By Lydia Francoeur (Rutgers ’21 and ’27)

Even Rome’s most noble families had their financial limitations. Throughout the early modern period, indeed, into the twentieth century, many chose to place their daughters in convents to avoid paying the requisite dowry.

The Boncompagni Ludovisi family was no different. The patriarchal nature of Roman nobility forced the family to invest in the success of their male heirs to continue their dynasty. As a result, the stories of many Boncompagni Ludovisi women have escaped our attention.

The Boncompagni Ludovisi Archive in the Casino dell’Aurora contains a vital amendment to the record: a family biography, in manuscript, of the Boncompagni and (after merger with the Ludovisi in 1681) Boncompagni Ludovisi, both men and women, that starts with the son of Pope Gregory XIII, Giacomo Boncompagni (1548-1612), the first Duke of Sora. The author is Carlo Rosa (1718-1800), a member of the religious order of the Somaschi Fathers. Known regularly as ‘Somasca’, he served the Boncompagni Ludovisi as family archivist from ca. 1757 until 1795. Little is known about Somasca, apart from his role on behalf of the family and its archive. Our most informative source is a 20th century Boncompagni Ludovisi archivist, Giuseppe Felici, who frequently cites Somasca’s work and personal letters.

This biography, entitled Genealogical records of the Boncompagni Family with some notes on its origin, and then connected to the Ludovisi Family, up to the generation of D. Luigi Boncompagni, Prince of Piombino, who died on the day of 9 May 1841, is attributed to “Carlo Somasca, who was the librarian of the Casa Boncompagni until 1795”. The header of the first page further explicates Somasca’s focus: “Genealogical series of the Dukes of Sora of the ancient noble Boncompagno family, later grafted with that of the Ludovisi, [who] became Princes of Piombino.”

Vellum cover of Genealogical records of the Boncompagni Family with some notes on its origin, and then connected to the Ludovisi Family, up to the generation of D. Luigi Boncompagni, Prince of Piombino, who died on the day of 9 May 1841. Cabinet I. Part I. Number 9. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

The importance of the manuscript for the family archive can be seen from its prominent shelfmark: Cabinet I, Protocol 1, Number 9. Somasca’s genealogical record contains over 170 pages of information about the family, beginning with the family’s Bolognese origins. The manuscript includes biographies of 50 family members from the late 16th through the 18th century, with further entries documenting events in the early 19th century. Most of these individuals were born in the Boncompagni palace at Isola dl Liri in southern Lazio, the family’s main residence in their Duchy of Sora. As Somasca died by 1800, the later entries obviously were completed by a different author. A radical shift in handwriting styles occurs on page 160 of the Genealogical Records, suggesting that pages prior were completed by Somasca while subsequent entries were completed by the unknown author.

One of the most valuable attributes of this compendium of biographies is that it provides brief histories of the most overlooked members of the family, namely the Boncompagni women who entered convents and became nuns in the late 16th and 17th centuries. (Somasca was not concerned with the Ludovisi before the 1681 merger, and no Boncompagni Ludovisi women entered the convent in the 18th century.) For the Boncompagni nuns, a pattern emerges, with a very select number of convents favored: in the 16th century, S Paolo Convertito in Milan; and in the 17th century, S Marta in Rome and S Giuseppe de’ Ruffi in Naples.

As the family archivist, Somasca veered toward eulogy in chronicling the lives of the Boncompagni and Boncompagni Ludovisi who reached adulthood. As a priest, he took a specific interest in the Boncompagni daughters who entered religious life—women who were often overshadowed in the historical record by family members with influential public lives.

