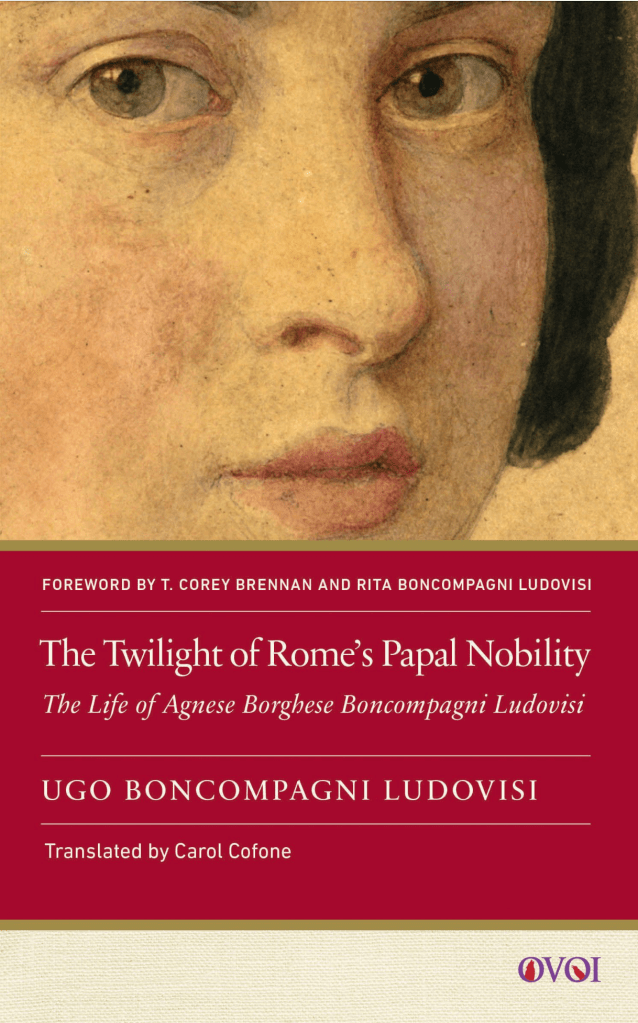

You do want to mark your calendar: on Tuesday 11 March 2025 Rutgers University Press, in its Other Voices of Italy series, publishes the first English translation of a century-old memoir still of stunning interest, The Twilight of Rome’s Papal Nobility.

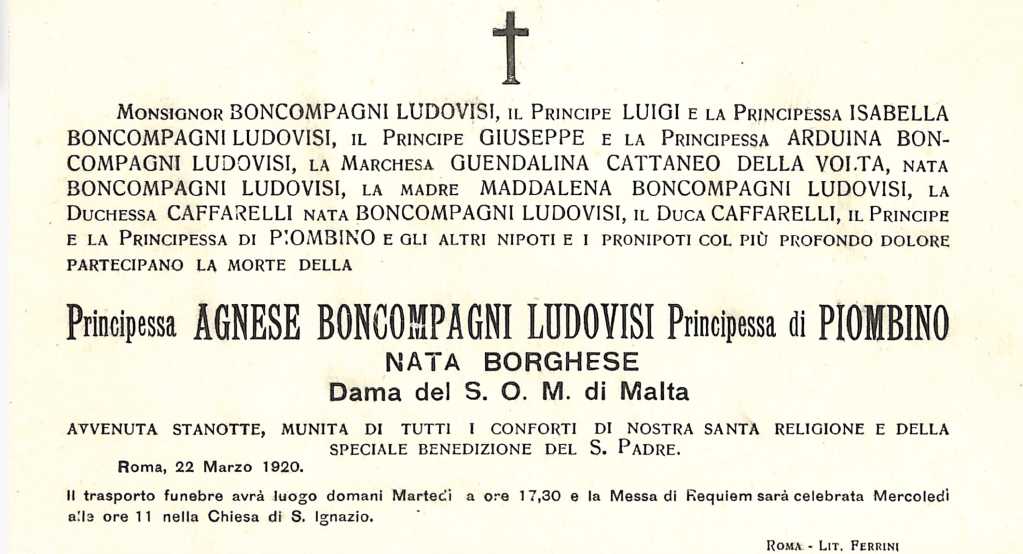

At its core, it details the life of Princess Agnese Borghese Boncompagni Ludovisi (1836-1920), a true matriarch in Roman noble society. Through birth and marriage, in her person Agnese united three of the most powerful papal households in Italian history: that of the Boncompagni (Gregory XIII, 1572-1585, of the Gregorian calendar), the Borghese (Paul V, 1605-1621), and Ludovisi (Gregory XV, 1621-1623). Over the course of her long life, she also directly experienced and processed political, societal and religious change of a sort that must once have seemed unimaginable.

