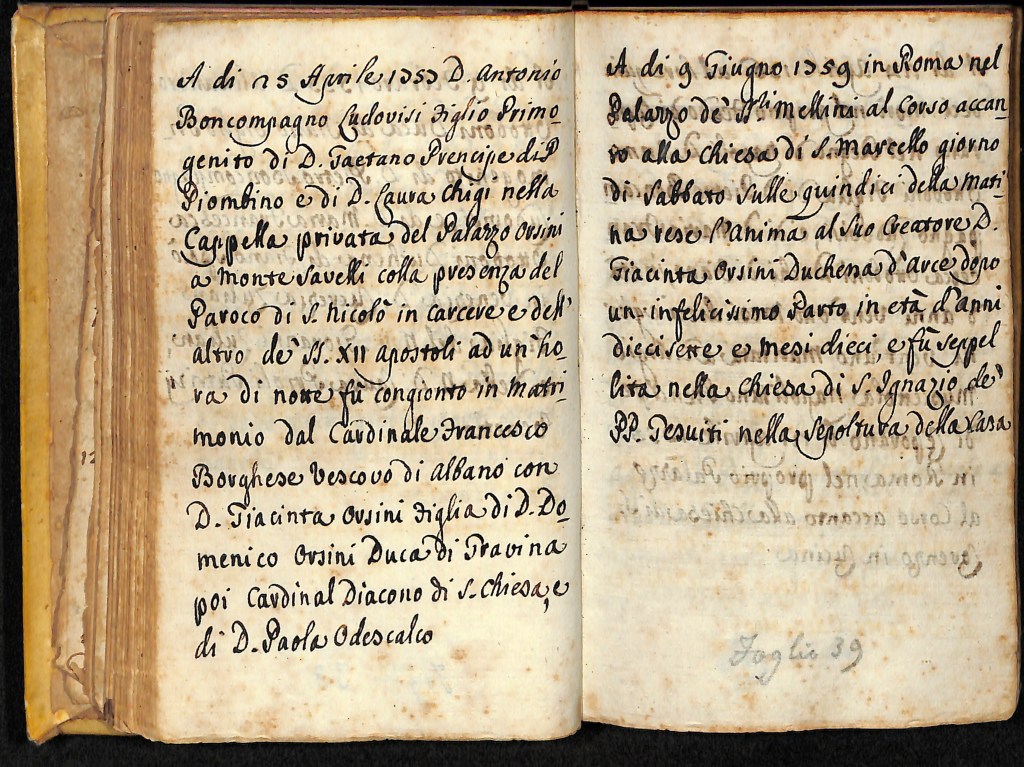

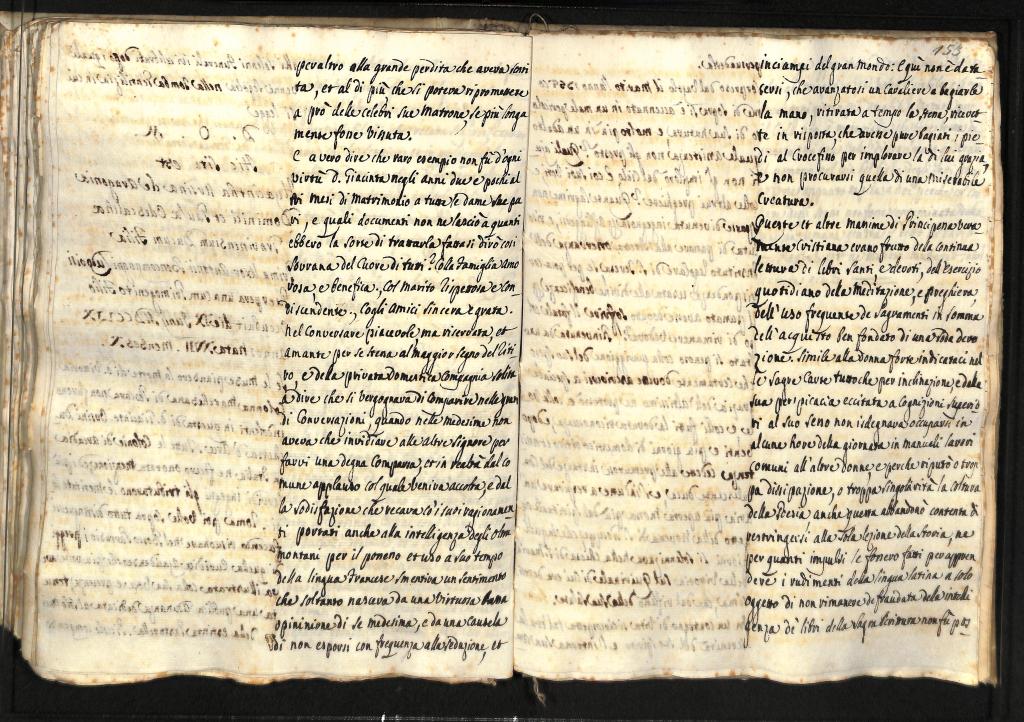

Pages from a formal diary maintained by the heads of Boncompagni and Boncompagni Ludovisi family—dating back in continuous succession to Giacomo Boncompagni (1548-1612), the son of Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

By Sarah Freeman (Morristown Beard School ’25)

For over 400 years, the heads of the Boncompagni and then Boncompagni Ludovisi have registered the most important milestones in their family history in a pocket sized book. One of the most poignant entries is found on the facing pages 38V-39R, detailing events just four years apart. The marriage of Giacina Orsini into the family and her death are noted in pages side by side:

April 25, 1755 “Don Antonio Boncompagno Ludovisi, firstborn son of Don Gaetano, Prince of Piombino, and Donna Laura Chigi, in the private chapel of Palazzo Orsini on Monte Savelli, in the presence of the parish priest of S Nicolò in Carcere and another from SS XII Apostoli, at one hour after sunset, was joined in marriage by Cardinal Francesco Borghese, Bishop of Albano, with Donna Giacinta Orsini, daughter of Don Domenico Orsini, Duke of Gravina, later Cardinal Deacon of the Holy Church, and Donna Paola Odescalco.”

