Nicoletta Boncompagni Ludovisi, Princess of Piombino (press photograph, 17 February 1928). Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

By Isha Gullapalli (Rutgers ’27)

The date is 3 March 1929, more than six years into Benito Mussolini’s Fascist regime. Three weeks previous, the Lateran Accords have been signed, finally settling the question of how the Kingdom of Italy and the Papacy will share power in light of Italy’s 1870 unification. With this compact, Vatican City has been created, with the Holy See given full jurisdiction over this new state. And Arnaldo Cortesi, the New York Times’ foreign correspondent to Rome, has just published an article shining an international spotlight on Princess Nicoletta Boncompagni Ludovisi.

The article in question puts Princess Nicoletta at the forefront of a conservative movement, encouraging Italian women to abandon trendy Parisian fashions and embrace Italian clothing and designers. But who exactly is Nicoletta, and what does she have to do with Italian fashion?

Portrait of Nicoletta Boncompagni Ludovisi, Princess of Piombino, in Rome’s Casino dell’Aurora, by Carlo Siviero (1882-1953). Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

Princess Nicoletta Boncompagni Ludovisi was born Nicoletta Prinetti Castelletti in Merate (just west of Bergamo in Lombardia) on 19 March 1891. Her father was Marchese Giulio Prinetti (1851-1908), a key manufacturer (including of early motorized vehicles) and conservative politician who would be Minister of Public Works (1897-1901) and then Secretary of State (1901-1903) under King Vittorio Emanuele III. Her mother was the Marchesa Francesca d’Adda Salvaterra (1860-1920), descended from both French and Italian nobility. Nicoletta had two younger twin sisters, Maria and Maddelena (b. 1895), who died in infancy.

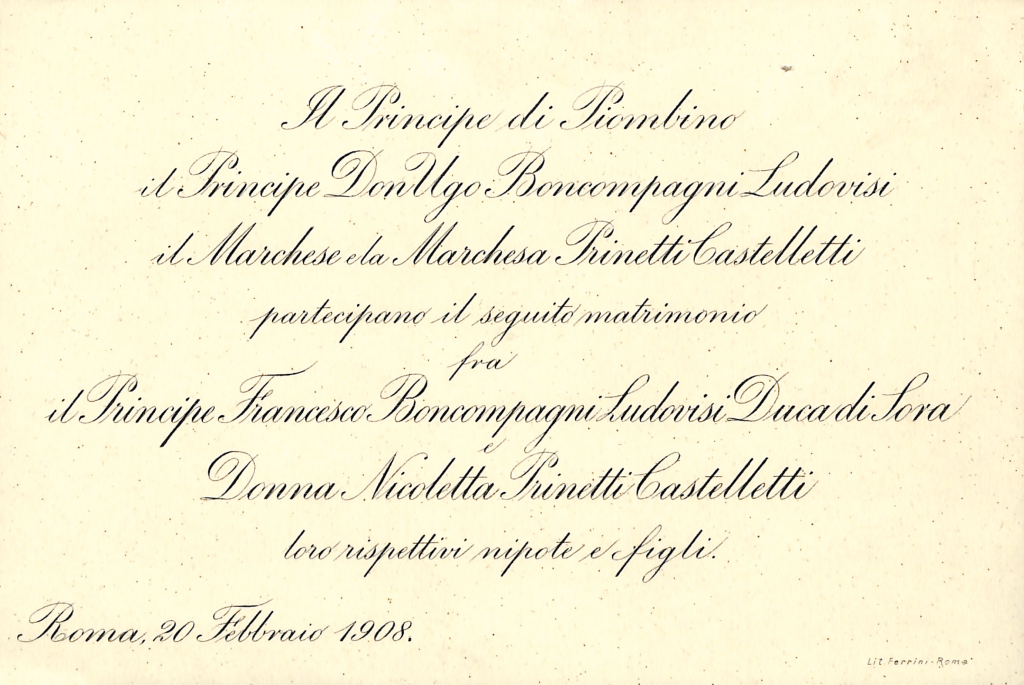

Joint announcement by Princes Rodolfo and (his son) Ugo Boncompagni Ludovisi and the Marchese and Marchesa Prinetti Castelletti heralding the upcoming wedding between Ugo’s son Francesco and Nicoletta Prinetti Castelletti. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi