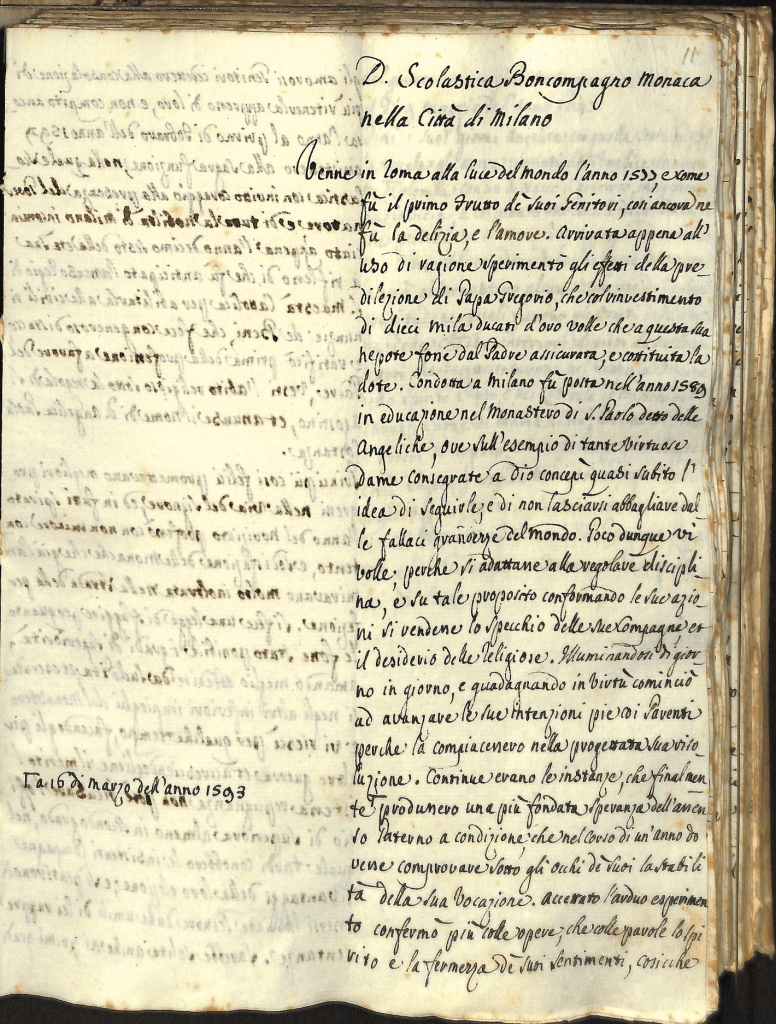

Excerpt from Carlo Rosa alias Somasca, Memorie genealogiche della famiglia Boncompagni (ca. 1795), here the first page of his biography of Scolastica Boncompagni = Sister Maria Angelica Paola Costanza (1577-1647), a granddaughter of Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni (r. 1572-1585). Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

In his entries on the Boncompagni nuns, Somasca provides a brief description of historical statistics on the nuns, including dates of birth, particulars of their education in the convent, the dates they took their habit, the dates on which they renounced their worldly possessions and took their final vows, and their dates of death . A total of twelve Boncompagni nuns are chronicled over the course of his biography, spanning three generations and five convents. Here I provide a summary of Somasca’s entries:

First Generation: Daughters of Giacomo Boncompagni (1548—1612, son of Gregory XIII) and Costanza Sforza (1560—1617), Duke and Duchess of Sora I

- Scolastica Boncompagni (1577—9 May 1647) first entered the convent of S Paolo Convertito in Milan in 1589, for education under the Angeliche order of nuns. She joined them as a novice on 16 March 1593, then professed her formal vows on 1 February 1594 not yet aged 17. She took as her religious name Maria Angelica Paola Costanza. At that time, she renounced her worldly possessions in favor of her father, Giacomo (I) Boncompagni. Somasca notes “had she lived longer, she likely would have attained the highest ranks of governance”, though she died at age 69 or 70.

- Veronica Boncompagni (1584—23 November 1609) joined her elder sister Scolastica as a student at the Convent of S Paolo Convertito in 1591. She took her habit as a novice there on 25 April 1600, followed by perpetual vows on 10 April 1601 at the age of 17, adopting the name Angelica Scolastica Maria. She too renounced her worldly possessions in favor of her father, Giacomo Boncompagni.