June 9, 1759 “In Rome, in the Palazzo of the Mellini family on the Corso next to the Church of S Marcello, on Saturday around three in the afternoon, Giacinta Orsini, Duchess of Arce, after a very unfortunate childbirth at the age of seventeen years and ten months, passed away and was buried in the Church of S Ignazio of the Jesuit Fathers in the family tomb.”

Detail of portrait of Giacinta Orsini Boncompagni Ludovisi, Duchess of Arce, by Pompeo Batoni (1758). Private collection (auctioned 1997). Credit: https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-306136

Giacinta Orsini was born in Naples on 9 August 1741 to Don Domenico Orsini d’Aragona, the 15th Duke of Gravina, and his wife Princess Anna Paola Flaminia Odescalchi. Giacinta’s family on both sides was deeply rooted in Italy’s papal nobility: the Orsini gave the Church three popes, most recently Giacinta’s great-grand uncle Benedict XIII (1724-1730), and the Odescalchi boasted Innocent XI (1676-1689). Giacinta’s mother passed away giving birth to her brother, Filippo Bernualdo when she was just one years old, causing her father to become more connected to religion. Two years after her birth, in 1743, Giacinta’s father surprisingly was appointed a Cardinal. In this esteemed position, he was now eligible to be Pope, though we do not hear of him in competition for the position at the conclaves at which he participated.

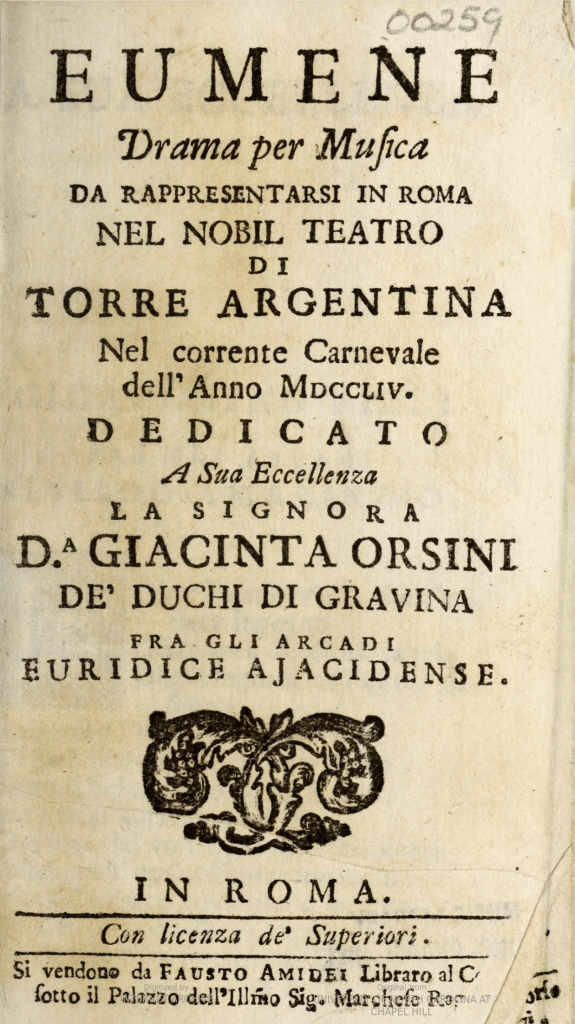

While there is little known about Giacinta’s early life, it is evident that by her earliest teens, she was writing Latin and Italian poetry, and other contemporary artists were also dedicating their works to her. After receiving a well-rounded education under the supervision of her father from a variety of tutors, at age 13 she became a member of the Academy of the Arcadians.

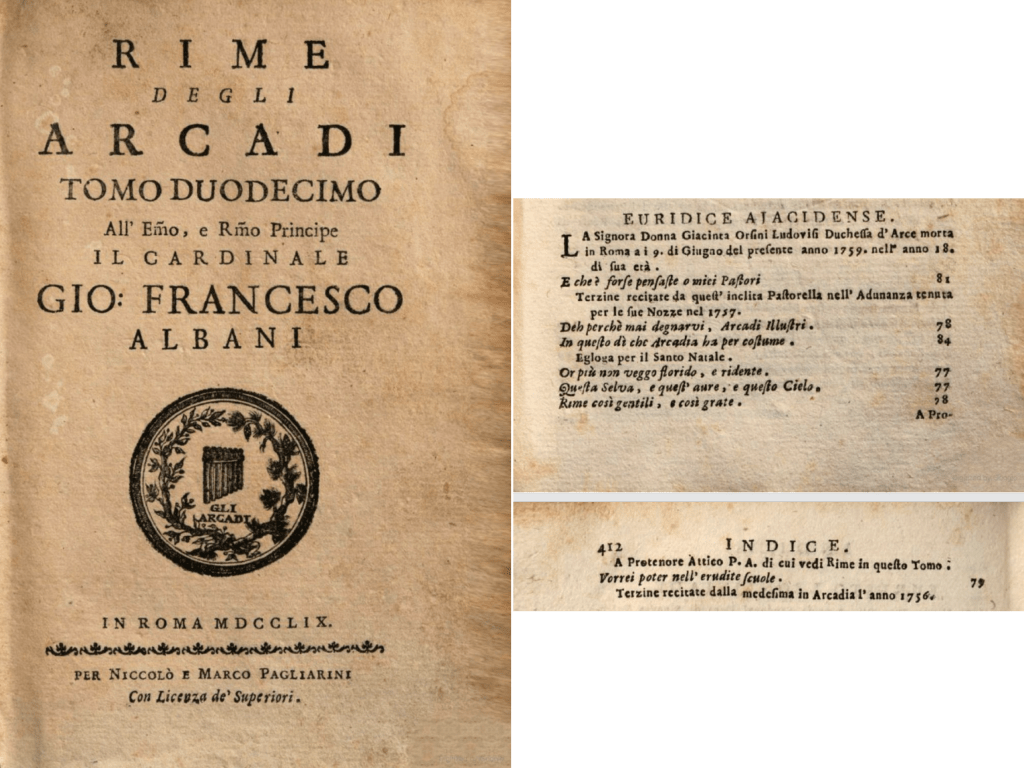

Seven poems in Italian of Giacinta Orsini were published posthumously in the 1759 edition of Rime degli Arcadi (volume 12 in the series). Credit: GoogleBooks

