it to his son Giacomo Boncompagni (1548-1612), who in turn established himself in a spectacular palace above a waterfall near Sora in Isola del Liri.

Johann Woelfle, Der Fall des Liris bei Isola di Sora (1837-1842). Credit: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Art & Architecture Collection, The New York Public Library

The contents and tone of the letter suggest that Antonio’s mother Maria Ruffo, the Duchess of Sora, likely wrote to the head of the Jesuit college first and Bizzarri is responding with this letter to reassure her and give her peace of mind. The document provides a highly personal glimpse of the nature of Antonio’s education under the Jesuits, specifically the central position of religious observance and spiritual preparation. Bizzarri explains that any delay in Antonio’s return to the family castle of Isola del Lira is due to religious activities at the College, especially those connected with Easter Sunday, which in that year would fall on 6 April. Bizzarri reassures Prince Antonio’s mother that her son is doing well and advises her not to worry, twice emphasizing both that the College serves as a home for its students, and that Antonio is under the protection of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The nurturing tone of this short letter is striking. But it also offers a window into Antonio’s educational path and highlights the significant role mothers played in overseeing their children’s schooling during the 17th century. The document also sheds new light on the formal relationship of Maria Ruffo to the Jesuit college. Here is the text and a translation:

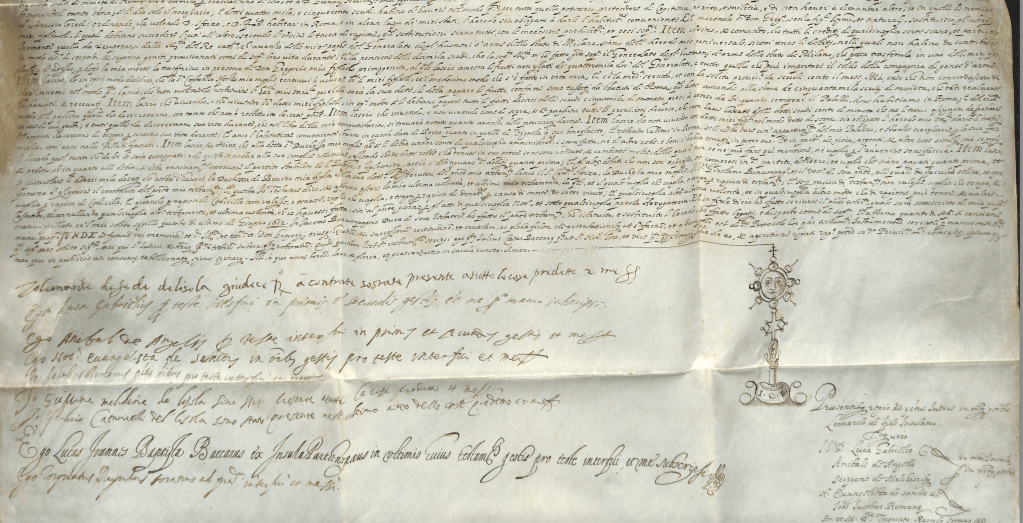

Letter (31 March 1681) from the Jesuit father Luigi Bizzarri to Maria Ruffo, Duchess of Sora. Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi, Casino dell’Aurora, Rome, from the collection “Letters from Sovereigns” (no archival number). Collection HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi.

Illustrissima et eccellentissima signora, e Padrona collendissima, Vostra Eccellenza stia pure allegramente perché l’Illustrissimo Signore Don Antonio suo figlio sta bene con me qui in Collegio domesticamente, e la Santissima Vergine lo farà ritornare contento. Ella non ha occasione d’affliggersi perché l’assicuro, che la dimora in questo Collegio (che pur si puol dire casa loro) che si degna di fare il buon giovane, non è per mutatione alcuna; ma solamente per fare una buona confessione, e celebrare bene la santa Pasqua, quale prevengo a pregarla a Vostra Eccellenza, per augurarglila di presenza, piacendo alla Santissima Vergine, che li conceda ogni vero bene. Sora 31 Marzo 1681, Di Vostra Eccellenza Humilissimo et Obligatissimo servitore, Luigi Bizzarri da Compagnia di Gesù