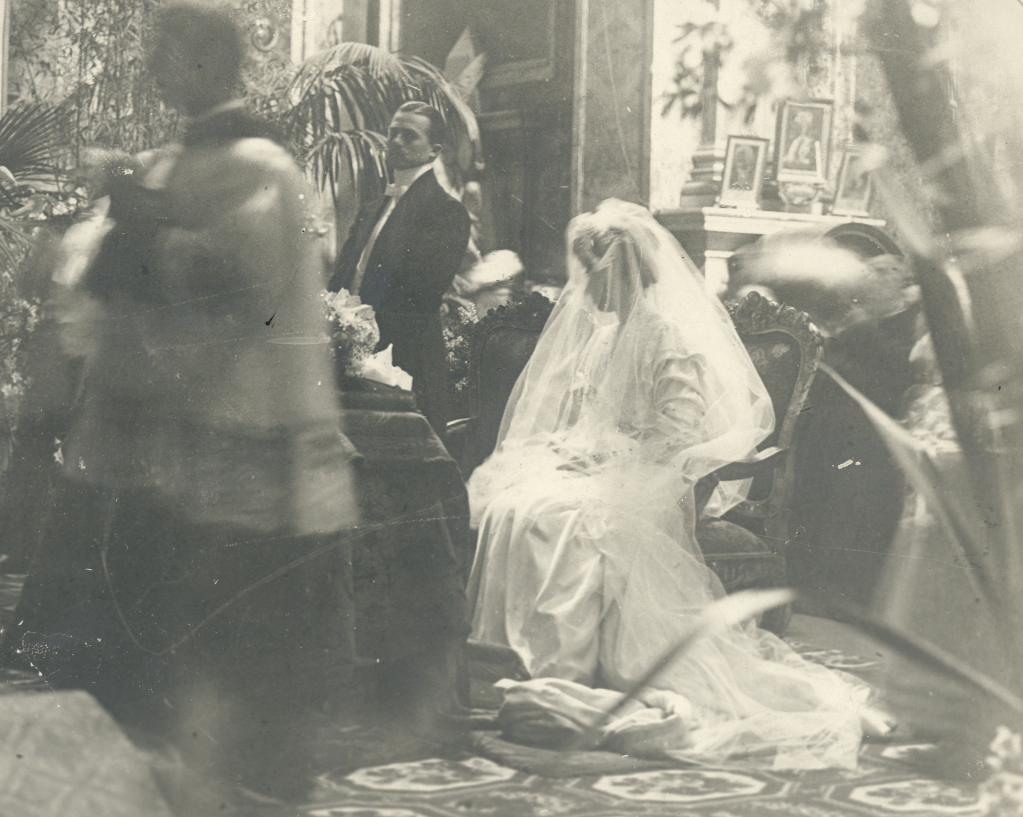

Nicoletta married Prince Francesco Boncompagni Ludovisi (1886-1955, Duke of Sora at the time, and Prince of Piombino after 1911) on 20 February 1908 in the church of S Marcello al Corso, Rome. The occasion was widely commemorated in the national daily newspapers. La Stampa reported their wedding as sumptuous, with police and guards having to hold back the crowd that had lined up at the church entrance.

The wedding of Prince Francesco Boncompagni Ludovisi and Nicoletta Prinetti Castelletti (20 February 1908) in the church of S Marcello al Corso, Rome. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

Together, Nicoletta and Francesco had 4 children: Laura (1908-1975), Gregorio (1910-1988), Giulia (1914-1996), and Alberico (1918-2005). Nicoletta was especially close with her eldest daughter Laura, who shared her utmost confidence.

Francesco and Nicoletta’s marriage was a steadfast one, if not trying at times. In a 1946 journal entry (found today in the Casino dell’Aurora archive), Francesco describes her as “an exemplary wife and mother, educated, intelligent, beautiful,” someone who had “always been motivated by the constant goal of spiritually and materially elevating her family.” However, he adds: “she had, however, a difficult character, which sometimes made life not easy for those around her, also made her suffer—and she was of an almost scary lavishness.”