The Arcadians were a literary society of elite Roman men and women. Founded in 1690, members published under false names; however, their aliases were known to those in the group and freely disseminated elsewhere. The Arcadians boast influential alumni/ae, including Carlo d’Aquino, Carlo Alessandro Guidi, and Petronilla Paolini Massimi. This elite group lasted for centuries. Giacinta wrote under the pen name ‘Euridice Ajacidense’, producing a number of poems in Italian, especially sonnets.

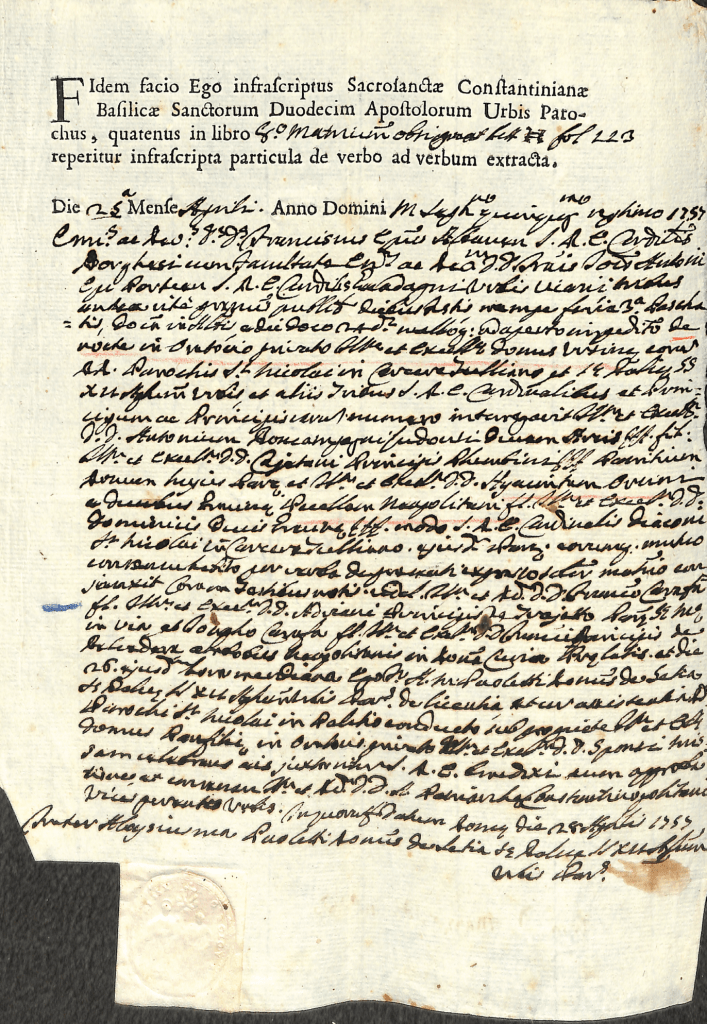

Marriage contract (drawn up 25 April 1757) of Antonio (II) Boncompagni Ludovisi and Giacinta Orsini. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

In July of 1757, Giacinta married Antonio (II) Boncompagni Ludovisi. The wedding was held in the private chapel of Palazzo Orsini on Monte Savelli in Rome, officiated by Cardinal Francesco Borghese. This wedding was a large event with a cantata and a banquet. Her marriage, which many viewed as a well-matched union, was celebrated by Arcadian poets.