- Cammilla Boncompagni (1591—15 January 1631) at age 12 “was left in Rome in the monastery of S Cecilia of the Benedictine Order”, in April 1603. The community was cloistered. Somasca explicitly tells us that Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrati (1560-1590-1618, nephew of Gregory XIV)—who in 1599 had rediscovered the incorrupt body of the third century martyr S Cecilia in her namesake church—facilitated Cammilla’s unusually rapid integration into the Benedictines. Aged no more than 15, Cammilla received her habit in the church’s Convent on 16 December 1606, and just four days later professed her vows, taking the name Maria Cecilia. Somasca does not indicate in whose favor Cammilla renounced her property, but one assumes her father Giacomo (I), who was still alive.

Second Generation: Daughters of Gregorio (I) Boncompagni (1590—1628) and Leanor Zapata y Brancia (1593 – 1679), Duke and Duchess of Sora II

- Caterina Boncompagni (23 February 1619—29 October 1699), relates Somasca, “was placed in the boarding school within the Monastery of S Cecilia in Rome, entrusted to her aunt [Cammilla Boncompagni] who resided there as a professed Benedictine nun”. When Caterina’s aunt died in January 1631, she returned home around for about three years. On the encouragement of her mother, Caterina at age 15 entered the Convent of S Marta in Rome as an Augustinian novice (2 June 1634). She took her final vows on 10 June 1635 at the age of 16. She chose Maria Eleonora as her name. She renounced her worldly possessions in favor of her brother, Giacomo (II) Boncompagni (1613–1636, Duke of Sora III), who died in Naples just 10 months later. She served a total of 12 years as the Superior of the S Marta convent; she also personally funded the construction of a high altar for the S Marta church, dedicated in 1696. “Even Queen Christina of Sweden [1626-1689, abdicated 1654] honored her more than once with personal visits” says Somasca.

- Maria Boncompagni (1620—11 December 1648) entered the Convent of S Marta in Rome as a novice 8 May 1639, taking the name Maria Pulcheria. She took her vows in 1640, at the age of 20. She renounced her worldly possessions in favor of her brother, Ugo Boncompagni (1614—1676), who after the untimely death of his elder brother Giacomo (II) in 1636, had found himself as head of the Boncompagni family. Maria Pulcheria herself died aged just 27 or 28.

- Cecilia Boncompagni (12 March 1624—25 September 1706), was the third Boncompagni sister to enter the Convent of S Marta in Rome as a novice, on 25 March 1642, shortly after her 18th birthday, taking the name Maria Grazia. She took her vows on 10 May 1643, at the age of 19, eight days after having renounced her property in favor of her brother Ugo. “When Sister Maria Eleonora [= her older sister Caterina Boncompagni] died in 1699”, relates Somasca, “Sister Maria Grazia was elected to succeed her as abbess with full approval of all the professed sisters.” In his biography, Somasca mentions that in 1705 she witnessed two of her nieces transfer from the S Marta convent to another Augustinian community, that of S Lucia in Selci on Rome’s Esquiline hill, and notes the date of her death the next year.