“Most illustrious and most excellent Lady, and most cultivable Patron, may your Excellency be cheerful because the illustrious Lord Don Antonio, your son, is domestically comfortable with me here in the College, and the Most Holy Virgin will make him return content. You have no reason to grieve because I assure you that the delay in this College (which can also be called their home) that the good young man sees fit to make is not due to any change; but only to make a good confession, and to celebrate properly Holy Easter, which I beg to ask of your Excellency, to wish him it presently, pleasing the Most Holy Virgin, who grants them every true good.” [signed] Sora, 31 March 1681, Your Excellency’s Most Humble and Most Obligated Servant, Luigi Bizzarri of the Society of Jesus

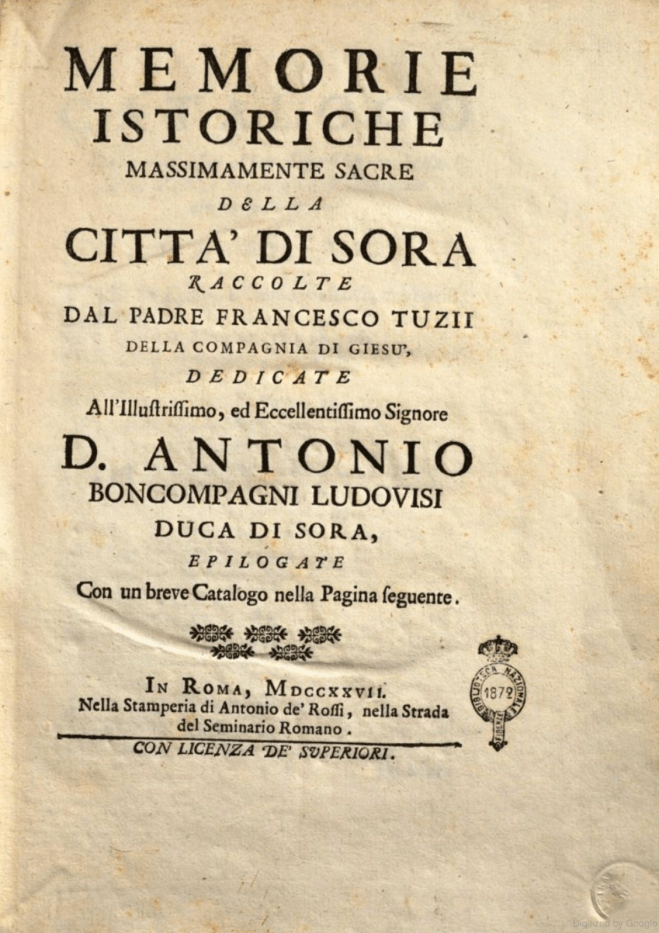

Luigi Bizzarri was clearly a charismatic figure in Jesuit education. We have a revealing near-contemporary sketch of his life, thanks to the Jesuit historian Francesco Tuzi, in his 1727 Memorie istoriche massimamente sacre della città di Sora, which he dedicated to our Antonio Boncompagni. Tuzi relates that Bizzarri, a native of Monte Santo in Italy’s Marche region, was educated at the premier Jesuit school, the Collegio Romano, whose great patron had been Gregory XIII Boncompagni. By this time missionaries from the Society of Jesus—founded in 1540 by S Ignatius of Loyola—had spread well across the globe and established numerous colleges where the study of the arts, sciences and theology flourished. Bizzarri himself first took up posts at Jesuit colleges in Florence and Sezze (southwest Lazio). In early November 1675, he was appointed as the rector of the Jesuit College of Sora, which had been shuttered for some years. “For the first decade, he managed it with only one [Jesuit] brother”, says Tuzi. “And in the following years, he had a few teachers but no others.” There Bizzarri remained in charge for two decades. He died in Sora three years after what seems to have been forced retirement, on 31 December 1698.

Tuzi in his biographical notice of Luigi Bizzarri offers many items of direct relevance to this letter. He describes how Bizzarri energetically combined “spontaneous” teaching with spiritual work, at the school and in the general territory of Sora. He reports that Bizzarri affected the guise of a beggar and “always mortified himself daily with disciplines, hair shirts, and iron chains”, until the Jesuits eventually made him stop. “In his old age, suffering great harm from sitting still in the confessional” due to sciatica, “he would remain immobile for five continuous hours.” He also convinced many of the people of Sora that his intercession is what protected them from droughts or floods. Tuzi also says that Bizzarri “regularly assisted the Noble Duchess”, i.e., Maria Ruffo Boncompagni, “always responding to any call to the Ducal Palace of the Isola [del Liri].”