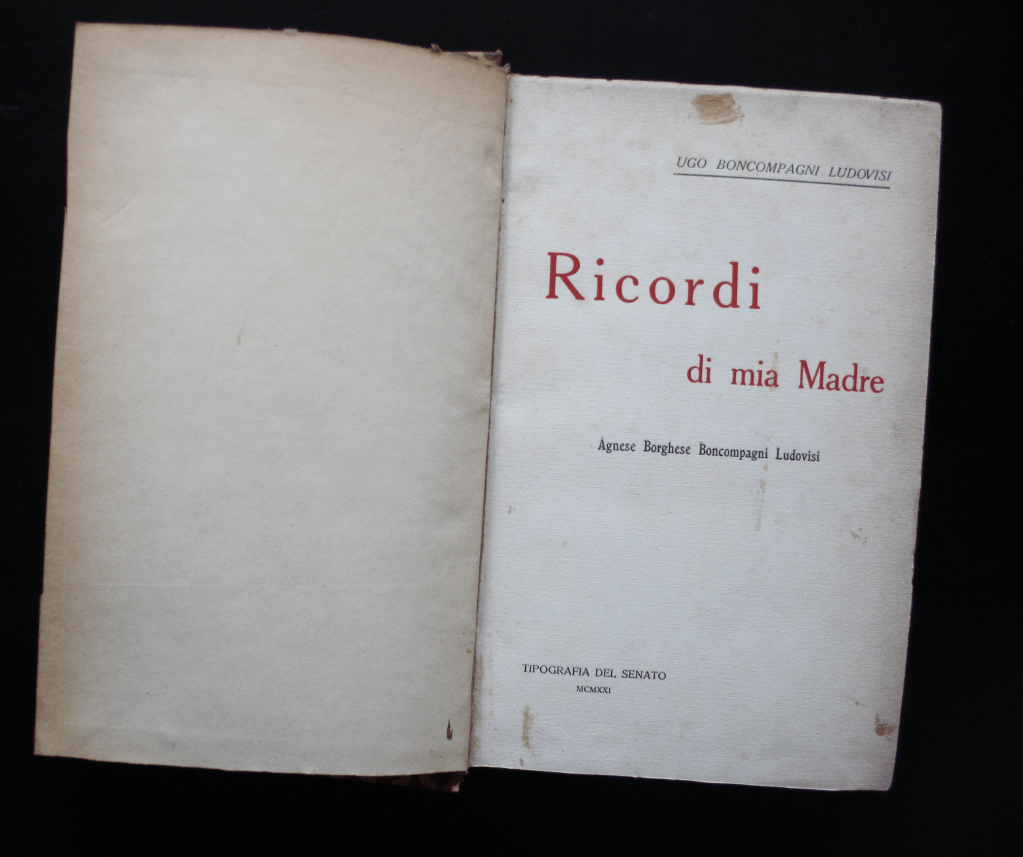

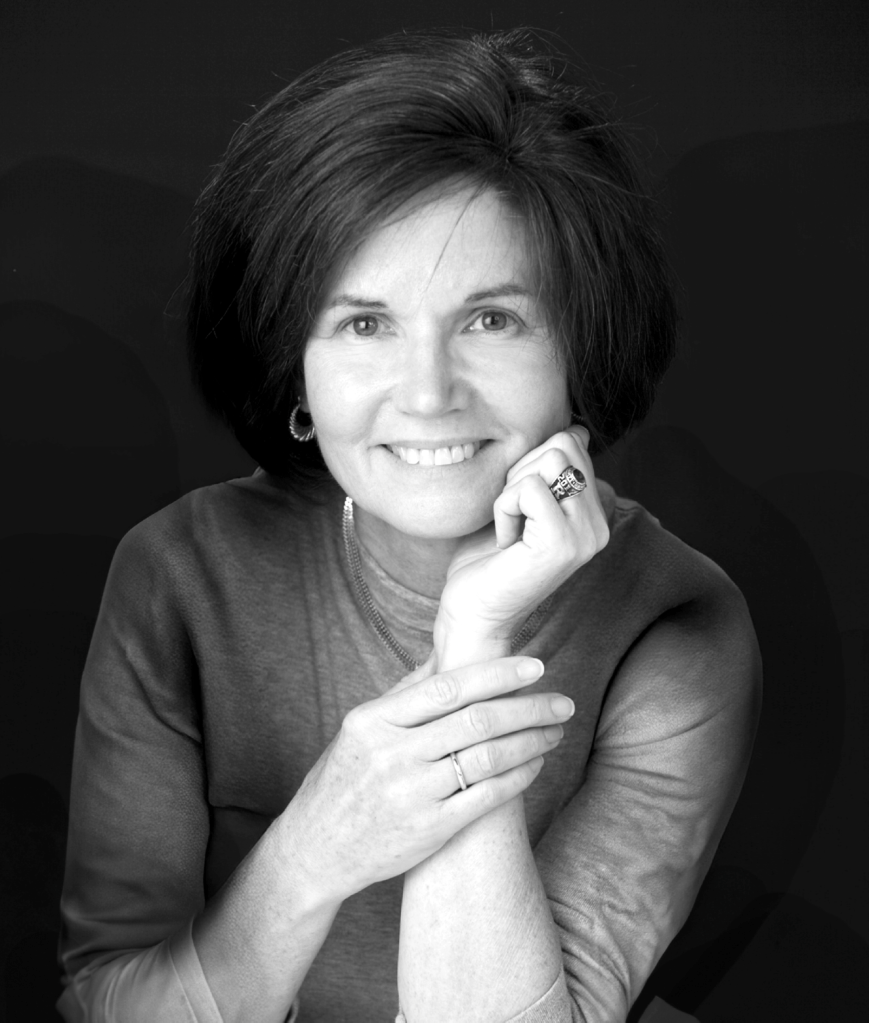

The book, written by Agnese’s eldest son Ugo and originally published in a 1921 limited edition as Ricordi di mia madre (Memories of My Mother), is translated by Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi [ADBL] assistant director Carol Cofone.

The volume comprehensively details Agnese’s unusually resilient career: her childhood (a poignant mix of privilege and tragedy), her marriage to Rodolfo Boncompagni Ludovisi, the careful raising of their six children, her deeply spiritual outlook and well-developed intellectual interests, her reaction (when in her mid-50s) to her family’s catastrophic financial disaster, and the brave journey of her final years. The memoir also amply covers Agnese’s public profile amid the tumultuous historical events that split the political sympathies of her own family, and decisively shaped the future not just of her social world but of her country. In the words of Carol Cofone, Twilight is “a memoir of nobility, loss and devotion” in 19th and early 20th century Rome.