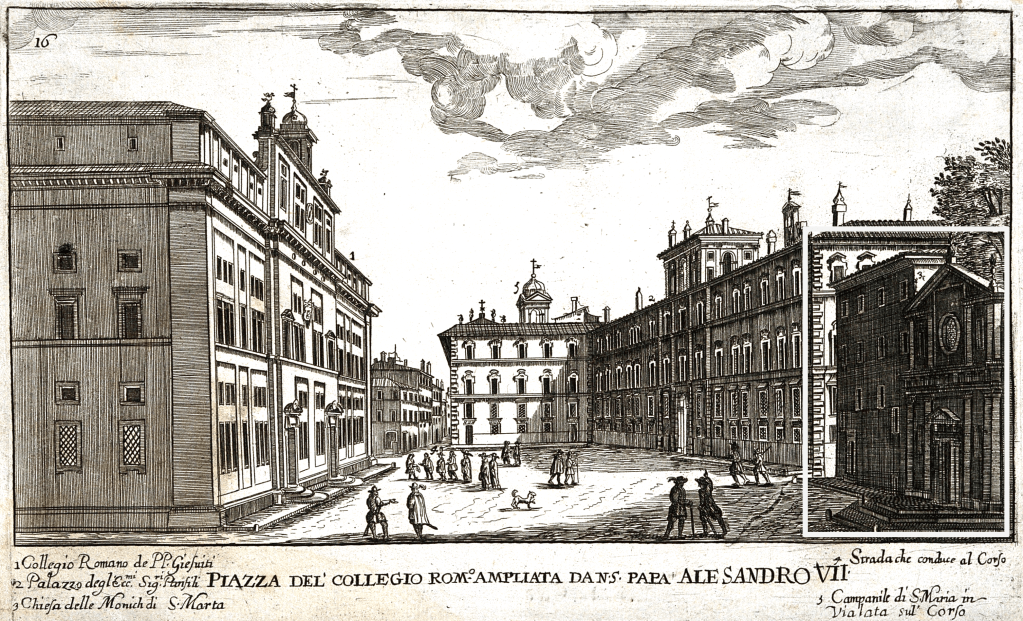

“Piazza of Collegio Romano, extended by Pope Alexander VII [r. 1655-1667]”, with convent and church of S Marta at right (in rectangle), by Giovanni Battista Falda (1665). Credit: Wellcome Collection

Third Generation: Daughters of Ugo Boncompagni (1614—1676) and Maria Ruffo di Bagnara (1620—1705), Duke and Duchess of Sora IV

- Jumara Boncompagni (11 August 1644—20 February 1716) is introduced by Somasca with her twin sister Costanza in a joint biography. Their mother Maria Ruffo, Somasca tells us, brought the two—then aged 10 or 11—to Naples in 1655, where she “managed, not without effort, to place them both as boarders in the Monastery of Saint Giuseppe, founded at the family’s expense by one of their ancestors as a retreat for those ladies of the family who especially desired to consecrate themselves to the Lord under the rule of S Augustine”. They both formally entered the convent of S Giuseppe de’ Ruffi as novices in 1662, Jumara taking the name Maria Girolama. She and her twin sister professed their final vows on 31 July 1663 at the age of 19. Jumara (like Costanza) renounced her property in favor of her father Ugo. Somasca emphasizes her talent and energy. He relates of Jumara that “three times she was elected prioress by unanimous vote”; and in 1710, Cardinal Giacomo Boncompagni [1652-1695-1731], Archbishop of Bologna and her brother, had entrusted her with the oversight of three abbeys he held in the Kingdom of Naples”.

- Constanza Boncompagni (11 August 1644—1718), like her twin sister Jumara, entered the convent of S Giuseppe de’ Ruffi in Naples as a novice in 1662, taking as her name Maria Cecilia. The two took their final vows together on 31 July 1663, renouncing their property in favor of their father. After recording this act, Somasca in his joint biography of the twin sisters focuses largely on Jumara except to note that Costanza outlived her sister by two years, dying in 1720. Within their joint biography, Somasca highlights their sisterly bond and the grief Constanza endured following the death of her sister.

- Giulia Boncompagni (30 July 1647—17 August 1715) “was placed in education in the Monastery of S Marta in Rome under the care of two aunts”, i.e., the former Caterina and Cecilia Boncompagni, as Somasca reports. She herself entered the convent of S Marta as a novice in February 1666, taking the name Angelica Eleonora, with final vows on 6 February 1667. She renounced her worldly possessions in favor of her father Ugo. Somasca notes that “in the year 1679, when Duchess [Leonor] Zappata passed away, there were, in addition to the two daughters of this Lady, three professed Boncompagni nuns who were her granddaughters—each daughters of Duke Ugo and Duchess Maria Ruffo—who were all present for the suffrages at the transport of the Duchess’s body and its burial in their church”. The three granddaughters who witnessed Leonor Zapata’s burial in the church of S Marta were Giulia and her younger sisters Giovanna and Anna, on whom see below. In 1705, Sister Angelica Eleonora was transferred from S Marta to the convent of S Lucia in Selci.