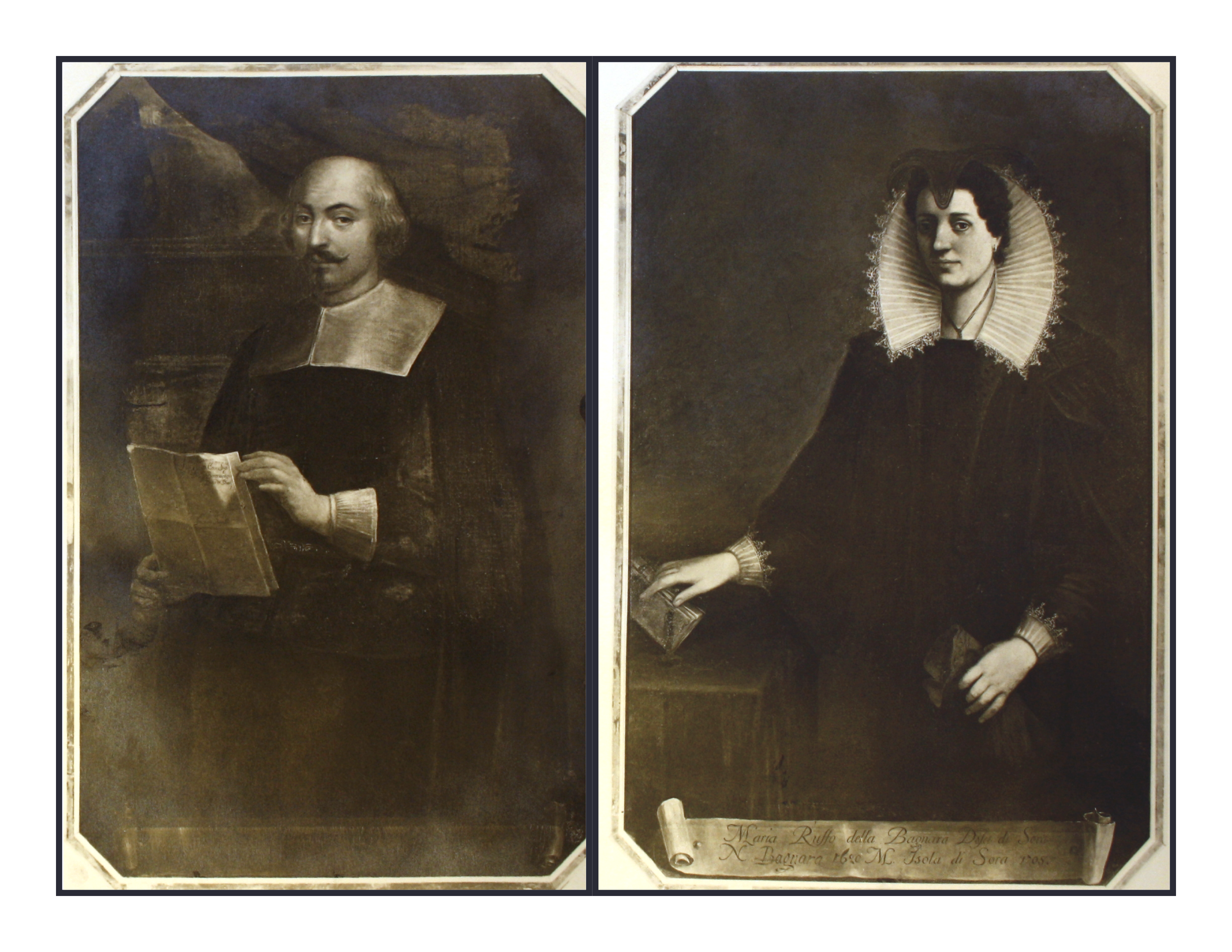

Ugo Boncompagni (1614-1676) and his wife Maria Ruffo di Bagnara (1620-1705). Collection HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