In 1928, Nicoletta became First Lady of Rome after Francesco was appointed Governor under Mussolini’s regime. Due to the nature of her position, she played a unique supplemental role to her husband, often hosting events at their main residence, the Casino dell’Aurora in Rome, and making numerous public appearances.

Excerpt from New York Times article (3 March 1929) by Arnaldo Cortesi on Princess Nicoletta Boncompagni Ludovisi and her followers. Credit: New York Times

Cortesi’s article on Nicoletta was published on the first Sunday of March 1929. It discusses Nicoletta as the leader of a group of Roman socialites who sought the development of a national fashion industry. According to Cortesi, these women vowed only to wear clothing that had been designed and manufactured by Italians, and that had been made solely using Italian materials.

Cortesi places this movement in opposition to the current styles, contrasting it especially with French clothing, which was considered very tasteful at the time. He does not include any concrete descriptions of the sorts of styles Nicoletta and her followers were wearing, but he suggests that they intended to reconcile their campaign with the Church, implying a shift towards a more modest mode of fashion, with longer skirts and sleeves, and higher necklines. This would put her movement in contrast with 1920s fashion as a whole, with its knee-length hemlines and more revealing nature (as compared to styles from previous decades).

Arnaldo Cortesi (1897-1966) in 1938. He served as the foreign correspondent for Rome from 1922-1939, writing on Mussolini’s rise and accurately predicting his future alliance with Hitler. He received a Pulitzer Prize for journalism in 1946. Credit: The Old Shirburnian Society

The timing of the release of this article is very interesting considering the signing of the Lateran Accords not quite a month earlier, on 11 February 1929. (It was Francesco Boncompagni Ludovisi who first publicly announced the agreement.) Indeed, Cortesi references the treaty in his article, using Nicoletta’s crusade as a launching point into his discussion of it.

On a conceptual level, Nicoletta’s movement fits neatly into the broader alliance between the Church and Mussolini that had been established by the Accord. Its emphasis on modesty displays a clear religious and political bent, in line with both the ideals of the Church and Mussolini’s own value on tradition. During the late 1920s, Mussolini began presenting himself in an overly historicized way; this proposed reversion to longer hemlines and higher necklines very much could have been a part of that trend. Overall, considering the prominence of her political position (as well as Francesco’s), Nicoletta’s movement could have been a way to cement this alliance on a cultural level, as a show of Italy’s goodwill toward the Catholic Church and Vatican City.

Whether or not Nicoletta’s efforts gained much traction outside her inner circle is unclear, and indeed seems unlikely. Mentions of Nicoletta are few and far between in all media. She does not seem to have appeared in contemporary newsreels. Newspapers, prominent Fascist periodicals, and women’s magazines of the era mostly relegate Nicoletta to descriptions within society pages of events she hosted and attended. There is also no coverage of Nicoletta in relation to fashion in the Boncompagni Ludovisi family’s extensive personal photo collections and albums in the Casino dell’Aurora.

Other parts of the archive might hold answers to some of these questions—particularly as to her relationship with Cortesi and specific details of the fashion of the movement. However, they are not currently accessible, and these questions may remain unanswered, at least some time. It is quite possible that Cortesi’s article, quite vague in its details, does not represent reporting of a genuine phenomenon, but rather was a “plant”—one that failed to take root.