The five children of Twilight author Ugo Boncompagni Ludovisi ca. 1903: from left (with Vittoria Patrizi, 1857-1883), Guendalina (Malvezzi, 1857-1951), Guglielmina (Campello, 1881-1973), and (with Laura Altieri, 1858-1892), Francesco (1886-1955), Eleonora (1885-1959, by 1904 a nun of the Sacred Heart) and Teresa (Giustiniani-Bandini, 1889-1969). Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

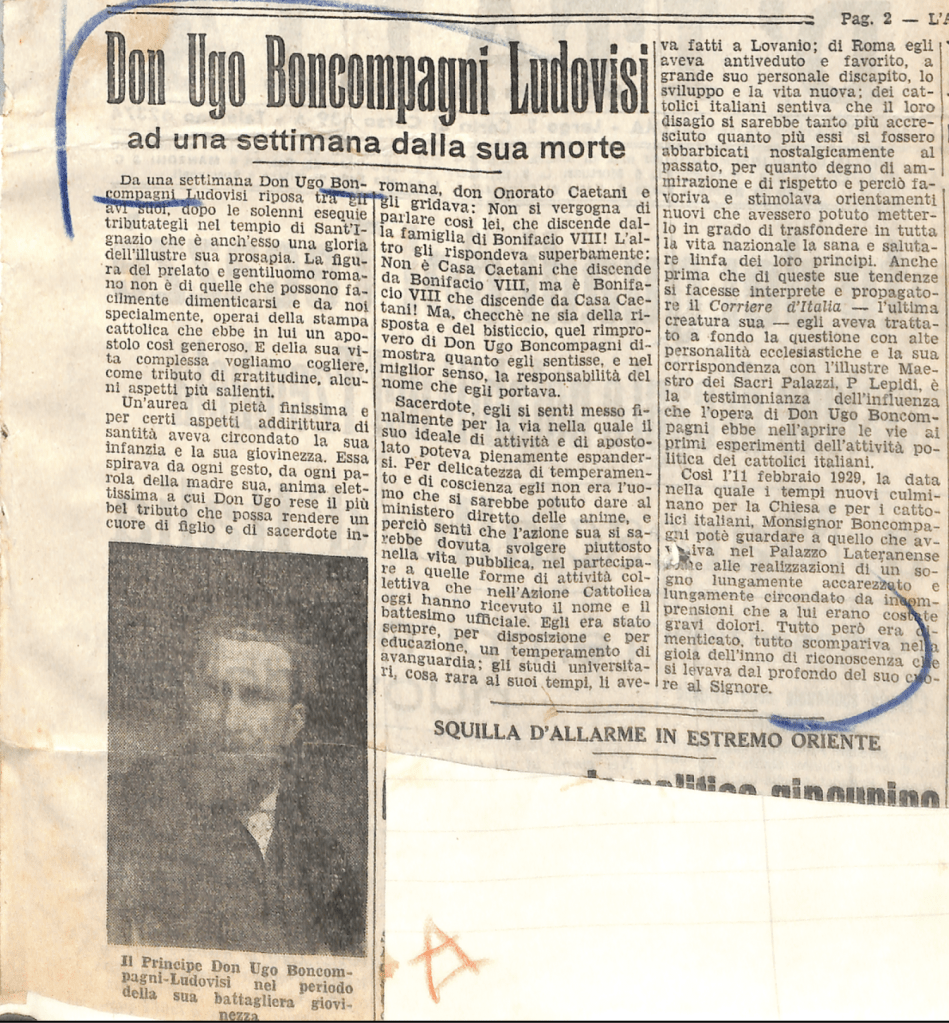

Agnese’s son Ugo Boncompagni Ludovisi (1856-1935) was a high-born Roman noble who—after losing two wives, who gave him five children—dramatically renounced his princely title and joined the priesthood, soon rising high in the Vatican. In this book’s pages, Ugo draws on his own memories, as well as diaries and letters written by Agnese, to give us insight into the years of the Italian risorgimento, when Italy finally achieved unification and, as a consequence, the Roman Catholic church lost much of its power. Ugo went on to write a half dozen other books, including a learned four volume history of Rome in the Renaissance (1928-1929).

Carol Cofone’s translation of Ugo’s work is its first-ever English edition, and it features prefaces from HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi and T. Corey Brennan. As the publisher rightly says, the volume “provides an invaluable first-person account of this history and culture in a story that is rich, complex, and increasingly relevant for today’s world”.

ADBL editor Corey Brennan sat down with Carol Cofone to ask her a few questions about this unusually impressive book—the result of a decade’s worth of work.

Four generations of Boncompagni Ludovisi at the Villa ‘La Quiete’ 20 October 1907. Standing behind center of bench (with hat) is Rodolfo Boncompagni Ludovisi, and seated at center is his wife Agnese Borghese, with granddaughter Maria Campello della Spina (1902-1987) on lap. Standing behind Agnese, in clerical garb, is her son Ugo. Also pictured: standing at far right, Ugo’s daughter (from first marriage) Guglielmina. Standing at far left, Ugo’s daughter (from second marriage) Teresa; sitting, on right of bench, his son Francesco, holding the hand of Guglielmina’s son Lanfranco Campello. Directly to the right of the boy is the family agent, Sig. Rocchi. Collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

C[orey] B[rennan]: What initially drew you to translating The Twilight of Rome’s Papal Nobility? Was it the historical significance, the literary style, or something more personal? Or did I twist your arm excessively?