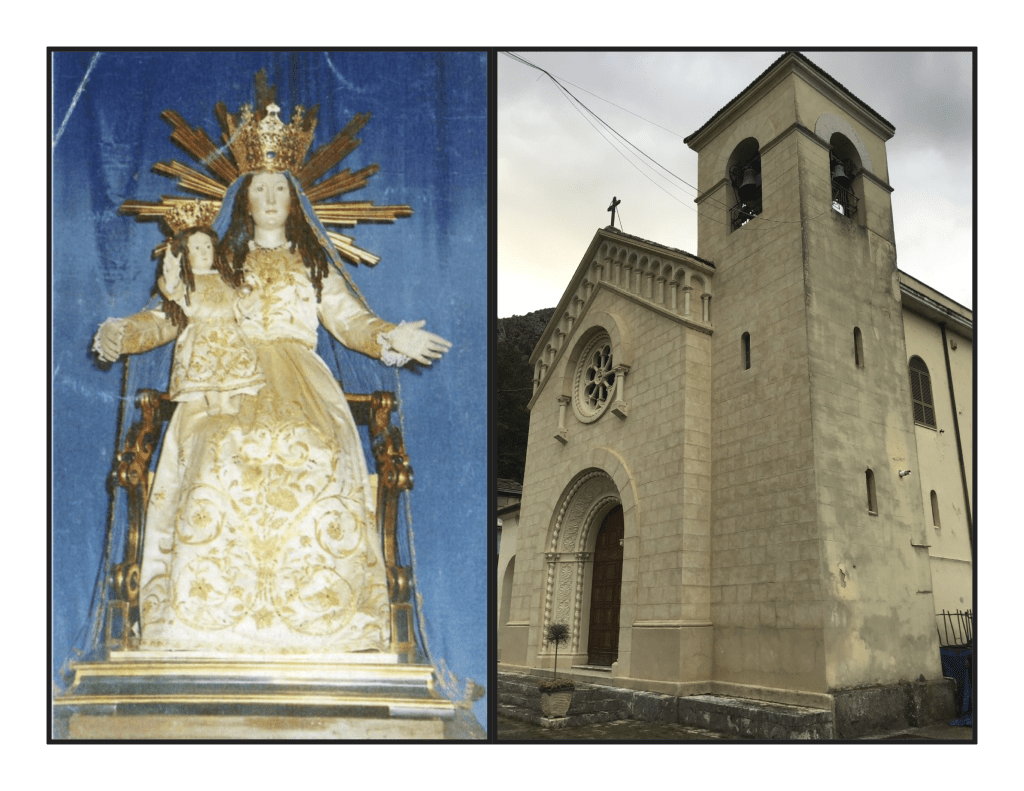

Most strikingly, Tuzi narrates how Bizzarri (it seems in 1679) found a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary in a rural shrine at Valfrancesca, on the road along the Liri river just north of Sora. Bizzarri ascribed miraculous properties to this image, which attracted pilgrims from far and wide. “Many attest to finding him there for hours in prayer, immobile like a statue, with a face glowing as if on fire”, says Tuzi. Eventually Bizzarri raised 4000 scudi to build a new chapel to the Madonna of Valfrancesca, dedicated in 1683. “He began to go around the city [of Sora] every Saturday”, reports Tuzi, “with an image of the same Virgin around his neck, asking for alms for his new church.” Despite some evident discomfort on the part of his fellow Jesuits, “he never abandoned this practice for twenty years, regardless of rain or other impediments, carrying the Sacred Image with his hands raised high for at least three hours.” It seems certain that when Bizzarri in his letter to Maria Ruffo invokes the protective powers of the Blessed Virgin Mary, he is thinking specifically of the Madonna of Valfrancesco. The statue is still used at Sora to pray against droughts or floods.

The Madonna of Valfrancesco (from vintage postcard) and her church, dedicated 1683 (Wikimedia Commons).

Prior to the discovery of this letter, no details were known about the educational journey of Antonio I Boncompagni at the Jesuit College in Sora. Notably, Giuseppe Felici, the family’s last archivist, wrote a biography (unpublished) of Antonio I, but he did not mention his education. This short letter must have escaped his notice.

The most surprising thing about this letter is Antonio’s age at the time it was sent. Antonio I and his twin brother Filippo were born at Isola di Sora on 10 April 1658, the tenth and eleventh of thirteen children of Maria Ruffo di Bagnara (1620-1705) and Ugo Boncompagni (1614-1676), the great-grandson of Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni. So Antonio was just a week and a half from his 23rd birthday, and still a student at the College.

The brothers Gregorio (1642-1707) and Antonio (1658-1731) Boncompagni, sons of Ugo Boncompagni and Maria Ruffo. Collection HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

At this point in 1681, all of Antonio’s siblings were alive except for two: a sister Agnese, born in 1646 who died at two and a half years, and his twin brother Filippo, who had died of smallpox at Genova in December 1679. This recent death may explain in part why Maria Ruffo, who had lost her own husband in 1676, was so concerned for the well-being of the surviving twin. Antonio was now the third-eldest male Boncompagni, behind brothers Gregorio (born 1642) and Francesco (born 1643, who would die in 1690).