- Giovanna Boncompagni (22 May 1649—30 October 1688) with her younger sister Anna was “invited to Rome by her aunts and sister who were already nuns in the Monastery of S Marta”, says Somasca, and “she was placed there for her education”. In coordination with her younger sister, Giovanna entered the convent of S Marta in Rome as a novice on 11 June 1668, taking the name Maria Maddalena Felice. She took her final vows on 4 July 1669, on 12 July renouncing her inheritance in favor of her father Ugo. Somasca notes Giovanna’s delicate health, and that after a grave illness she died “at eleven-thirty in the evening on the 30th of October” 1688, aged 39.

- Anna Boncompagni (25 February 1651—12 April 1707) was sent to S Marta at the same time as her elder sister Giovanna “so that she might be educated”, explains Somasca, “under the guidance of the Boncompagno nuns”, already three in number at that convent. Giovanna and Anna both entered the convent of S Marta as novices on 11 June 1668 (the latter adopting the religious name Anna Vittoria), and together took final vows on 4 July 1669. She too renounced her worldly possessions in favor of her father Ugo. In 1705, she was transferred from the S. Marta to S Lucia in Selci, where she died two years later “afflicted in her chest by a pernicious cancer”.

- Antonia Boncompagni (21 September 1654—20 March 1714) “entered the Monastery of S Giuseppe de’ Ruffi in Naples as a boarding student, where, in the year 1663, two of her sisters [i.e., the twins Jumara and Costanza] had professed that Regular Institute. Exactly ten years later, in the year 1673, she too resolved to make her profession, taking the name Sister Maria Angelica.” She took her final vows on 13 February 1674 at the age of 19, renouncing her inheritance in favor of her father Ugo. Somasca finds it noteworthy that “although she was younger in age than her two nun sisters, she died on 10 March 1714…[and] that in two consecutive two-year periods (i.e., 1716 and 1718), her sisters also passed away”.

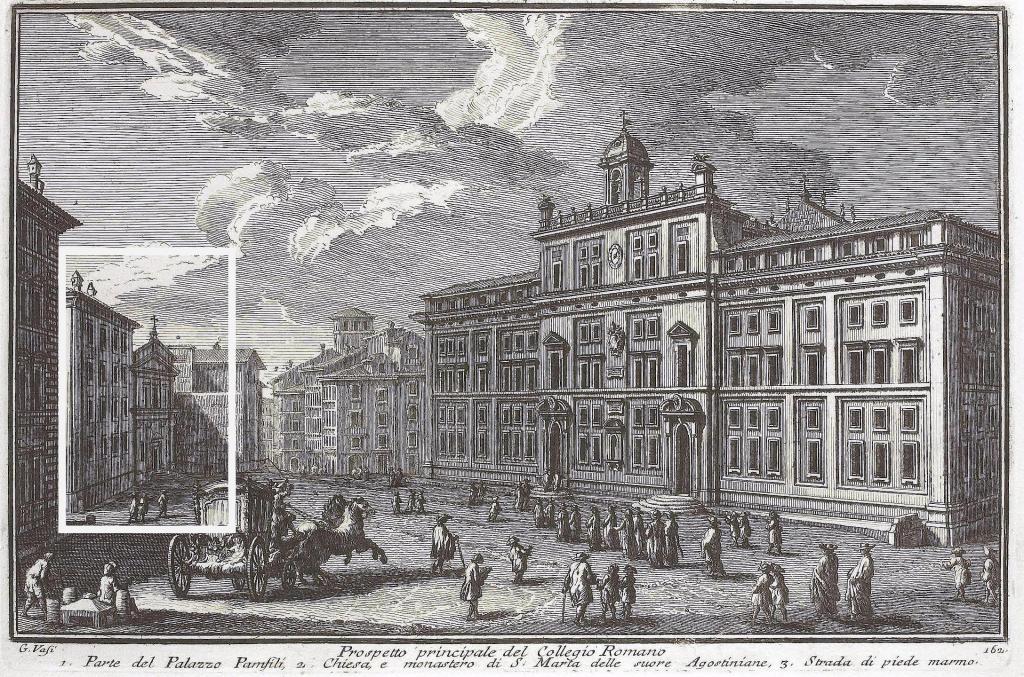

Though obviously well informed on the details of these Boncompagni nuns—in one case even noting the hour of death—Somasca does not share much about the S Marta convent in Rome where five women of the family took vocations in the 17th century. The convent’s location is a prime one, in the Pigna district in the very center of the historic city, on the south side of a piazza opposite the Collegio Romano, the monumental school built by Jesuits in 1584 under the patronage of Gregory XIII Boncompagni. It is also lies just west of the Palazzo Doria Pamphili.

