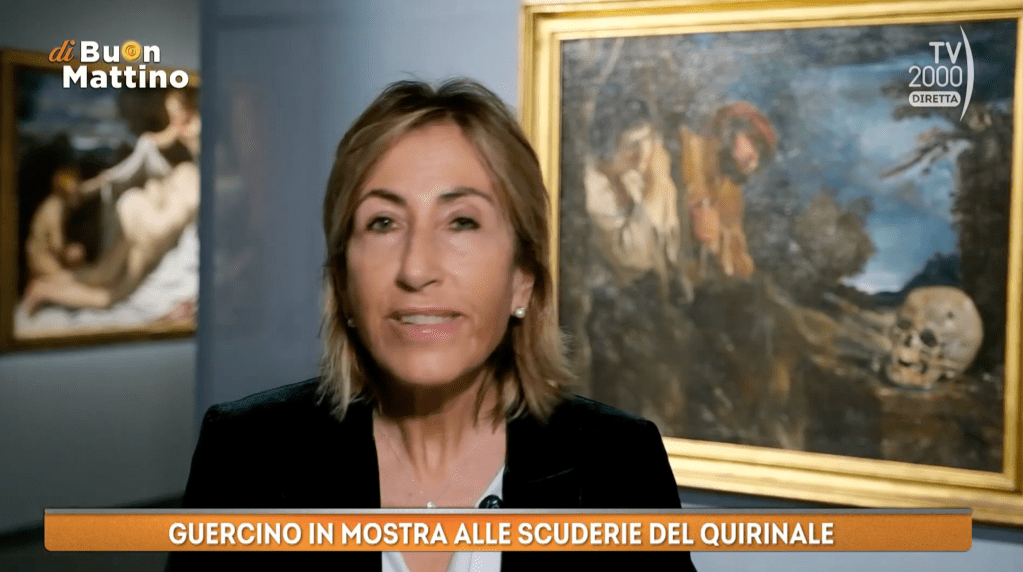

Well, this certainly was a welcome televised treat. On Italy’s long-running TV2000 morning show Di Buon Mattino, co-host Giacomo Cesare Avanzi featured the curators of “Guercino: L’era Ludovisi a Roma”: Raffaella Morselli (in the studio) and Caterina Volpi (in the exhibition gallery). Morselli and Volpi are respectively Professor and Associate Professor in Art History at University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’.

This blockbuster exhibition on the painter Giovanni Francesco Barbieri aka Guercino (Cento 1591-Bologna 1666), open since 31 October at the Scuderie del Quirinale, features over 120 works by or relevant to the artist, gathered from almost 70 collections. The show runs until Sunday 26 January 2025.

Here’s an attempt at a (slightly abbreviated) transcription with English translation of the TV2000 interview, that aired 3 December 2024, by ADBL editor T. Corey Brennan.

GIACOMO CESARE AVANZI: Good morning, Raffaella Morselli, art historian and curator of the exhibition Guercino: The Ludovisi Era in Rome! This exhibition, held at the Scuderie del Quirinale, is open until January 26. You will be able to see incredible works, which we will talk about now. One hundred and twenty two, correct?

RAFFAELLA MORSELLI: Yes, a large number.

GCA: Are they from various scattered museums?

RM: From all over the world: paintings, drawings, engravings, ancient sculptures, modern sculptures.

GCA: So, it’s a massive operation to collect and recover Guercino’s works. Let’s start with a portrait. Who was he?

RM: Guercino is one of the most famous painters of the entire 17th century. He has always been a beloved painter because he can communicate directly with the viewer. He was born in Cento, Emilia-Romagna, and he moved to Rome for just two years of his life, from 1621 to 1623, following a friend who became Pope Gregory XV (Alessandro Ludovisi) and his nephew, Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi. In Rome, Guercino carried out a stunning policy of visual representation for the Pope and the Cardinal Nephew. He left Rome upon the Pope’s death and never returned.

GCA: How did he learn art? How did he start painting?