C[arol] C[ofone]: Yes, you definitely twisted my arm! But that was essential. I never would have raised my hand to do this if it weren’t for your faith in my capability to see it through. The gradual, hands-on blog projects also boosted my confidence, despite my spoken Italian lagging behind my writing.

I think it was about 10 years ago–starting around 2015. I started doing a couple of small things, but really needing to work with Ugo’s text came in with some of those pieces. There were big passages from the book that explained how smaller episodes worked. Those preparatory articles acted as a guiding map, starting with the family’s 24 properties in Rome. That was astonishing to me. Another revealing episode was how Agnese and her husband celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary when they were still down on their luck, borrowing for a day a home they long had to rent out.

I also formed a fascination with their migrations, both forced and by choice, from Via della Scrofa in Rome to ‘La Quiete’ outside Foligno. They were like a trail of breadcrumbs. It gave me kind of an overview of the scope of this family’s footprint, literally and figuratively. So I think it was very encouraging that I could tackle those projects and really get involved in what Ugo was trying to tell us. Because he’s the master of indirection. He hints at major historical shifts without overt declarations. He just mentions them inpassing. He does not rant; he was much too well raised for that. That subtleness has made the challenge of translating and understanding Ugo’s memoir so rewarding for me.

I should say that the original Italian text of Ugo’s book is exceedingly rare—there’s only thirteen libraries worldwide that have it. Although a digital scan is readily available on HathiTrust, it’s just not a reader-friendly medium for me. Kudos here to Sherry Gerstein’s exceptional pre-production work for Rutgers University Press to make the printed edition such a beautifully designed book. So I think that English speakers—and many Italian speakers are also English speakers—may see this text in a whole new way by virtue of the fact that it’s so well designed.

1921 edition of Ugo Boncompagni Ludovisi, Ricordi di mia Madre, published by the Tipografia del Senato (Rome). Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

CB: You mention “hearing voices” while translating the book. How did Ugo and Agnese’s voices influence your approach to the translation?

CC: I really did hear their voices during the process. Reading the original Italian, I could see that Ugo had a formal style, as a member of a privileged group, the elite. And Agnese was a real polyglot, and was always attending to how perfectly he spoke or didn’t speak—not just in Italian. In some of the letters Ugo exchanged with his mother, it was obvious that she habitually corrected his French. I wanted to honor that, and although it is not the usual practice, because most translators strive to bring the text into the idiom of the reader. I have to thank Sandra Waters and Eilis Kierans, the editors at the OVOI imprint, and Carah Naseem, Twilight’s editor at Rutgers University Press, for their expert guidance in this.

As a result, I think Twilight preserves the traditional feeling of the communication of this Roman noble Papal family. They took their purpose, their role in the world, super-seriously. They were citizens of the world and they believed in the importance of that. I think the big story here, when it all came apart and Ugo ends up renouncing his title, passing it to his son: these were really, really difficult things for this family to do. It challenged their view of their place in the world, the strata of society that they occupied, even their view of their religion. And the fact that they really soldiered on.

In the last chapter of the book, Ugo talks in depth about Agnese’s activities after she was a widow and how she was fully engaged to the degree that her physical capabilities permitted. And I think they all had a strong sense of duty and purpose, as well as a strong and deep abiding connection to all these different European cultures. And maybe this was the last time in history that this was going to be that strongly felt.

Obituary of Ugo Boncompagni Ludovisi in L’Avvenire d’Italia—Roma (17 Nov. 1935). Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

CB: One notable thing about this memoir is that the narrative plunges you right into a whirlwind of history…

CC: Talk about getting dropped into the action, I mean, in the very first chapter! It’s the revolutionary year 1848, and Agnese’s father is trying to quell protests in the street. And then Pellegrino Rossi is assassinated and Pope Pius IX has to escape from Rome. And so they follow him and Agnese is giving us a play by play. And she’s 12 years old. And so I think she was wise beyond her years, old beyond her time. She was more accomplished than some of the other members of the nobility, who were maybe a little more dilettantish.

You can safely say that, because there are several sections where Ugo recounts what was on his mother’s reading list, and the fact that she annotated all her books, she was well-informed. She was forthright in ways that I don’t think many women were at that period of time, and she knew what she was talking about—and she knew what she didn’t want to talk about. Plus there’s the “Who’s Who” of people that were in her family tree. Ugo drops in passing that Agnese’s great-great-grandmother was Napoleon’s sister.

