‘La Sala di Papa Boncompagni’ in Rome’s Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi per le Arti decorative. The preparatory sketch discussed in this article can be seen on the rear right-hand wall. Credit: Allegra Brennan

By ADBL Editor Corey Brennan with Allegra Brennan (SUNY FIT ’28)

Talk about hiding in plain sight. In Rome’s stunning Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi, in ‘La Sala di Papa Boncompagni’ (= Gregory XIII, 1502-1572-1585), amidst all the major pieces it’s easy to miss a small oil on canvas with tiny figures, mounted on a side wall. An antique chair is placed in such a way that close examination of the painting is difficult. However it’s clear that only three quarters of the composition is captured in its gilded frame.

The explanatory card for the painting (46.5cm x 37cm, with frame) seems an afterthought, resting on a nearby fireplace mantel behind a pair of miniature horses in bronze. The label explains that it is a bozzetto, or preparatory sketch, by the Roman artist Pietro Gagliardi (1809-1890) for an “Allegory of Time”, executed between 1855-1858. It further specifies that the work was meant for the decoration of the new (i.e., mid-nineteenth century) wing of Rome’s Casino dell’Aurora of the Boncompagni Ludovisi, picturing episodes from the life of Gregory XIII Boncompagni. And that the Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi acquired this piece in 2017. The museum’s catalogue adds that it was purchased from a private collection in Bologna.

Pietro Gagliardi’s study for an “Allegory of Time” (1855-1858) in Rome’s Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi. Photo: Allegra Brennan

Though the left quarter of the sketch is wholly missing, it’s obvious from the general arrangement of the composition that this is a design for a ceiling. At what should be the center is a striking image of a winged Father Time flying left and looking right, against a bright blue sky with white clouds. He holds a scythe with his right arm and raises aloft an hourglass with his left—standard attributes of this personification since the Renaissance. Three winged putti join Time in flight, holding up elements of his long, unfurling banner that features (unfortunately illegible) lettering.

Detail of Father Time in Pietro Gagliardi’s study for an “Allegory of Time” in Rome’s Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi. Photo: Allegra Brennan

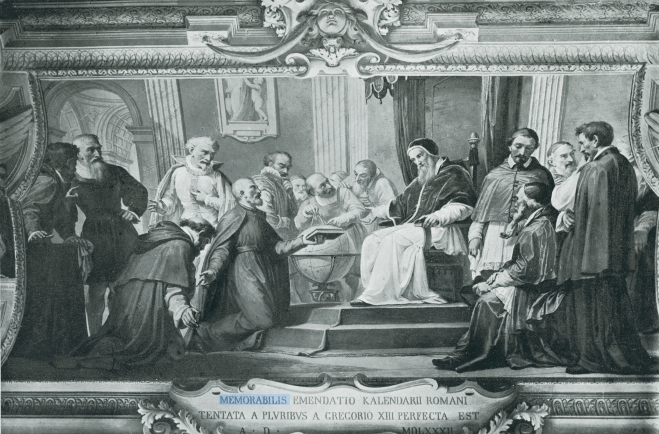

Below and above the “Father Time” centerpiece are depictions of two well-known episodes from the life of Gregory XIII: his reform of the calendar (1582) and his reception of the Tenshō Japanese embassy, the first to Europe (1585). Personifications of Fame (here, a seated female figure with wings blowing a trumpet) flank each of the two historical scenes.

Details of Gregory XIII’s calendar reform of 1582 (above) and his reception of the Japanese Tenshō Embassy of 1585 (below) in Pietro Gagliardi’s study for an “Allegory of Time” in Rome’s Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi. Photo: Allegra Brennan

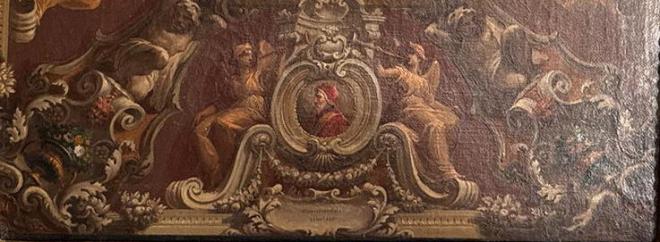

The right hand portion of the sketch shows a portrait of Pope Gregory XIIII in profile, wearing camauro and mozzetta, within an ornate painted frame. Personifications of Fame are seated at either side of the Pope, while two Atlantes occupy the right hand corners of the painting.