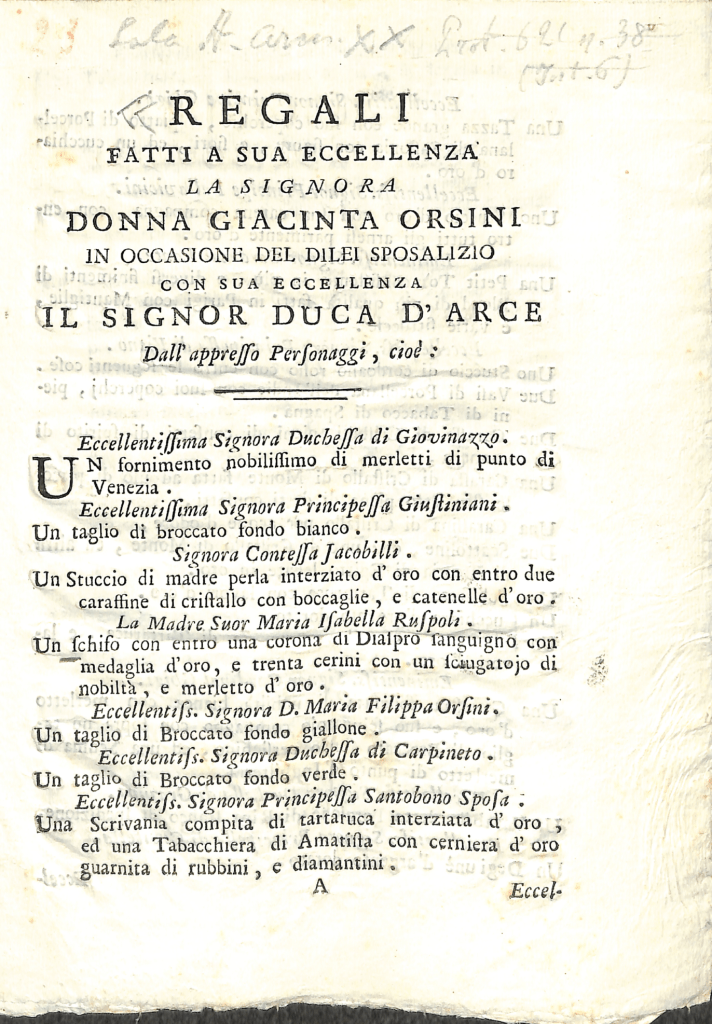

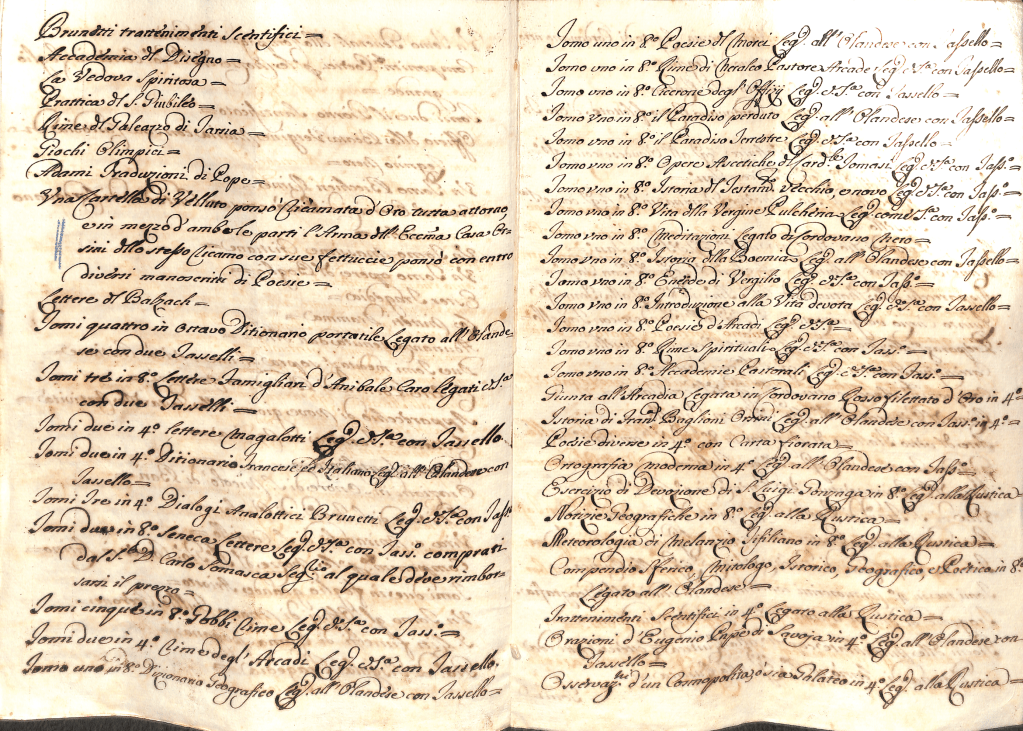

Published list of marriage gifts to Giacinta Orsini on the occasion of her 1757 marriage to Antonio (II) Boncompagni Ludovisi. Some of the gifts the couple received included (see bottom) “a desk with all its components made of tortoiseshell inlaid with gold, and an amethyst snuffbox with a gold hinge adorned with rubies and small diamonds.” Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

The painting below, by Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787), was likely created before Giacinta’s wedding, or meant to picture her before her marriage, showing audiences many facets of this extraordinary woman’s life. When auctioned in 1997, Christie’s described the painting as follows: “three-quarter-length, in a blue dress and pink ermine-lined cloak, holding a laurel wreath and a lyre, leaning on a pile of books on a clavichord, with a marble bust of Minerva, flowers and globe on her right, a classical landscape with Pegasus creating the fountain of Hippocrene on Mount Helicon beyond the volume[s] inscribed ‘IL PETRARCA’, ‘ANACREON and ‘TIT LIV HIST. Rom’, the score with the text ‘Vanne o Padre…’

Giacinta Orsini Boncompagni Ludovisi, Duchess of Arce, by Pompeo Batoni (1758). Private collection (auctioned 1997). Credit: https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-306136