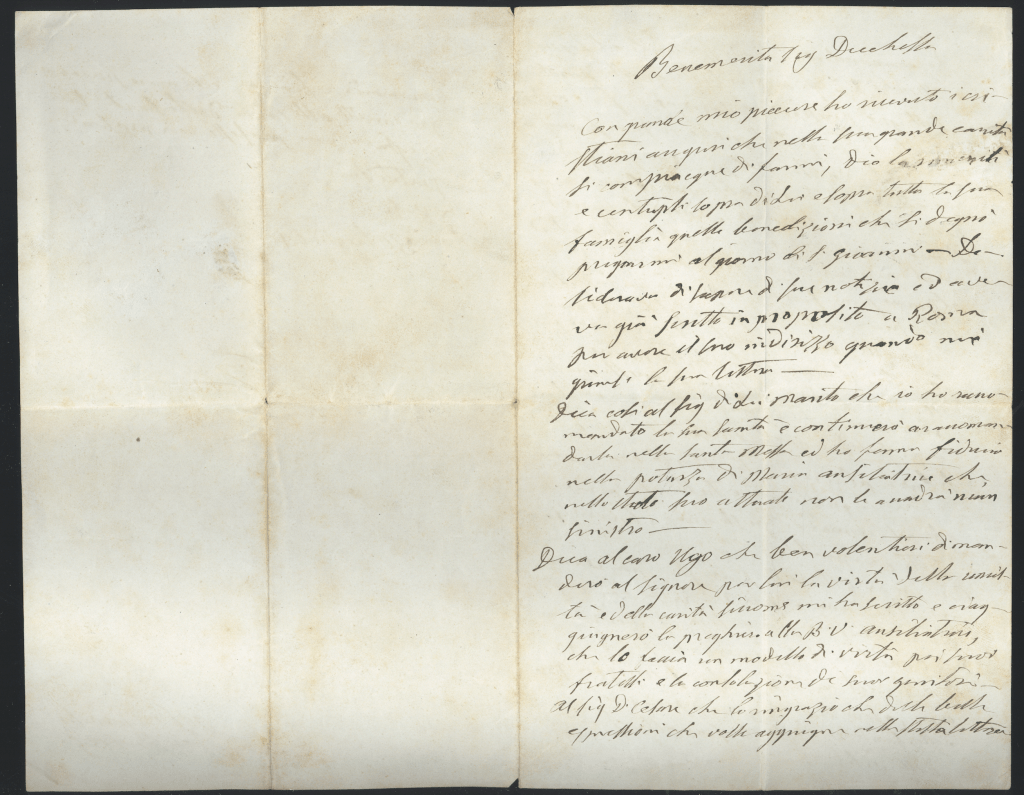

First page of letter (30 July 1867) from St Don Bosco to Agnese Borghese Boncompagni Ludovisi. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

CB: Tell me about your decision process in to editing the many personal letters preserved in Twilight.

CC: That largely came down to the book’s sheer volume. I mean, the original is over 450 pages. I really didn’t want to do violence to the text, and so I looked for places where I could take out a big chunk that didn’t take away the continuity. I did exclude many of Agnese’s philosophical “encyclicals” to her sons, where she is offering moral guidance or educational advice, as they didn’t contribute new narrative content. Similarly, I omitted letters which Agnese exchanged with religious figures, as they were not essential to the central story. Many clerics were cultivating relationships with his family because I think they got a lot of financial support when they did.

Though I translated all these letters, they didn’t make the final cut. Yet they still exist for those who might need them in future research—and should be particularly valuable for organizing this material in the Boncompagni Ludovisi family archive.

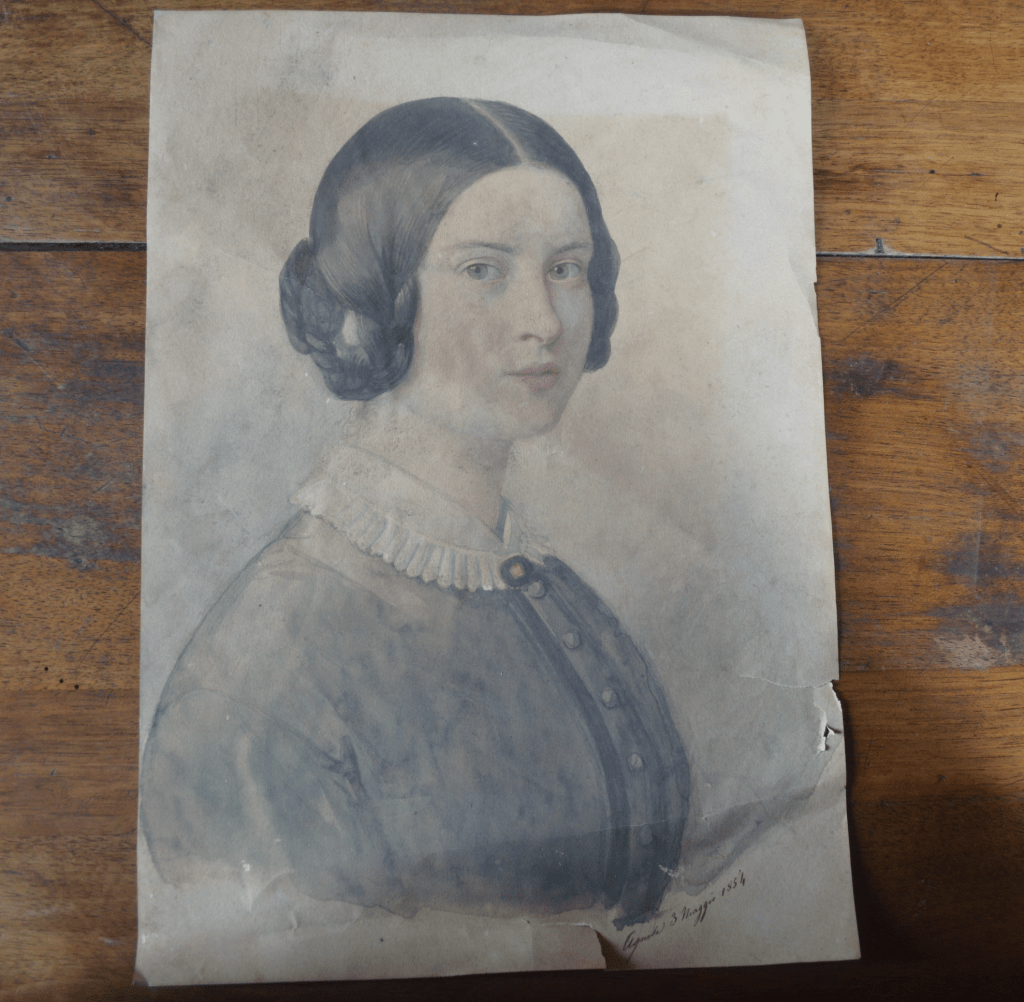

Carol Cofone identified this 3 May 1854 depiction of Agnese Borghese (discovered February 2016) as a self-portrait, drawn shortly before her 31 May 1854 marriage to Rodolfo Boncompagni Ludovisi. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

CB: Did the discovery of Agnese’s self-portrait in 2016 help shape your understanding of her?