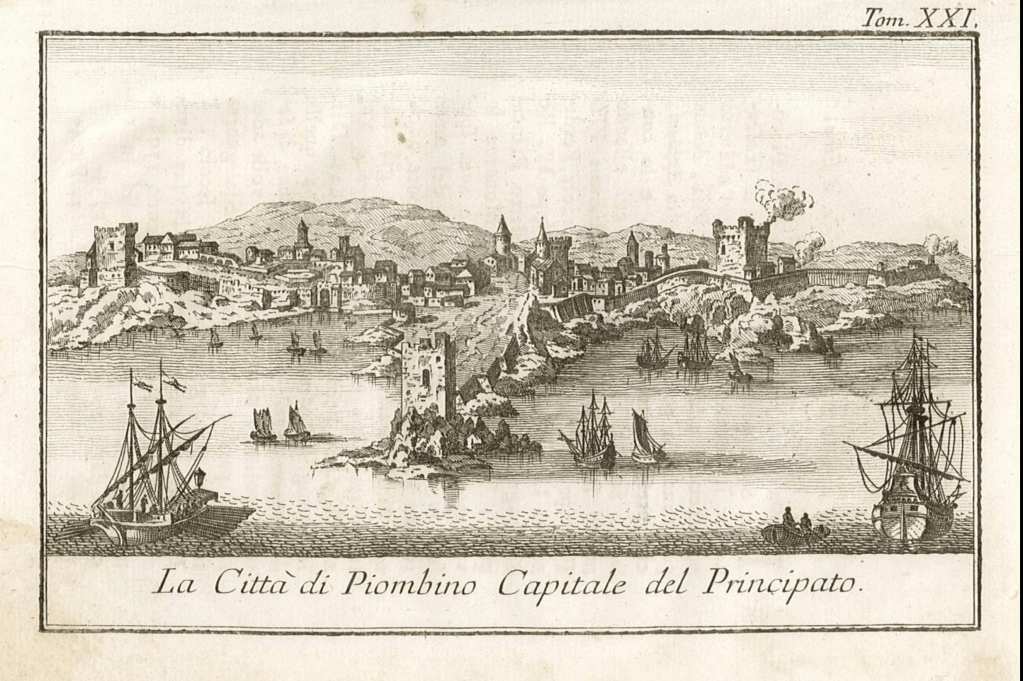

The year 1681 proved to be a crucial one for Boncompagni fortunes. On 16 October 1681, Antonio’s eldest brother Gregorio married Ippolita Ludovisi (1663-1733), grand-niece of Pope Gregory XV Ludovisi (1556-1621-1623), who had inherited from her father Niccolò Ludovisi (1613-1664) the principality of Piombino with part of the island of Elba. This union saw an actual merger of the two families, which in turn elevated the Boncompagni lineage to the rank of Princes of Piombino.

Thomas Salmon (1679-1767), view of Piombino (ca. 1740-1756). Credit: Wikimedia Commons

However, the marriage faced complications. Ippolita’s succession rights had long been contested by her elder sister, Olimpia Ludovisi (1656-1700), then a nun at S Francesca Romana a Tor de’Specchi. Olimpia obtained a favorable judgment from the Neapolitan Grand Court of the Vicaria against Ippolita’s claim to succession, which considered the principality of Piombino a fief not of Spain but of the Kingdom of Naples. Nevertheless, Olimpia’s death in 1700 cleared the path for Ippolita’s succession. On 27 February 1701, the new king of Spain, the seventeen year old Philip V (reigned 1700-1746), himself confirmed Ippolita as the legitimate heir to the principality.

Portrait of Ippolita Ludovisi (1663-1773) at Casino dell’Aurora. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Gregorio and Ippolita were to have seven children in all, a son and six daughters in the years 1684 through 1697. However the first-born, Ugo, died at the age of two in 1686, creating an issue with the line of succession for the Boncompagni family. In her 2015 work Accounting for Affection: Mothering and Politics in Early Modern Rome, Caroline Castiglione discusses Gregorio’s approach to resolving the heir problem: “Gregorio…eventually came to see the impossibility of producing a male heir. He had, in his youth, at least once sought an extramarital solution to this problem, but this too had yielded a daughter.”