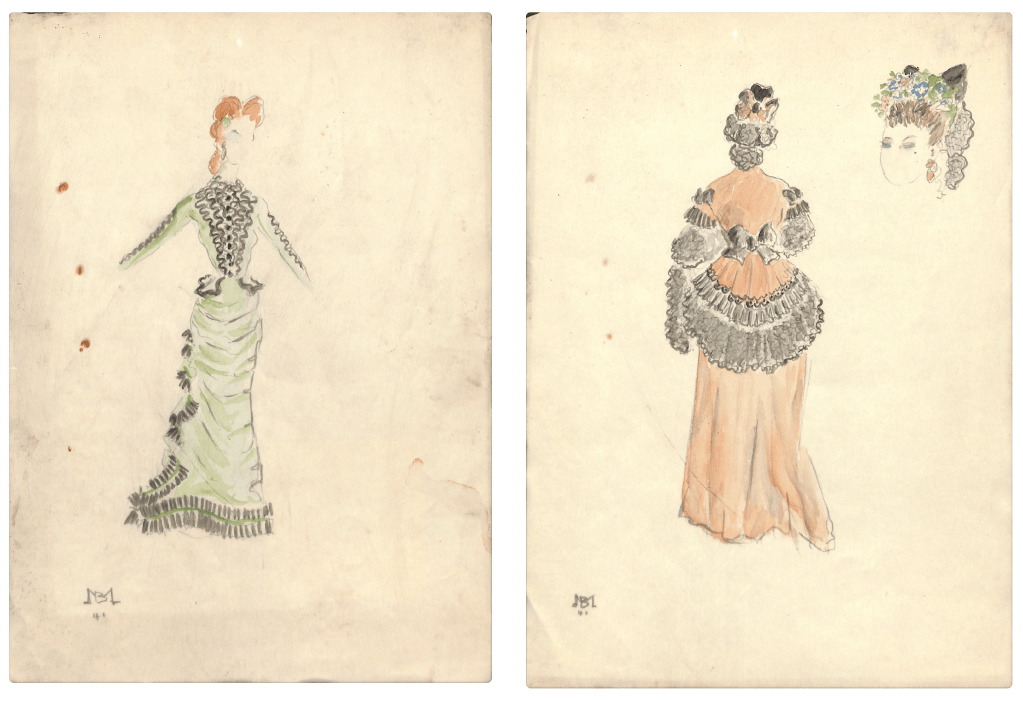

Dress sketches inscribed with Princess Nicoletta Boncompagni Ludovisi’s signature “NBL.” Likely drawn after her 1908 wedding. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

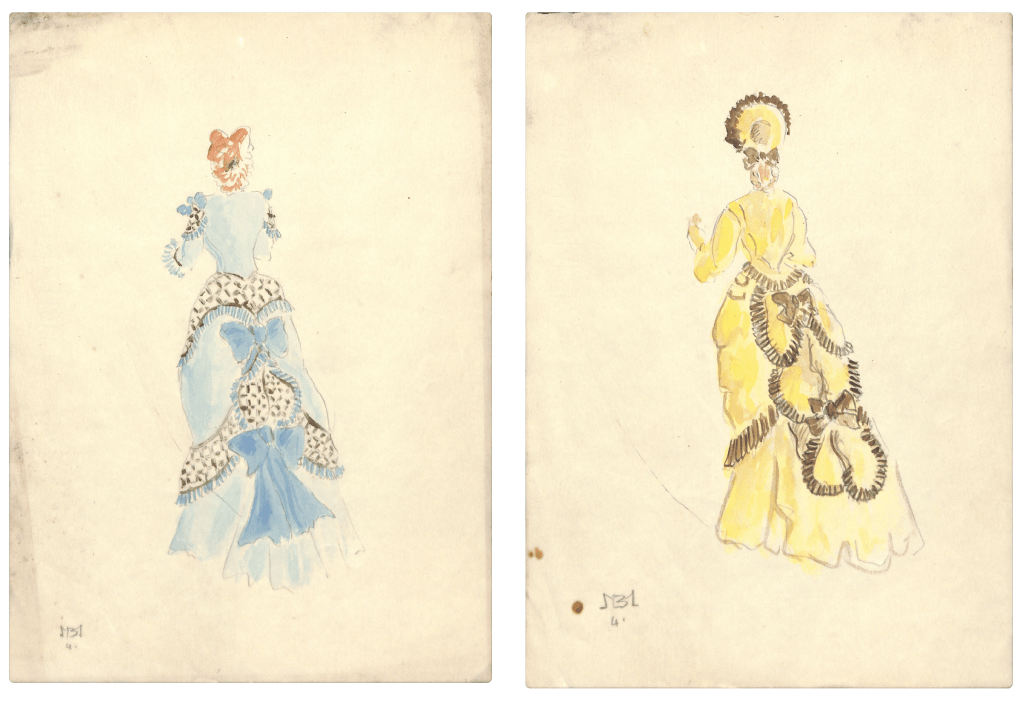

Fortunately, there are some documents that might hint at Nicoletta’s own relationship with design. Easily missed within the extensive archive in the Casino dell’Aurora are a few dress sketches, devised in patterns resembling those of the late Victorian age (specifically, the early 1880s). The exact date these sketches were created is unknown. But as they are signed “NBL,” Nicoletta must have drawn them sometime after her 1908 wedding. Considering the discrepancy between the point after which the sketches must have been made and the dated style of the design, this could point to Nicoletta having a more nostalgic view of fashion on a personal level as well.