CC: It was so important. I was fascinated by your account of how you discovered it in deep storage in an unlikely spot at the Casino dell’Aurora. Seeing her image, captured right before her [1854] marriage, which is so expressive, much more so than any photo ever taken of her, made me feel like I knew her better. And then when Ugo refers in the book to the very same portrait as a self-portrait, it felt like one of those moments when you connect with a historical figure in a much more meaningful way. It’s like seeing her face for the first time, and it connected me with her artistic spirit. I think this was Agnese indicating what image she wanted for the cover!

We have some uncomplimentary watercolor caricatures of Agnese as a younger woman. And I’ve seen other accounts in other books where she’s called Saintly Agnese. So I think she was kind of viewed socially, as awkward, not fashionable. Ugo talks about how she didn’t even want to wear her trousseau. She certainly skipped the high-society theatrics typical of that time.

Ugo has interesting things to say about how Agnese thought about her marriage. For her, Rodolfo Boncompagni Ludovisi was the only real choice for her because he came forward and said how he felt about her. He wasn’t afraid to risk rejection. And in doing so, he was recognizing a person of quality. He had a greater understanding than others of the qualities that made her exceptional. I think her marriage with Rodolfo remained very strong–through thick and thin, and even thinner.

Satirical portrait of Agnese Borghese Boncompagni Ludovisi by Filippo Caetani (before 1864). Credit: G. Gorgone and C. Cannelli (edd.), Il salotto delle caricature: Acquarelli di Filippo Caetani, 1830-1860 (Rome 1999).

CB: Can you say a bit about Ugo’s presentation of himself in this book, especially as family fortunes dipped?

CC: Ugo was widowered twice. He was the father of five. As the oldest son, he was raised to assume the title of the Prince of Piombino. However, he set aside all these roles to enter the priesthood, ultimately assuming the role of vice-camerlengo at the Vatican. I feel this was a result of the reversal of family fortunes, for which he blamed himself. He says this explicitly in the book.

I was hooked on the book from Ugo’s first phrase: “To my few readers”. You know, every writer in the world is sitting there at a table talking to themselves when they start. But with these words, you understand what he thought his role as author was. He really meant this book to be for his inner circle. Ugo never thought he would have modern readers. Well, more than a century later, I hope he will have many.

In that very first introduction he also says—I’m paraphrasing—”I realize that far too often I’ve mentioned myself”, but he mentions not only himself but his siblings, his children, Agnese’s siblings, Agnese’s father…I don’t think he mentioned himself inordinately compared to the full display that he’s created of so many family members and interesting people who factored in their lives. It also points out to me a lot of things that I still don’t know. This book rewards re-reading, even for me.

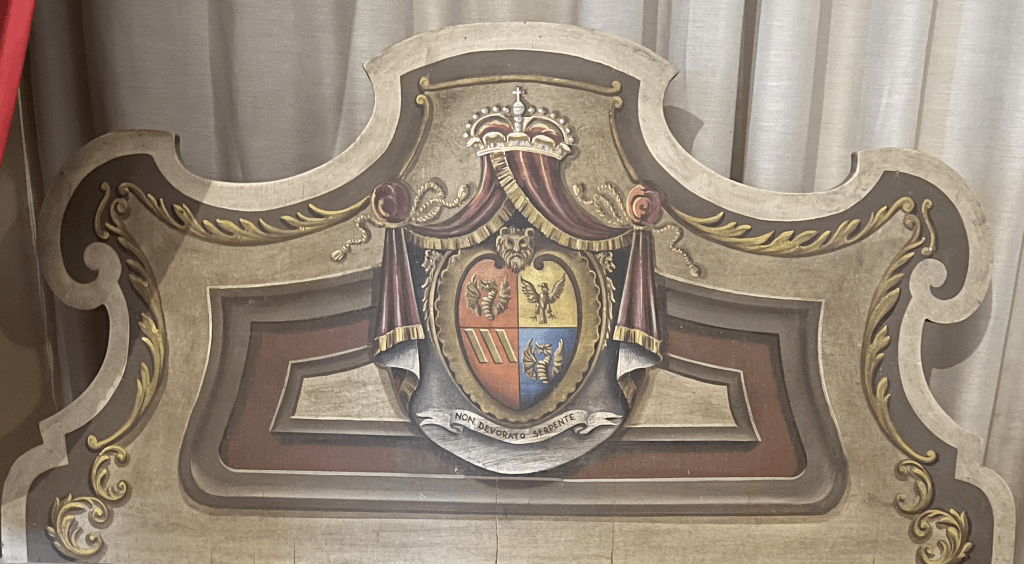

Bench commemorating the marriage (1854) of Rodolfo Boncompagni Ludovisi and Agnese Borghese, with joint arms of each family. Probably commissioned by Agnese in 1890 for the Palazzo Piombino in Via Veneto (now US Embassy in Rome); currently in the vestibule of the Casino dell’Aurora, Rome.