As a result, on 29 March 1702, with papal dispensation, at the age of forty-four, Antonio married his niece, Maria Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi (1686-1745)—the sixteen-year-old daughter of his eldest brother. It was a radical solution to keeping the family’s main line alive. The couple had five children, among whom three were sons: Maria Olimpia (1703-1705), Niccolò (1704-1709), Francesca Cecilia (1705-1775), Gaetano (1706-1777), and Pier (Pietro) Gregorio (1709-1747). It was the fourth-born, Gaetano, who in the end became the family’s heir.

Antonio Boncompagni evidently attached particular significance to his prolonged education at the Jesuit College. That emerges from a reading of Paolo Emilio Bellisario’s comprehensive 2009 work, Il Borgo Ritrovato: S. Spirito e il Collegio Gesuitico Di Sora. There Bellisario provides extensive historical and chronological insights into the presence of the Jesuits at Sora, as well as the history of the church S Spirito (originally a medieval foundation) within their college complex, and the contributions of Antonio I and his wife Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi to it all.

Contemporary view of the ex-Jesuit College at Sora complex, with church of S Spirito at right. Credit: Google Streetview

In short, Bellisario explains that the Jesuits established their presence in Sora near today’s Piazza Ortara initially by using existing medieval houses that belonged to the Archispedale of Santo Spirito in Sassia in Rome. This marked the start of their efforts to establish a Jesuit college in the area. They also acquired the small medieval church of S Spirito, which did not meet their requirements.

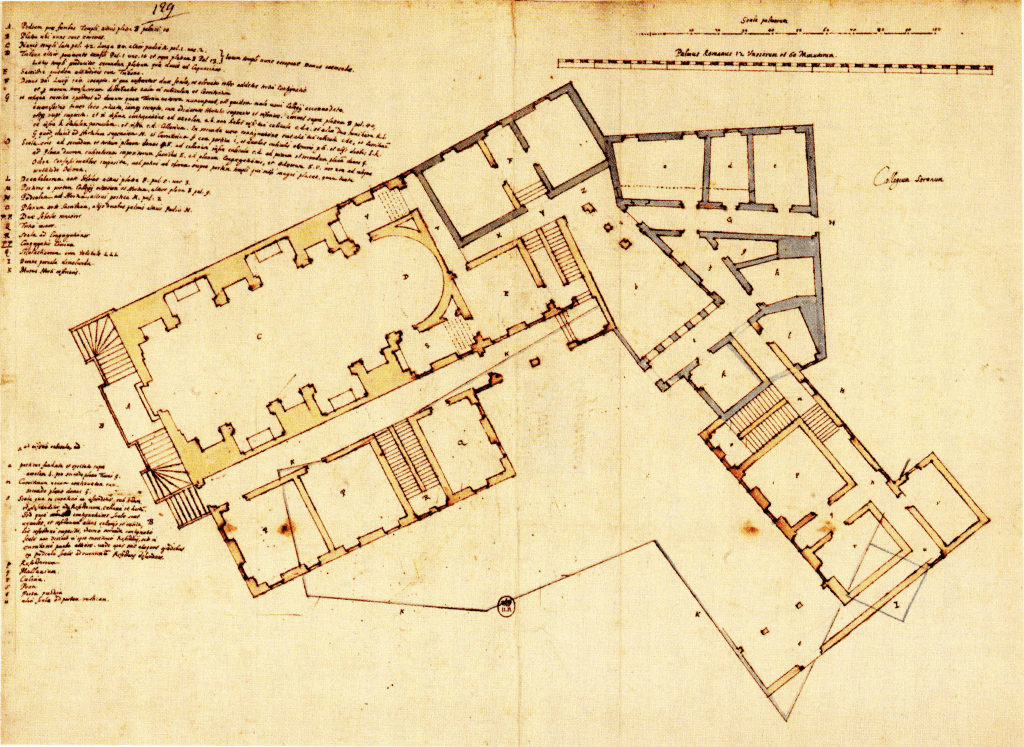

Original first project for the Jesuit College at Sora from 1611. Credit: Paolo Emilio Bellisario, Il Borgo Ritrovato: S. Spirito e il Collegio Gesuitico Di Sora (2009)

Bellisario provides the approved first plan of the Jesuit College at Sora, dating back to 1611—still during the lifetime of the papal son Giacomo Boncompagni. The college only later expanded to incorporate the surrounding areas, which were once home to gardens belonging to neighboring religious communities. In its developed form, the Jesuit College consisted of a palazzo housing both educational facilities and the residence of the Jesuit Fathers, accompanied by the adjacent church of S Spirito.