Dress sketches inscribed with Princess Nicoletta Boncompagni Ludovisi’s signature “NBL.” Evidently drawn after her 1908 wedding. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

After suffering sudden intestinal paralysis, Nicoletta died on 2 March 1931, aged only 39. Francesco in the same journal entry describes the cause of her death as a strangulated hernia, blaming Nicoletta’s surgeons for operating on her too late. In obituaries memorializing her, Nicoletta is remembered as intelligent, kind, and generous. She is particularly noted for her charitable works, such as those regarding tuberculosis prevention and women’s work.

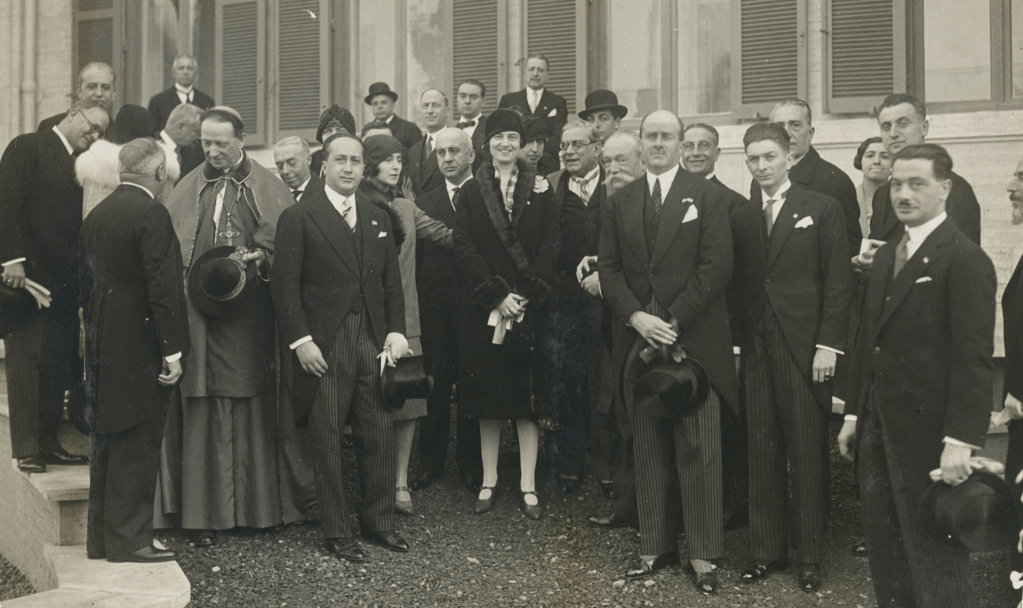

Princess Nicoletta Boncompagni Ludovisi (center, flanked by Filippo Pannavaria and, with crossed hands, her husband Francesco Boncompagni Ludovisi) participating in the inauguration of Rome’s Istituto Materno ‘Regina Elena’ on 18 November 1928. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