CB: You describe Twilight as “nearly ethnographic.” How does the book serve as ahistorical document beyond being a personal memoir?

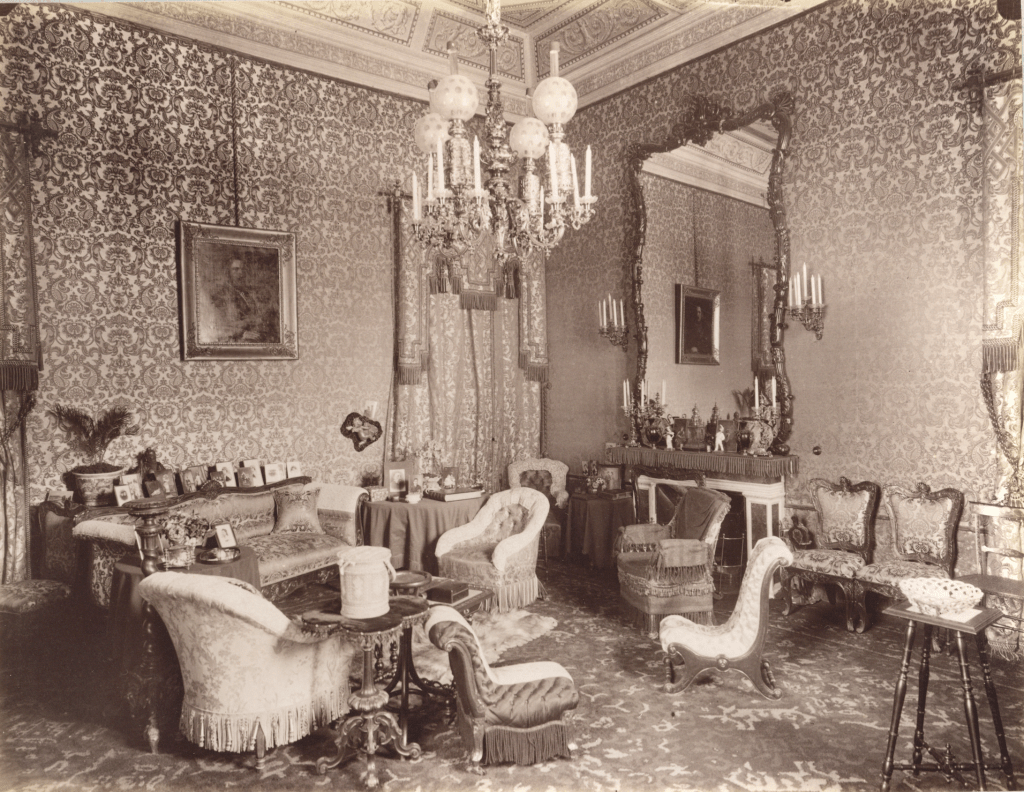

CC: The book, in its effort to center Agnese’s role as wife and mother, shares a great amount of detail about the family’s day to day life. There are few records this explicit about matters of the family’s religious observances—like Christmas masses, household management—how the servants were fed, travel—their summer home in Foligno, education— home schooling in Foligno , births and deaths—so many of them, social engagements—Agnese’s salon in Via della Scrofa. I love that! The truth is that this way of life no longer exists, so this book which preserves this part of Italy’s cultural heritage is the best way to imagine it.

On the other hand, though these events mark the end of an era, in terms of one family’s saga, they also tell a new nation’s story. What is remarkable to me is that the saga and the story are still being told. What becomes of the Casino dell’Aurora, the last building of the original estate still in family hands, is a chapter in the history of the family and the nation that is still to be written.

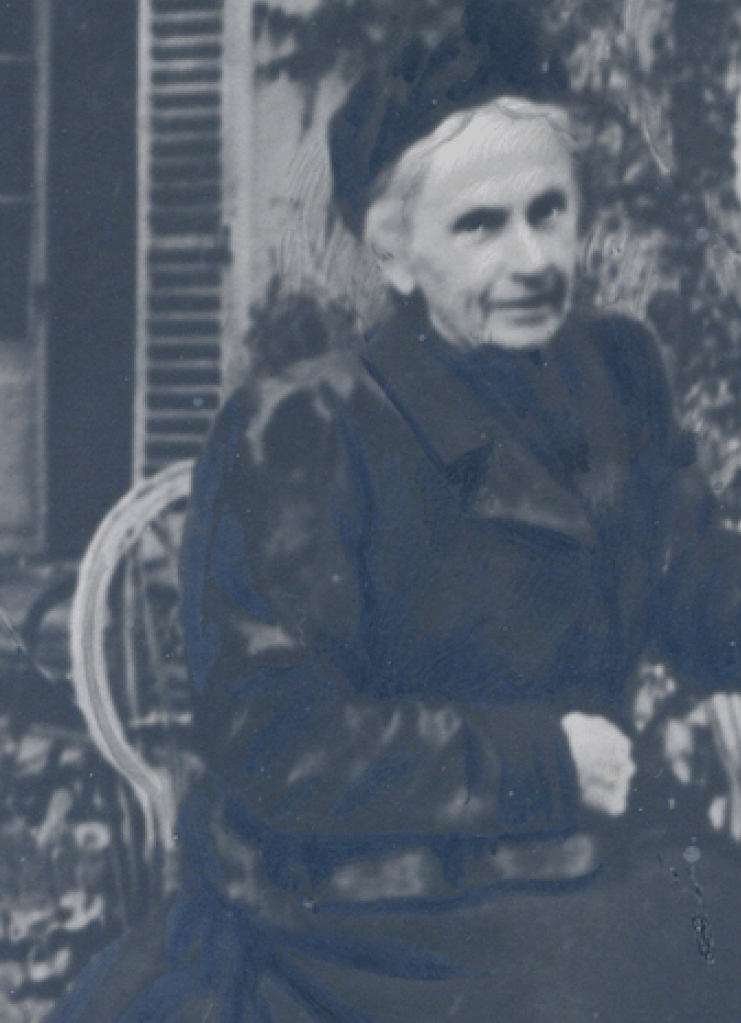

Agnese Borghese Boncompagni Ludovisi, Princess of Piombino, ca. 1910, presumably at ‘La Quiete’ near Foligno. Collection †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