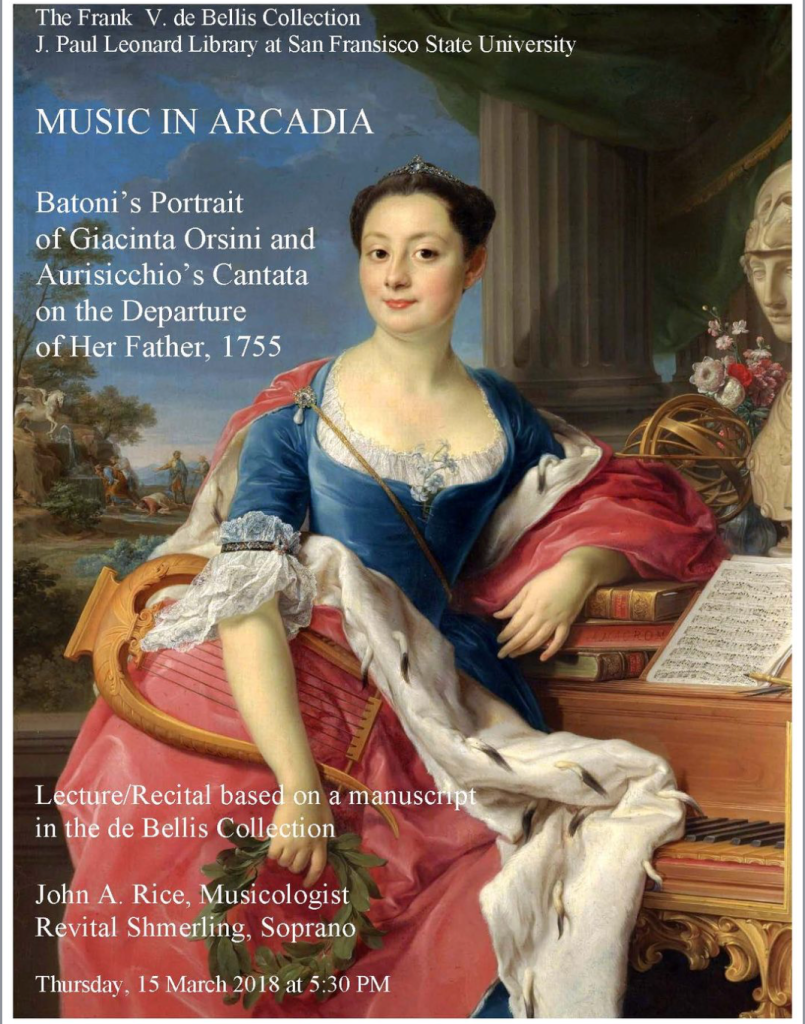

Giacinta is pictured holding a lyre and laurel crown, with an astrolabe, or globe, placed on the clavichord symbolizing astronomical interest. The Pegasus in the background further shows her association with the arts and poetry, as it links her to the Muses and the creative process. The presence of both the keyboard and the musical score with visible text highlights her musical talent and capacity as poet. In a 2018 article in the journal Early Music, the musicologist John A. Rice explains that the music is by the composer Antonio Aurisicchio (1710-1781) and the text by Giacinta herself. It is an aria ‘Vanne, o padre’ (“Go, Father”) performed in February 1755, on the occasion of Giacinta’s father Cardinal Domenico Orsini departing for a 10 month tour of his estates in southern Italy.

Unfortunately, despite her many talents and accomplishments, Giacinta’s life was cut short. She passed away in 1759 at the age of 17, during childbirth. Her firstborn son didn’t make it. She was buried in the family tomb at the Church of S Ignazio, with an inscription commemorating her life and virtues. The details of her funeral and burial are recorded in detail, as Emilie Puja has described on this site (see here, with also an image of Giacinta Orsini’s marker).

Partial list of Giacinta Orsini’s possessions at the time of her death, including a list of her books. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

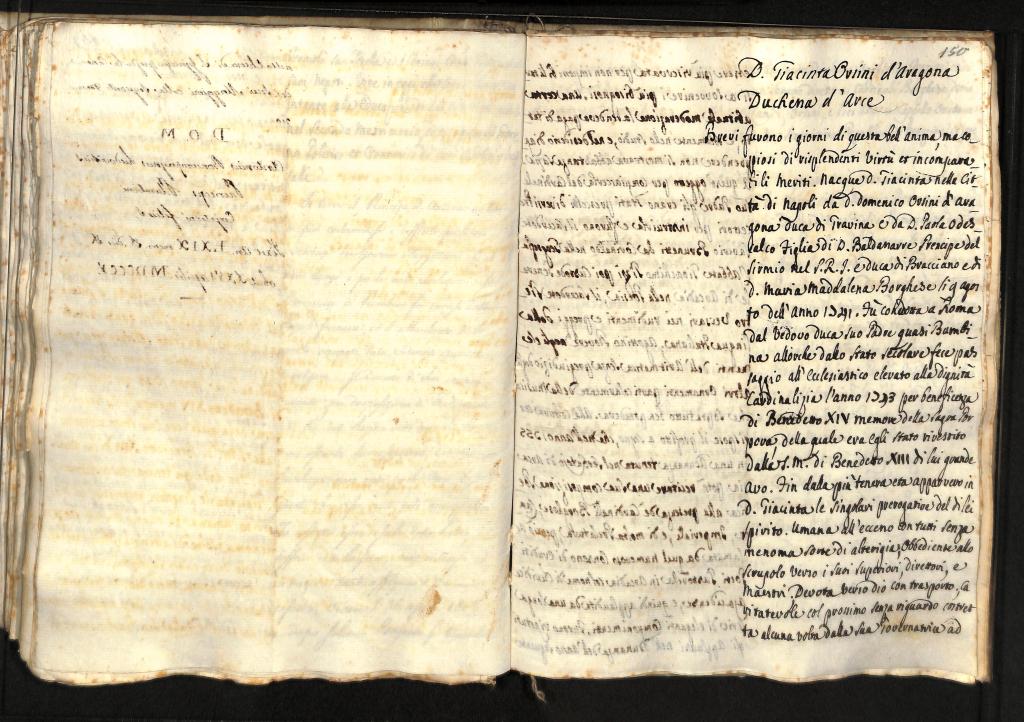

As Erin Rizzetto has explained in an article on Giacinta’s mother-in-law, Laura Chigi, the Boncompagni Ludovisi family maintained a book of obituaries with the long title Memorie genealogiche della Famiglia Boncompagni, con alcuni cenni della sua origine, e quindi unita alla Famiglia Ludovisi, fino alla generazione di D. Luigi Boncompagni Ludovisi, Principe di Piombino che morì il giorno 9 maggio 1841. The main author of the book was longtime family archivist Carlo Rosa alias Somasca (ca. 1718-1800), who served the Boncompagni Ludovisi from ca. 1760 until ca. 1795.

Giacinta’s biography is the longest one within Somasca’s collection. She will have died not long after the time the archivist started his work with the Boncompagni Ludovisi. He speaks highly of Giacinta, describing her as a quiet, kind, and respectful young lady who was passionate about her studies and her religion. Somasca also describes her as excelling in a variety of fields, such as music and poetic writing. He speaks of her marriage to Antonio Boncompagni Ludovisi in high regards, writing that they were a well-matched couple, and calling Giacinta a doting wife. Ultimately, Somasca makes it clear that her death was a tragedy to all who knew her, as Giacinta was loved by all for her aforementioned remarkable qualities.