Significantly, Bellisario underscores the immense impact on the College of Costanza Sforza (1560-1617), who in 1576 married Giacomo Boncompagni and shortly afterward became Duchess of Sora. The couple had fourteen children, with their son, Gregorio I Boncompagni (1590-1628), becoming the second Duke of Sora.

Detail of will of papal son Giacomo Boncompagni (1548-1612), from the Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi in Casino dell’Aurora. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Now it happens that Giacomo’s will, dated 1612, discovered in 2010 by HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi in the family archive at Casino dell’Aurora, allocated 300 ducats annually for the construction of a college. Bellisario mentions that upon Giacomo Boncompagni’s death on 26 August 1612, Costanza Sforza, prompted by Bishop Girolamo Giovannelli, dedicated that sum for the permanent construction of a new building in Sora to be used as a College of the Society of Jesus. Furthermore, Sforza, with the approval of Pope Paul V Borghese, acquired all the medieval real estate assets owned by the Archispedale of Santo Spirito in Sassia within the town.

Lavinia Fontana, portrait of Costanza Sforza (1550-1617), Duchess of Sora (1550-1617), 1594. Credit: Wikimedia Commons. For the story of the rediscovery of this portrait in Sweden and its sale in 2016, see here.

Bellisario emphasizes the challenges involved in the development of the Jesuit College, which turned out to be a complex and long-evolving project. In 1613, the Jesuits formally took control of the properties that were intended to be used for the College. Yet the building of the College took place over a massively extended period, from 1614 to 1727, with many delays and changes in the plans and designs after the formal breaking of ground on 26 July 1615 and an inaugural mass in the old medieval church on 1 January 1621.

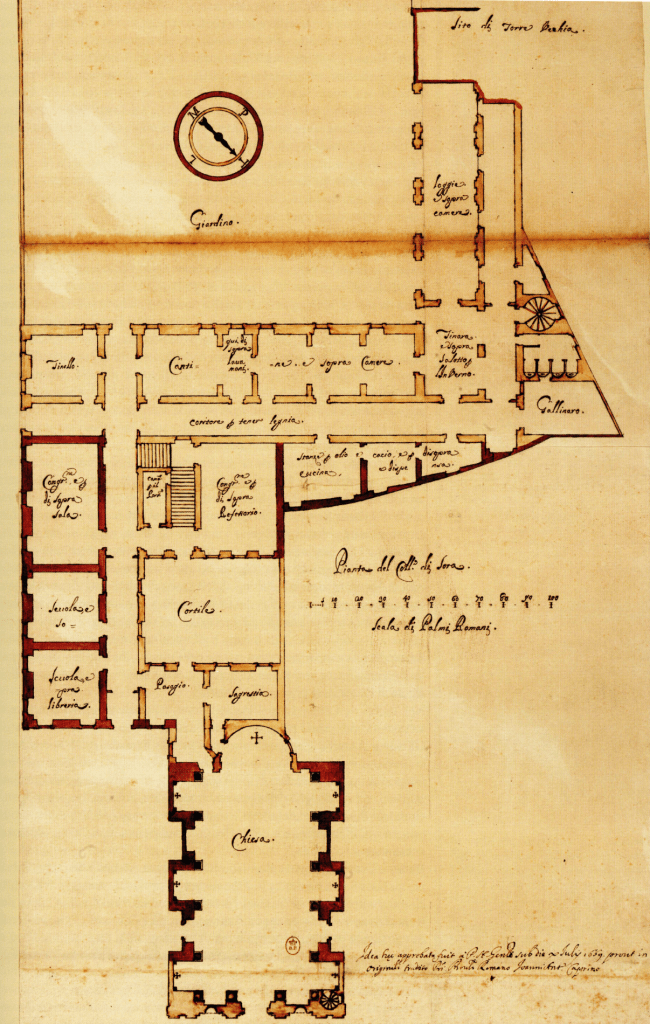

For example, as Bellisario notes, in early February of 1621, the College’s Rector received a proposal for a revised approach to housing arrangements, indicating that structural development was still undergoing modifications and adjustments. On 28 February 1621, Bishop Giovannelli took the decisive step of deconsecrating the medieval S Spirito church; the new Boncompagni-built church that would replace it was consecrated only in 1727. Other challenges included a dispute with the Franciscans, which necessitated a radical revision in 1633. Despite setbacks, progress continued, with a thorough revision of the project approved on 10 July 1669.