CB: How does Ugo’s account help contemporary readers understand the broader social and economic shifts of his life and times? And what does it tell us for our times?

CC: Ugo is telling the story of how the Unification of Italy, and the establishment of Rome as its capital, changed everything for the Roman nobility. The financial foundation of this entire strata of society was undermined, first by the impact of the Napoleonic Code, which prevented the practice of primogeniture so that family fortunes could not readily be preserved generation to generation. Then, the efforts of the comune of Rome to modernize the city resulted in a lot of taking of property, long held by the nobility.

But their urban plans did not pan out—the real estate market bubble burst when the actual demand did not meet expectations. Finally, the nascent Italian banking industry collapsed in the face of these economic headwinds. So much of the story finds parallels in our own times: economic collapses, banking crises, drastic shifts in power and social norms. Maybe the truism that this book reveals, and that holds for all times, is that things never go as planned, but they go as you probably should have expected.

These are all very much current issues—like who holds power, who doesn’t hold power, who has a right to be here, who doesn’t have a right to be here. Like William Faulkner said, “The past is never dead. It isn’t even past.” So I am a beneficiary of Italy’s historical upheaval of society. Had I lived in an earlier time, I wouldn’t have been able to walk in front of the ex-Boncompagni Ludovisi palace that’s now the American embassy, which I very happily did many times.

Private sala of Agnese Borghese Boncompagni Ludovisi in the Palazzo Piombino al Corso, Rome (demolished 1889). The portrait at left on the wall is of her father Marcantonio (V) Borghese, Prince of Sulmona (1814-1886). Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

CB: Ugo intertwines his mother’s story with his own life. How does his personal narrative affect the portrayal of Agnese?

CC: Ugo’s status as oldest son made his relationship with his mother of special importance.This likely would have been true in most other Roman noble families. But the mother/son relationship was even stronger for Agnese and Ugo because Agnese lost her mother at an early age, and felt a bit left out among the second family her father raised with his second wife, Thérèse de La Rochefoucauld. Much of her own identity was invested in Ugo. That is why when he renounced his title and it passed to his son, Francesco Boncompagni Ludovisi, it had an impact on both Ugo’s—and Agnese’s—sense of purpose in this life.

But also, you know, in modern times, we are such avid royal watchers. I remember getting up at dawn to watch the wedding of Charles and Diana. And anything that Prince Harry does makes the headlines; his memoir was a bestseller on Amazon. Yes, I’m biased, but I think Ugo’s memoir is better than Prince Harry’s.

That said, Ugo seems very, very old fashioned to us because he keeps elevating the role of Agnese as wife and mother, though very few women are princesses in two astonishingly powerful families. But that I think is just totally consistent with how women were viewed at that time. And that’s how he honored his mother, writing for a very tight circle.

Death notice of Agnese Borghese Boncompagni Ludovisi (22 March 1920). Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

CB: I love the fact that Ugo founded a winery in Umbria. He doesn’t talk much about it in the book.

CC: No, he doesn’t, though Scacciadiavoli was very important to him. In fact, the large Case Vecchie property the family owned in Umbria was important to them all. I’m sure it was difficult for Ugo when he had to sell the winery to satisfy debts, when things were all sliding sideways.

Scacciadiavoli is historically important because when Ugo created an innovative French-style winery there, it became a technological model for the Umbrian wine industry. The winery still exists today and is thriving! It’s owned by the Pambuffetti family, who are direct descendants of one of Ugo’s employees.

Ugo may have inherited his love of viniculture from his father. He tells us that Rodolfo planted a beautiful vineyard at their home in Foligno. Ironically, Agnese was a teetotaler. Nonetheless, she believed Rodolfo’s wine, Renaro, had medicinal properties. So when anyone was experiencing any malady, she would send a bottle of it to them.

CB: How does it feel to see Twilight finally published?

CC: First and foremost I am thrilled that it has become a reality. I owe this great experience to so many people: my brilliant professors in the Rutgers Italian Department, especially Alessandro Vettori and Andrea Baldi; everyone who has been part of Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi during the past decade; but most of all Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi and you, Professor Brennan, who made all this possible. It has been a wonderful adventure. I am a little wistful, too. With Twilight being in print, it feels like the end of a chapter. Let’s get a bottle of Scacciadiavoli, and make a toast to whatever comes next.

Carol Cofone is a writer and researcher with experience in publishing, translation, and public outreach for urban planning; for the past four years she has served as assistant director of the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi. Carol is the translator of The Twilight of Rome’s Papal Nobility (2025), and a contributor to Rutgers Then and Now (2024), which tells the story in words and pictures of Rutgers’ evolution over more than two and a half centuries. She helps preservationists, urban planners and cultural institutions see things in a new way—or an old way – so they can change everything—or keep it all the same.

Leave a comment