What follows below are images of the Italian original of Somasca’s biography of Giacinta Orsini, with translated text. [I thank professor T. Corey Brennan for helping me with the transcription, and providing a translation. All images are courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi.]

150R D. Giacinta Orsini d’Aragona, Duchess of Arce. Short were the days of this beautiful soul, but glorious in resplendent virtues and incomparable merits. D. Giacinta was born in the city of Naples to D. Domenico Orsini d’Aragona, Duke of Gravina, and D. Paola Odescalco, daughter of D. Baldassare, Prince of Sirmio of the Holy Roman Empire, Duke of Bracciano, and D. Maria Maddalena Borghese, on 9 August 1741. She was taken to Rome by her widowed father, the Duke, when she was still almost a child. At that time, he moved from secular life to the ecclesiastical, elevated to the dignity of Cardinal in the year 1743 by the beneficence of Benedict XIV, mindful of the sacred purple he had received from His Holiness Benedict XIII, his [i.e., Domenico’s] great-uncle. From an early age, D. Giacinta exhibited the singular prerogatives of a gentle spirit. She was humane and kind to all without the slightest trace of arrogance, obedient to the point of scrupulousness towards her superiors, directors, and mentors. Devout towards God with fervor, charitable towards others without any compulsion or pretense.

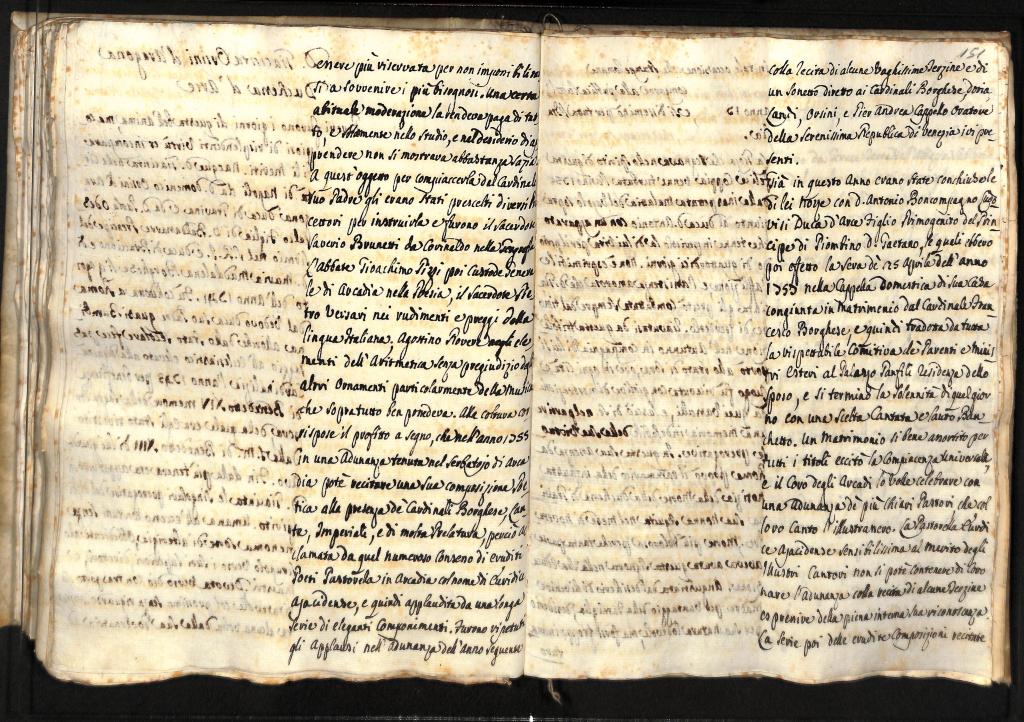

150V—151R She was more reserved by nature so as not to impose upon or disturb the most needy. A certain habitual moderation made her content with everything, and she showed no less fervor in study and in the desire to learn. To this end, her father the Cardinal selected several tutors to educate her, including the priest Saverio Brunetti from Corinaldo in geography, the abbot Gioachino Pizzi, later General Custodian of Arcadia, in poetry, the priest Pietro Versari in the rudiments and merits of the Italian language, and Agostino Rovere in the elements of arithmetic. These were without prejudice to the other accomplishments, particularly music, in which she especially excelled. Her education bore fruit, as in the year 1755, during a gathering at the ‘Serbatorio’ of Arcadia she was able to recite her own poetic composition in the presence of Cardinals Borghese, Lante, Imperiali, and many members of the clergy. She was therefore acclaimed by that numerous gathering of learned poets as a Shepherdess in Arcadia under the name Euridice Ajacidense, and subsequently applauded in a long series of elegant compositions. The applause was repeated in the following year’s gathering with the recitation of some charming terzine and a sonnet directed to the Cardinals Borghese, Doria, Landi, Orsini, and Pier Andrea Capello, Orator of the Most Serene Republic of Venice, who were present.

By this year, her marriage to D. Antonio Boncompagno Ludovisi, Duke of Arce, the eldest son of Prince of Piombino D. Gaetano, had already been arranged, and it was solemnized on the evening of 25 April 1757, in the family chapel of her house, officiated by Cardinal Francesco Borghese. She was then escorted by the entire respectable company of her relatives and foreign ministers to the Panfili Palace, her husband’s residence, and the day’s solemnity concluded with a select cantata and a sumptuous banquet. Such a well-matched marriage for all reasons excited universal approval, and the chorus of Arcadians wanted to celebrate it with a gathering of the most renowned Shepherds, who illustrated it with their songs. The Shepherdess Euridice Ajacidense, deeply moved by the merit of the illustrious singers, could not help but crown the gathering with the recitation of some terzine expressing her full inner gratitude. The series of learned compositions recited…

151V-152R …on that occasion, printed in Rome, came to public light in the year 17[–] and was disseminated throughout Italy.