RM: He was one of those young prodigies born with painting skills in their hands. Guercino constantly drew; he was an extraordinarily effective draftsman who thought with his pencil. There is an incredible number of his drawings, which reveal his early talent. He developed his skills between Bolognese and Emilian painting, ultimately becoming a 17th-century superstar.

GCA: And what were his favorite subjects? I imagine they evolved over his lifetime.

RM: Exactly. First of all, he was a deeply devout painter, focusing primarily on altarpiece painting in his region, especially inspired by Ludovico Carracci. Later, he also worked on nature studies, landscapes, and the connection between heaven and earth that became a hallmark of his lyrical style. Despite his modest lifestyle, Guercino was a painter that all of Europe wanted to commission. However, he chose to live in Cento.

GCA: We’ll [now] take you inside the Scuderie del Quirinale to discover some of Guercino’s most beautiful works.…Let’s view the exhibition and return to discuss it in the studio.

CATERINA VOLPI: We are in the room that illustrates the Ludovisi collection because the exhibition Guercino: The Ludovisi Era in Rome is actually an exhibition that contains within it several shows. It intertwines the paths of Guercino, his Pope, the Cardinal Nephew, and all the artists and figures who roamed Rome in the 1620s—a Rome that was truly the theater of the world, global, attracting everyone. And what did they gain? They learned from this short circuit between ancient sculpture, Venetian painting, and Guercino’s great art.

And what does this mean? It means that art in Rome would never be the same again. It would no longer be the classical art inspired by the myth of Raphael and Michelangelo, nor the tenebrist Rome of the Caravaggisti. Instead, it would become the Rome full of light, color, and Guercino’s joie de vivre, as well as the neo-Venetianism that elevated the central importance of Titian—something he had not previously attained in Roman culture.

The Ludovisi family brought Guercino to Rome. They promoted Domenichino, supported Guido Reni, and also introduced the scientific culture of the Accademia dei Lincei with Galileo Galilei. They welcomed literary figures like Giambattista Marino, who came to Rome from Paris when Gregory XV was elected Pope. Marino even summoned Nicolas Poussin from Paris, saying, “Come to Rome too.” When Poussin arrived, Gregory XV had passed away, but Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, the Pope’s nephew, was still alive and would remain so until 1632.

During these years, the Ludovisi collection became a sort of academy, a school of the world. Ludovico Ludovisi opened it up and shifted focus. He no longer concentrated solely on ecclesiastical politics, which had been Gregory XV’s priority—the global and planetary revitalization of the Church. Instead, he dedicated himself to the pleasures of villa life, patronage, banquets, theatrical performances, acquiring and decorating carriages. In short, his villa became a true center of worldly culture, a love of painting, aesthetics, and life itself.

GCA: Caterina Volpi, in her report, spoke about light and color, but there is also great compositional dynamism and a certain theatricality. So, there are many reasons to come and see the exhibition.

RM: The exhibition is surprising and leaves a lasting impression; one does not leave without a new perspective. This is because Guercino is empathetic—he speaks to us and pulls us into his works. Above all, the narrative of this exhibition takes us to a new scenario: this “theater of the world” between 1621 and 1623, where new ideas and thoughts are born, new saints are canonized—five saints in total. Foundations are laid for the Church of Sant’Ignazio and the Propaganda Fide, making this an exhibition that truly leaves its mark.

GCA: Let Guercino leave his mark on us. You brought three works to discuss—let’s start with the first, Aurora.

RM: Aurora is a ceiling decoration in the Ludovisi Casino, located within the Ludovisi vineyard. Guercino decorated it alongside others, and it never fails to amaze. Visitors can see it during the exhibition on Saturdays and Sundays, as an exceptional opportunity.

When Guercino arrived, the architecture had already been painted by Agostino Tassi, the most famous quadraturist in Rome at the time and a dominant figure in many projects. Guercino, an established painter from Cento, had to work with an existing architectural framework but created a wonderful story. The thunderous chariot of Aurora arrives to awaken the day, featuring the most felicitous horses in art history—marvelous workhorses, not racehorses. What does Guercino do? He boldly disrupts Tassi’s architecture, painting over it and transforming it into ruins, allowing his horses to pass through. There is a dual vanishing point leading toward the villa’s avenues, which existed at the time.