Approved variant of the first project for the Jesuit College at Sora, dated 10 July 1669 (Bibliothèque Nationale de France). Credit: Paolo Emilio Bellisario, Il Borgo Ritrovato: S. Spirito e il Collegio Gesuitico Di Sora (2009)

Yet by November 1675 the College had been inactive for several years, and it was Luigi Bizzarri who was given the responsibility of re-establishing and improving it. Bellisario in his work provides much of value on Bizzarri’s efforts to revive and maintain the College of Sora through key appointments, with close examination of documents that illustrate the College’s condition and staffing during the relevant period. He notes that Bizzarri was appointed to the College of Sora specifically “in order to restore it in revenues and improve it in construction”. Bellisario also points up a detail quite relevant to our 1681 letter: that Bizzarri stayed in the Boncompagni ducal palace at Isola del Liri as well as in the Sora College, which certainly shows the close connection between this Jesuit, the family, and the school.

Contemporary view of Isoa del Liri, with ex-Boncompagni palace at upper left, now known as Castle Boncompagni Viscogliosi [Wikimedia Commons]

After Bizzarri’s death in 1698, Anton Giorgio Giannelli succeeded him and served in this role until 1 January 1712. Bellisario includes a document which provides insight into the state of the college at that time, recording a visit by Monsignor Matteo Gagliani in 1706. During Gagliani’s visit, the college was staffed by four Jesuit Fathers and two laypeople, indicating the small number of personnel involved in its operation.

This brings us back to the 1702 marriage of Antonio I Boncompagni to his niece Maria Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi. Bellisario emphasizes that the pair made substantial donations that were crucial for the completion of the Jesuit College. Thanks to their financial support, the entire college complex at long last was completed in 1723, following the revised plan of 1669. The construction incorporated Roman-era materials from the so-called Temple of Serapis, which allegedly had collapsed in the year 161 in association with the martyrdom of S Julian of Sora.

Portrait of Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi (Sora 1686—Rome 1745), in the habit of a widow, following the death of her husband Antonio (I) Boncompagni (†1731) [collection HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome]; and her tomb monument in the church of S Maria del Popolo [Wikimedia Commons]

Throughout its long and complex history, the Jesuit College in Sora reflected the evolving architectural and social landscape of the region and the enduring legacy of Jesuit education and patronage. What finally became of the complex? In the second half of the 1900s, the College—with the exception of the church of S Spirito—was converted into Sora’s town hall, showing its continued significance and adaptation to the needs of the community.

So this short letter written by Luigi Bizzarri to Maria Ruffo, dated 31 March 1681, offers unexpected insight into the educational journey of Antonio I Boncompagni at the Jesuit College in Sora. While primarily aimed at reassuring a concerned mother about her son’s well-being, the letter highlights the importance of maternal involvement in education and the privileged status of the Boncompagni family in the Sora institution. Indeed Bizzarri specifically identifies the recently widowed Maria Ruffo as the school’s patron, continuing a role first held by Costanza Sforza, the daughter-in-law of Gregory XIII Boncompagni.

Although the document raises questions about Antonio I Boncompagni’s academic progress—again, he was almost 23 years old at the time—it does underscore the nurturing role of the Jesuit educator Bizzarri. Indeed, his correspondence enhances our understanding both of the family’s educational choices and the institutional approach to familial relationships within the Jesuit educational framework. It also corroborates Paolo Emilio Bellisario’s work on Sora, where he highlights the substantial contributions made to the Jesuit College and the new church of S Spirito by its first patron, the Boncompagni princess Constanza Sforza, and later Antonio I Boncompagni and his wife Maria Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi.

Hatice Köroglu Çam (she/her) is currently pursuing her PhD in Italian Renaissance art at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art and Architecture. She graduated with honors, achieving summa cum laude, from Rutgers University in 2022 with a B.A. in Art History. During the spring and summer of 2022, Hatice completed an internship at the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi project. Over the past two years, Hatice has delved deeply into her research on a 16th-century statue of Pan located in the gardens of the Casino dell’Aurora in Rome. She writes, “I extend my deepest gratitude to Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi and Professor T. Corey Brennan for graciously granting access to this invaluable archival document. Additionally, I am sincerely thankful to Dr Paolo Emilio Bellisario for his generous contribution to this research. His efforts, including sending a physical copy of his book Il Borgo Ritrovato: S. Spirito e il Collegio Gesuitico Di Sora (2009) from Italy to the USA and providing information via email, have been immensely appreciated.”

The ex-Jesuit College at Sora, now the Palazzo Comunale (vintage postcard).

Leave a comment