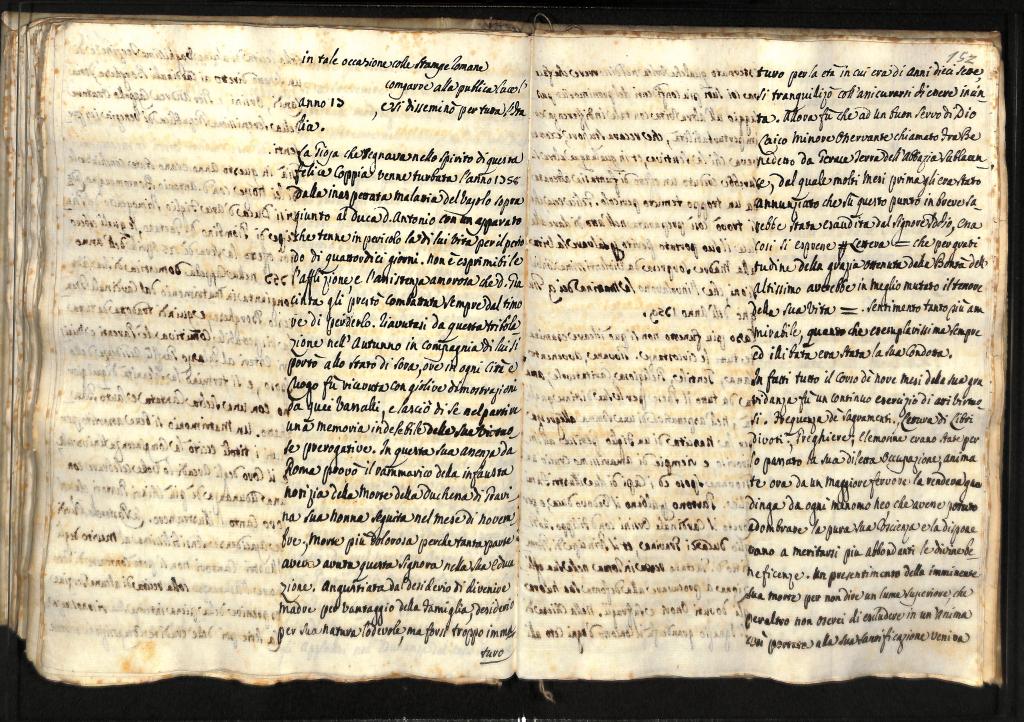

The joy that marked the spirit of this happy couple was troubled in 1758 by the unexpected illness that befell Duke D. Antonio, an illness so severe that it threatened his life for fourteen days. It is inexpressible the sorrow and loving care that D. Giacinta lavished upon him, constantly fearful of losing him. Recovering from this tribulation, she traveled with him in the autumn to the state of Sora, where in every city and place she was received with joyful demonstrations by the locals, leaving behind an indelible memory of her virtuous qualities. During this absence from Rome, she suffered the sorrow of the unfortunate news of the death of the Duchess of Gravina, her grandmother, in November, a death made more painful because this lady had played such a significant role in her upbringing. Anguished by the desire to become a mother for the benefit of the family—a desire praiseworthy by nature but perhaps too immature for her age of seventeen—she consoled herself with the hope of being pregnant. It was then that a good servant of God, a minor friar named Benedetto Riccio from Gerace, land of the Sublacensian Abbey, who had announced to her months earlier that this wish would soon be granted by the Lord, wrote to her expressing his gratitude for the grace obtained from the goodness of the Most High and resolved to change the course of her life for the better. This sentiment was all the more admirable since her conduct had always been exemplary and blameless.

Indeed, the entire course of her nine-month pregnancy was a continuous exercise of virtuous acts. Frequent reception of the sacraments, reading of devout books, prayers, and almsgiving had been her cherished occupation in the past, now animated by a greater fervor that kept her free from even the slightest stain that could have shadowed her pure conscience and prepared her to receive more abundant divine blessings. A presentiment of her imminent death, or rather a superior insight that we dare not exclude from a soul destined for sanctification,…

152V-152aR …was occasionally expressed in conversations with her closest confidants about her impending passage to the next life with such indifference and imperturbability that it astonished and moved those who heard her. In any other person, this would have been thought a product of a mind disturbed by excessive fear of danger. Happy she, who was thus prepared, at the moment of giving birth, to save the life of her son, was suddenly struck by violent convulsions that took her life on the morning of 9 June 1759.

No more tragic event can be imagined when all circumstances are considered. Young, attractive, healthy, gentle, religious, charitable, beloved by all for her distinctive qualities, in the expectation of great joy at the birth of a son, she perished suddenly and filled with bitter grief a young husband and the heads of two illustrious families. The widowed duke departed from Albano, while Cardinal Orsini, with D. Filippo his son, Duke of Gravina, and Prince D. Gaetano of Piombino, came to Rome in their affliction to procure the due honors and suffrages for their deceased daughter-in-law. In the Church of S Ignazio, there was a great attendance of all classes at the solemn funeral rites, after which she was buried in the family tomb, where the inscription reads:

D. O. M.

Here lies

Hyacintha Ursina de Aragonia

Daughter of Dominicus and Paula Odescalchi

Dukes of Gravina

First wife of Antonio Boncompagni Ludovisi

Died in childbirth together with her firstborn son

On 9 June 1759

At the age of seventeen years and ten months.

If the muses wept for the death of D. Vittoria Colonna, Marchioness of Pescara, they were not indifferent to that of D. Giacinta Orsini, Duchess of Arce. All the colonies of Arcadia in Italy made honorable mention of her, and the most fervent minds paid her the deserved praises. Rome, above all, wanted to distinguish itself by making the praises of that Euridice Ajacidense resound in the Parrasio Forest, who had illustrated it many times with her voice and presence. A public assembly was held, dedicated solely to the merit of the deceased Shepherdess. Small compensation…

152aV—153R …however, for the great loss that had been felt and for what more could have been expected from her if she had lived longer.