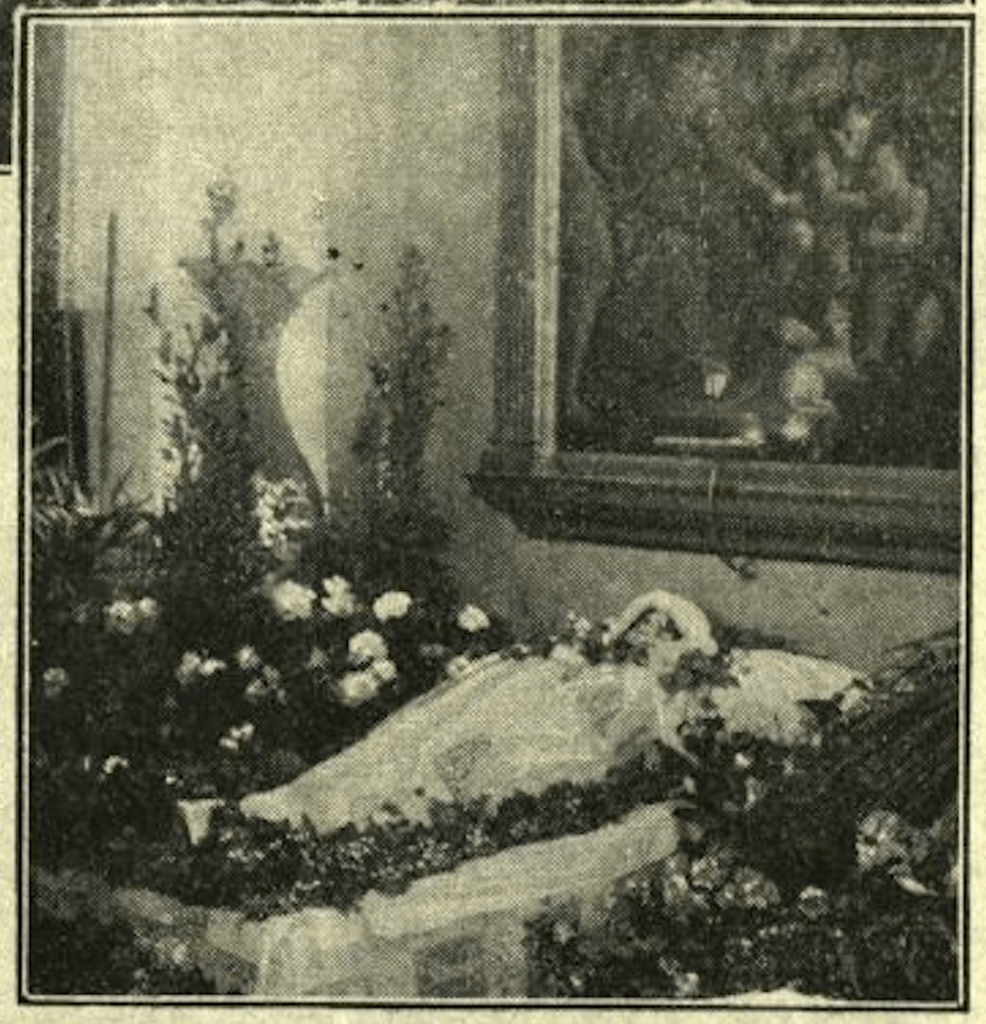

On 3 March 1931—a Tuesday—Nicoletta was laid in state on the piano nobile of the Casino dell’Aurora, in the ornate room frescoed by Pietro Gagliardi that depicted scenes from the life of Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni. In a photo of this grim scene, visible behind Nicoletta is a painting by the 16th century Lombard painter Bernardino Lanino (1512-1583) of the Holy Family with S Anna, S John the Baptist, and other Saints, that she had brought to Rome at the time of her marriage as part of her own art collection. Its present location is unknown. (Thanks for the identification is owed to prof.ssa Patrizia Zambrano, Università degli Studi del Piemonte Orientale.)

Above: image of the wake of the Princess of Piombino, held in a grand Sala on the Piano Nobile of the Casino dell’Aurora. Credit: La Tribuna Illustrata (15 March 1931). Below: a prized item in Nicoletta Boncompagni Ludovisi’s large collection of art was Bernardo Lanino (1512-1583), Sacra Famiglia con sant’Anna, san Giovannino e santi. It a 1946 family inventory it was counted as one of the most valuable easel paintings then in the Casino dell’Aurora. Credit: Fondazione Federico Zeri