GCA: This Aurora, with her rosy-fingered dawn, brings us to consider the second work, which holds double significance because it is a Crucifixion. In the exhibition, it is displayed opposite another work by Guido Reni.

RM: This comparison was essential—it had never been done before. As a scholar of both Guido Reni and Guercino, it was always a dream of mine. It demonstrates how, by 1625—a Jubilee year—Pope Gregory XV had been preparing for the event. Unfortunately, he passed away in 1623, but everything he initiated was geared toward the 1625 Jubilee.

During this Jubilee, two altarpieces astonished viewers. The first was by Guido Reni for the Trinità dei Pellegrini in Rome. Guido, who was not in Rome at the time, was summoned by Cardinal Ludovisi to paint this incredible Crucifixion, which is part of the exhibition. Visitors can see it illuminated in an optimal way, presenting an Apollonian dream.

On the other hand, Guercino’s Crucifixion for the Basilica della Ghiara in Reggio Emilia was commissioned shortly after his return from Rome. It is a completely different composition, reflecting the Basilica’s importance at the time. Founded in 1598, this is the first time the Crucifixion has left the Basilica since 1625. Thus, Guido Reni and Guercino, painting at the same time—one in Cento and the other in Bologna—are displayed side by side for the first time.

Their approaches are completely different. Guercino’s work is naturalistic, filled with contrasts and dramatic scenes. In contrast, Guido’s work offers hope and a grand epiphany. We see two of the most beloved artists of the international 17th century, choosing different paths in the same year.

GCA: Was there contention between them, or was everything peaceful—thinking of the gossip of the era?

RM: The two did not like each other. Guido often claimed that Guercino had learned everything from him, including how to get paid. Guercino moved to Bologna after Guido’s death. There has been much mythology surrounding this. Guercino replaced Guido when he died. In reality, the War of Castro forced Guercino to leave Cento, coinciding with Guido’s death.

Certainly, there was no love lost between them. However, Guercino, fortunately, looked up to Guido Reni, who was older and had become an undisputed European master.

GCA: We are lucky to have these two magnificent works. Let’s move on to the third.

RM: This Moses has become somewhat the guiding painting of the exhibition. It is a small, quadro da stanza [i.e., domestic commission] but represents the latest discovery in Guercino’s catalog, making it an absolute novelty for the public.

The painting currently resides in England. It showcases all of Guercino’s skill in depicting Moses’s astonishment at the divine apparition. This piece was created for a Bolognese cardinal in 1624, so it was not commissioned for Cardinal d’Este or the Ludovisi family, yet it fits perfectly with the other works from this period.

Here, we’ve worked like entomologists, with a magnifying glass, focusing on the years between 1621 and 1624-25. We’ve cut across this period, examining the intellectual world circulating in Rome at the time, comparing everything that happened within this circle of thinkers led by Gregory XV—a pope who, though elderly, was highly knowledgeable and intelligent. He was particularly guided by his young cardinal nephew, Ludovico Ludovisi, who was the same age as Guercino.

GCA: We are accustomed to seeing portraits that depict anyone at any moment. Guercino’s extraordinary quality lies in his ability to speak to us contemporaries, and appeal to our sensibilities.

RM: Guercino speaks to us because we can identify with what he is narrating. In this Moses, we see the unfolding events—the surprise of Moses as he receives the tablets of the law, his astonishment, the epiphany of what is happening to him. Guercino tells a story; he is theatrical and not as distant as Guido, who becomes more synthetic, Apollonian, and somewhat harder to interpret. Instead, Guercino is there, waiting for us. This exhibition is waiting for you all—to amaze you.

GCA: The journey is not only a trip through art history but also an emotionally engaging experience.

RM: Yes, it is about wonder. You leave this exhibition filled with amazement, wonder, and so many new thoughts.

GCA: Our invitation is to visit the Scuderie del Quirinale by January 26. Thank you to Raffaella Morselli for coming to present this exhibition. Enjoy the exhibition, everyone!

Leave a comment