And indeed, what rare example was she not of every virtue? D. Giacinta, in the two years and few more months of marriage, was an example to all the ladies of her rank, and what lessons did she leave to those who had the fortune to know her, having made herself so sovereign in the hearts of all? With her family, she was loving and beneficent; with her husband, respectful and compliant; with her friends, sincere and grateful. In conversation, she was pleasant but reserved, and she loved above all else the retreat and private domestic company, often saying that she was ashamed to appear in large gatherings when in them she had nothing to envy in other ladies to make a worthy appearance. Indeed, from the common applause with which she was received and the satisfaction she brought with her discourse, even foreigners could not help but be impressed by her knowledge and the timely use of the French language. Yet this sentiment arose solely from a virtuous humility and a cautious desire not to expose herself too frequently to the scrutiny and pitfalls of the great world. It is not to be overlooked that when a knight approached to kiss her hand, she withdrew it in time and replied that he should rather kiss the feet of the Crucifix to implore His grace and not seek that of a miserable creature.

These and other truly Christian principles were the fruit of her continuous reading of holy and devout books, daily meditation and prayer, frequent use of the sacraments, and, in sum, the well-grounded acquisition of a praiseworthy devotion. Similar to the strong woman described in sacred scripture, though by inclination and her sharp insight inclined towards superior knowledge, she did not disdain to occupy some hours of the day in manual labor common to other women. And because she deemed the cultivation of poetry either too dissipating or too singular, she abandoned it, content to confine herself to the mere reading of history. No matter how many impulses she received to learn the rudiments of the Latin language solely to avoid being deprived of understanding the sacred scriptures, she could not be persuaded.

153V—154R When her husband was struck by illness in 1758, as mentioned above, what assistance did she not provide? What help did she not implore from heaven, with her vows and other prayers? How many tears did she not shed, determined in her distress to adhere strictly to the rule of S Teresa and fearing that any lack of correspondence to divine beneficences in the past would cause her to suffer the fatal blow of being widowed? Recovered from such a painful state with the healing of her husband, which undoubtedly had to be attributed to a special grace from the Most High, she expressed her due gratitude with both words and deeds, and after more than twenty days of domestic seclusion and care, she yielded to the persistent pleas of the convalescent Duke and was induced to breathe a more open air, moved more by the spiritual objective of the novena of S Joseph, which was being solemnized at that time, than by her health.

In such a course of life, the serenity of her spirit and her inner contentment—effects of a pure conscience—were so evident that they made her more lovable every day. Mature for heaven, it is no wonder that she was taken from this land of tears to enjoy the possession of eternal bliss in the prime of her youth. She was taken from us precisely so that, with the passing of the years, she might not be contaminated by human malice, in accordance with the wisdom of the Sage:

“He was taken up so that wickedness might not change his understanding.” [Wisdom 4:11]

Libretto of the Eumene of 1754, composed by Antonio Aurisicchio (1710-1781), with dedication to Giacinta Orsini, showing that she had been inducted into the Arcadians already in this year (at age 13), with literary name ‘Euridice Ajacidense’. Credit: HathiTrust

This biography by the Boncompagni Ludovisi archivist Carlo Rosa alias Somasca brings to light some never-before-seen information about Giacinta Orsini’s short life. Somasca writes in the first person, offering insights into her personality based directly on their relationship. One noteworthy fact he mentions is that Giacinta did not enjoy her Latin education, even though we know she wrote Latin poetry. The biography also explains how Giacinta secured a spot in the prestigious Academy of the Arcadians—though there is reason to think it happened in 1754, not 1755, as Somasca dates it. (See image above.) This biographical notice also clearly illustrates Giacinta’s intense religious devotion. Somasca mentions that Giacinta devoutly participated in the church’s sacraments during her pregnancy, regularly read scripture, and even gave up writing poetry to devote more time to reading history!

Though Giacinta Orsini is not a well-known figure, she should be recognized for her significant contributions to literature and the arts. Despite dying young, her literary accomplishments and the admiration she received from other poets highlight her remarkable talents. Her works were published before she could even turn 18, demonstrating her precocious ability and the lasting impact she had on those around her. This article, with these two unpublished 18th century accounts, paints a picture of her extraordinary life and talents, bringing Giacinta Orsini’s story to life in a way that deserves wider acknowledgment.

Flyer for a 2018 performance of Giacinta Orsini’s cantata “Vanne, o padre” and other pieces, with music by Antonio Aurisicchio, at San Francisco State University. A manuscript of the score is archived in the university’s Frank V. de Bellis Collection.

About the author: Sarah Freeman is a senior at the Morristown Beard School in Morristown, New Jersey. During the summer of 2024, she participated in the internship program at the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi. Sarah writes that she “had an amazing time uncovering more about the life of Princess Giacinta Orsini Boncompagni Ludovisi through my research. I am extremely grateful to HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for extending the amazing opportunity to work with primary documents in her archive, and to Dr. T. Corey Brennan at Rutgers University–New Brunswick for his endless guidance throughout the process, and for translating the transcriptions. I also give thanks to Nicole Freeto from the Morristown Beard School for inspiring me to study the rich history of Italy and Greece. I am honored to have worked on such a monumental project.”

VIDEO above: Opening of composer Antonio Aurisicchio’s aria ‘Vanne o padre’, for lyrics composed by Giacinta Orsini (1755). Reconstructed from John A. Rice,”Music in Arcadia: Batoni’s portrait of Giacinta Orsini and Aurisicchio’s cantata on the departure of her father “, Early Music 46 (2018) 615-630

Leave a comment