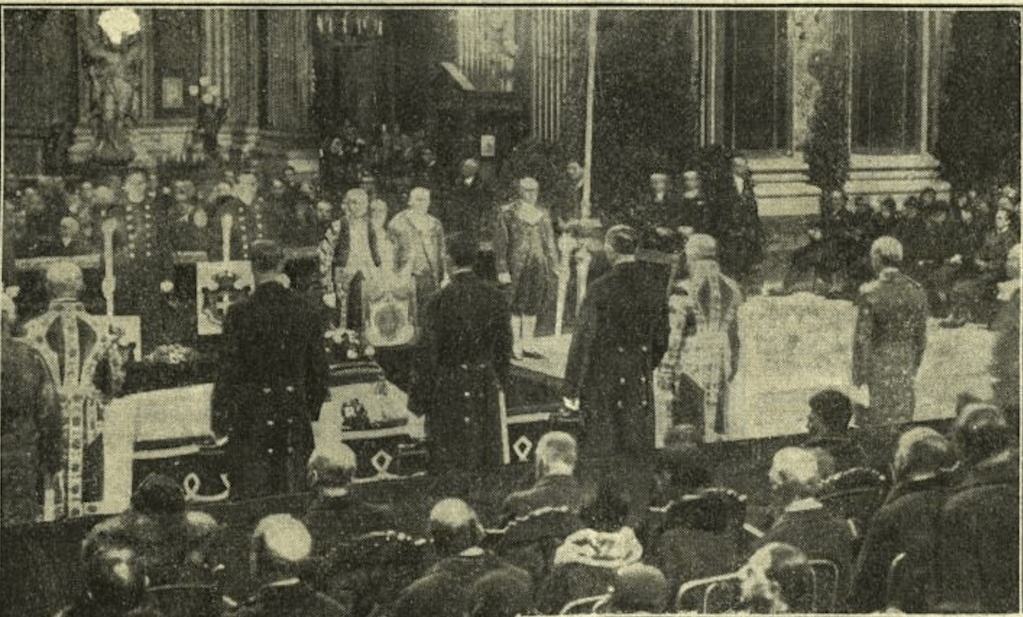

Nicoletta’s funeral was held the next day, on the morning of 4 March 1931, in the Boncompagni Ludovisi family church of S Ignazio in Rome. As La Stampa reports, numerous public officials and members of the aristocracy were in attendance. Mussolini himself paid his respects at the service, expressing his condolences to Francesco, and to Nicoletta’s children. King Vittorio Emanuele III and Queen Elena also paid tribute to her in the form of floral arrangements, as did the Queen Mother. Nicoletta was buried in the Boncompagni Ludovisi family mausoleum at Rome’s Verano Cemetery.

Above: Princess Nicoletta Boncompagni Ludovisi’s funeral procession leaves the Casino dell’Aurora (4 March 1931). Images of the huge crowds accompanying her casket are numerous. Credit: Archivio LUCE (colorized by TC Brennan). Below: Princess Nicoletta ’s funeral (4 March 1931) in Rome’s S Ignazio, attended by Mussolini himself. Credit: La Tribuna Illustrata (15 March 1931).

In a tribute to the recently deceased Princess of Piombino, Maria Magri Zopegni, the editor of the women’s magazine La Donna Italiana, names Nicoletta as the honorary president of the Laboratory for the Unemployed charity organization. Intriguingly, she notes that Nicoletta helped secure the financial means from Italy’s Queen Elena to purchase sewing machines and help young women regain employment to support their families. Zopegni further remarks that through her deeds, Nicoletta earned the moniker of “The Good Princess” from the workers she helped.

Journalist Maria Magri Zopegni’s tribute to Princess Nicoletta Boncompagni Ludovisi in the women’s magazine La Donna Italiana (March 1931). Credit: Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma

Isha Gullapalli is a rising junior in Rutgers-New Brunswick’s School of Arts & Sciences, majoring in Psychology and Classics. This spring she was inducted into two academic honors societies, Psi Chi (for Psychology) and Eta Sigma Phi (for Classics). In the 2024-2025 academic year Isha interned with the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi under the auspices of Rutgers’ Aresty Undergraduate Research Program. Isha adds “I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Professor T. Corey Brennan for his guidance and for granting me the opportunity to work with such an invaluable collection of primary source material, and to HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for her generosity in making the archive available for study. I’m honored to have been able to work on this project.“

Spring 1925: Nicoletta Boncompagni Ludovisi (born Prinetti Castelletti) and her daughter Laura, newly engaged. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

Leave a comment