Detail of portrait of Gregory XIII Boncompagni flanked by personifications of Fame and Atlantes in Pietro Gagliardi’s study for an “Allegory of Time” in Rome’s Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi. Photo: Allegra Brennan

It is to the immense credit of Allegra Brennan (SUNY Fashion Institute of Technology ’28, currently studying at American University in Rome) to have spotted Pietro Gagliardi’s bozzetto in the Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi and associated it immediately with his mural work on the piano nobile of the Casino dell’Aurora. There in the years 1855-1858, in a new wing of the Casino to the southeast, Gagliardi painted in fresco a ceiling and four upper walls of a sala, covering well over 60 square meters. (The dimensions of the room, originally a grand space for dining, are 9.28m x 5.90m, with a height of 5.73m.)

Guercino’s Fama (1621) in Rome’s Casino dell’Aurora, with frame by Agostino Tassi. Credit: Laboratorio Diagnostico per i Beni Culturali – UniBo / Storia dell’Arte 157 (2022)

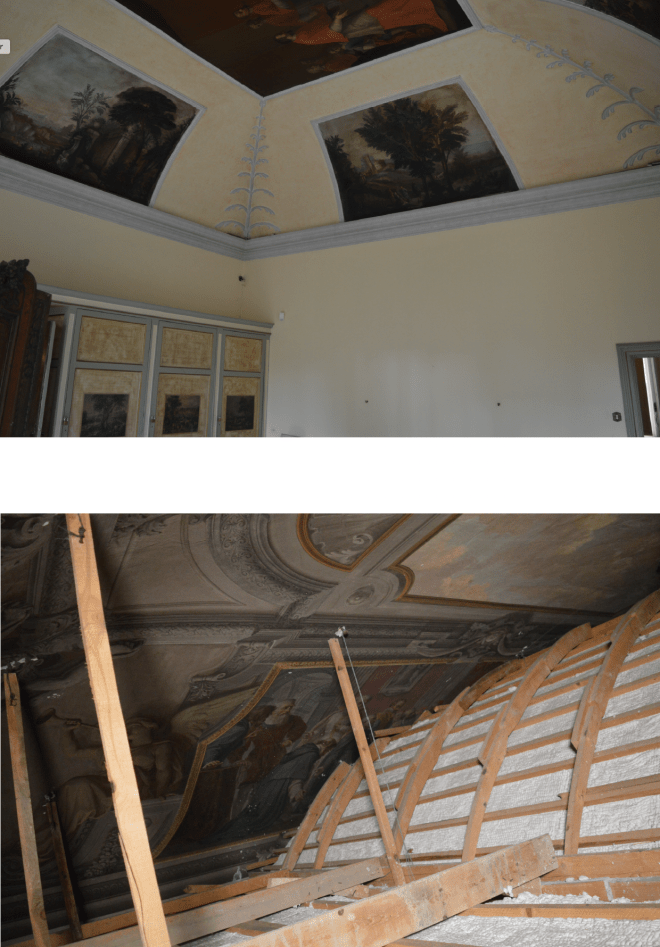

Originally, one entered this dining space primarily by passing through the large central sala that boasted Guercino‘s renowned ceiling painting of Fame (1621), and then, after traversing two smaller rooms, through a door situated at a point that corresponds to the lower right-hand portion of our bozzetto. Today Gagliardi’s massive work is no longer visible, since in the mid-20th century the sala was split into three rooms, each with a false ceiling that hides the 19th century fresco cycle.

Portion of the Sala da pranzo in the mid-19th century southeastern wing of the piano nobile of Rome’s Casino dell’Aurora, with views of the mid-20th century vault from below (top image) and within (bottom image). Credit: TC Brennan

The story of the discovery of Gagliardi’s painting (a joint enterprise of Corey Brennan with ADBL board member Anthony Majanlahti and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi) unfolded on this blog for four years, starting in 2013. It was only in 2016, thanks at first to an endoscope inserted through a light fixture, that a portion of Gagliardi’s masterpiece—about a third of the whole—came into view. By chance it included the section missing from the bozzetto in the Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi.

Image from Deseret Evening News (Salt Lake City UT), 27 February 1904, showing left hand portion of the Gagliardi sala as one enters. The art on the lower portion of the walls was installed for an exhibition of the American Academy in Rome, which for twelve of its earliest years (1895-1906) rented the Casino dell’Aurora from the Boncompagni Ludovisi.

As it happens, there exists in the Museo di Roma—Palazzo Braschi a separate bozzetto by Gagliardi of a section of the ceiling, showing only the Japanese embassy of 1585. There is also other evidence for the now-hidden work. I found in the Boncompagni Ludovisi family archive at Casino dell’Aurora two excellent photographs from 1904, reproducing in detail the Gregorian Calendar and Japanese embassy scenes. Furthermore, also (quite coincidentally) from 1904, I found printed in several US newspapers an image of a portion of Gagliardi’s room, from a time when the young American Academy in Rome was renting the Casino.

Unpublished photograph (1904) of the Gregorian Calendar scene in Pietro Gagliardi’s fresco cycle for the piano nobile of the Casino dell’Aurora. Credit: Collection HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Here is the fullest written description of the frescoes, from Gaetano Moroni, Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica da S. Pietro sino ai nostri giorni [vol. 99 (1860) p. 240 s.v. Villa], giving most of the key data:

“”Now the small palace of Aurora, thanks to a new addition to the building designed and directed by the cavaliere Nicola Carnevali, a skilled Roman architect, has become a handsome palace. And there, among so many beautiful rooms, one is covered by a beautifully shaped vault in whose compartments, adorned with stuccoes representing various kinds of arabesques by the skilled artist Antonio Urtis, two fresco paintings by the knight Pietro Gagliardi, an esteemed Roman painter, are offered for admiration. They depict: one, the Reception in Rome by Gregory XIII Boncompagno of the Japanese ambassadors; the other, the Correction of the Calendar made by that great Pope. Moreover, the aforementioned painter portrayed Gregory XIII and Cardinal Ludovisi. All works were commissioned by don Antonio [III] Boncompagno Ludovisi, Prince of Piombino.”

Detail of the Japanese Embassy scene in Pietro Gagliardi’s fresco cycle for the piano nobile of the Casino dell’Aurora. Credit: Nicholas Brennan

Oddly enough, the most comprehensive and authoritative work that treats the Casino dell’Aurora, Boncompagni Ludovisi family archivist Giuseppe Felici’s Villa Ludovisi in Roma (1952), makes no mention of Gagliardi and this important sala. (He also omits Caravaggio‘s “Jupiter, Neptune, Pluto” on the same floor.)

From the 2019 MUDEC Milan exhibition “Quando il Giappone scoprì l’Italia”. At its center: black and white photograph (1904, Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi) of Pietro Gagliardi’s fresco for the Casino dell’Aurora (1855-58) depicting the 1585 Japanese embassy to the West, inset with the painter’s bozzetto for the same (Museo di Roma).

However the “new” Gagliardi bozzetto spotted by Allegra Brennan (full disclosure: my daughter) is the first evidence that allows us to make sense of Gagliardi’s plans for the room as a whole. For instance, Moroni (cited above) mentions that the sala had complementary portraits featuring respectively Gregory XIII and Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi (1595-1621-1632). That of Cardinal Ludovisi is (with difficulty) accessible to camera, but the bozzetto offers us our first glimpse of the portrait of the Boncompagni pope. They are both medallion-style, and each positioned at the center of the short ends of this room.

Pietro Gagliardi’s medallion-style portrait of Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi (after that of Ottavio Leoni) in the sala da pranzo on the piano nobile of the Casino dell’Aurora. Credit: Nicholas Brennan

The depiction of Father Time flying with his three putti however is completely new and surprising. No description of the room ever mentions it. One supposes that the 1582 papal reform that instituted the Gregorian Calendar suggested the subject to Gagliardi. From our admittedly limited ability to view the original ceiling today, it does not seem to have been executed, at least in the dimensions that the bozzetto suggests. At any rate, none of the figures presently can be seen—only the blue sky and clouds.

Partial view of Pietro Gagliardi’s centerpiece for the sala da pranzo on the piano nobile of the Casino dell’Aurora. A mid-20th century vault blocks a view of the whole. Credit: Nicholas Brennan

On the other hand, the actual mural painting has at least one decorative element not found in the truncated bozzetto, namely a dragon without a tail, familiar from the Boncompagni family arms. One can be forgiven for forgetting that the Boncompagni and their pope Gregory XIII had nothing to do with the formation of the Casino dell’Aurora, merging with the Ludovisi only in 1681.

Pietro Gagliardi’s rendition of a Boncompagni dragon for the sala da pranzo on the piano nobile of the Casino dell’Aurora. Credit: Nicholas Brennan

There certainly is much to process here, and there will be even more in the event Pietro Gagliardi’s original sala is reconstituted with the removal of mid-20th century dividing walls and false ceilings. In Gagliardi’s original scheme as seen in the bozzetto, it appears the airborne Father Time at center served to connect the portrait of Gregory XIII Boncompagni (reigned 1572-1585) with that of the most prominent personality of the Casino dell’Aurora, Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi (1621-1632), as well as link two significant episodes from the Boncompagni papacy, one of which—the Japanese Embassy—fell shortly before the Pope’s death. As a hedge against the flight of Time is Fame, which Gagliardi represented in his composition eight times in all—in each case with a trumpet, as in the Guercino fresco on the same floor of the Casino dell’Aurora.

More significant details of Gagliardi’s masterwork will undoubtedly emerge, in the event that conservators manage to penetrate beyond the mid-20th century intrusions that today shield his mural art from view.

Pietro Gagliardi’s rendition of a Fame (one of eight) for the sala da pranzo on the piano nobile of the Casino dell’Aurora. Credit: Nicholas Brennan

Leave a comment