‘Prospetto principale del Collegio Romano’ by Giuseppe Vasi (1786), view of the Collegio Romano from the Palazzo Panfilio, today known as the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj. In the upper left corner (in rectangle) is the S Marta Monastery, adjacent to the church of S Marta. Credit: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg

Before it was a convent, the building was known as the Casa di S Marta. Founded by Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556) in 1543, it served to rehabilitate malmaritate—unhappily married women who were likely facing domestic violence or at risk of entering prostitution. Ignatius named the house for Saint Martha, revered as the patroness of housewives, cooks, and more generally hospitality for hosting Jesus in her home during his travels in Judaea. Shortly after Ignatius’ death in 1556, the malmaritate women were transferred to the Monastery of the Magdalene in Rome, and the building was entrusted to Augustinian nuns, thereby officially establishing the S Marta convent.

Pierre Hélyot (né Hippolyte Hélyot, 1660-1716) briefly details the convent in his book L’Histoire des ordres monastiques, religieux et militaires, et des congregations séculières de l’un et de l’autre sexe, qui ont été établis jusqu’à présent, published in eight volumes between 1714 and 1719. Hélyot—a contemporary of the second and third generations of Boncompagni nuns—explains that entry into this convent was reserved for princesses and noblewomen of the highest rank. This effectively transformed the convent from a convertite institution for underprivileged women into an elite enclave.

As an Augustinian convent, the nuns of S Marta followed the Rule of Saint Augustine, living in communal monastic unity, isolated from greater society. Heylot emphasizes the architecture and geographic location of S Marta enabled the nuns to maintain their isolation, as the convent was enclosed by four major streets.

“Augustinian Nun from the S Marta Monastery in Rome in Winter Habit”, in Pierre Hélyot (né Hippolyte Hélyot), L’Histoire des ordres monastiques III (1715) plate facing p. 54. Credit: BnF Gallica

In addition to providing insight on the situation and social composition of the S Marta convent, Pierre Hélyot in his L’Histoire des ordres monastiques (1714-1719) provides critical information on the nuns’ habits. According to the Augustinian Rule, nuns are not bound to wear a certain color habit or uniform. As a result, the style and colors worn differed in each convent. The S Marta nuns wore white habits with a black scapular over their shoulders. During the winter months, they wore a black robe over their white habit.

Although modest compared to the biographies of other family members, Somasca provides more general reflections about the Boncompagni nuns of S Marta. Most notably, Somasca details the financial and political power of Sister Maria Eleonora (née Caterina Boncompagni) who served as S Marta’s Abbess for 12 years. Somasca mistakenly thinks she was “elected for two consecutive six year terms”; the convent’s own financial records, now in the Vatican Apostolic Archive, show rather that it was 1670-1676 and 1685-1691. While Abbess, Sister Maria Eleonora helped fund renovations to the Church of S Marta from her personal resources. To restore the Church and enlarge the monastery, Sister Maria Eleonora commissioned in 1688 the noted architects Giovanni Antonio de’ Rossi (1616–1695) and Carlo Fontana (1638-1714), the latter being primarily responsible for the church’s marked Baroque style. (On this and what follows, see especially M.R. Dunn, “Nuns as Art Patrons: The Decoration of S. Marta al Collegio Romano“, The Art Bulletin 70 (1988) 451-477.)

In 1671 or 1672, Sister Maria Eleonora had commissioned the artist Guglielmo Cortese (1628-1679, known as ‘ Il Borgognone’) to paint a Christ in the House of Mary and Martha, to be placed on the highest altar. This painting is believed to be Cortese’s last work.

Left: Christ in the House of Mary and Martha by Guglielmo Cortese, ca. 1671 – 1672. Right: original frame for Cortese’s painting commissioned by Sister Maria Eleonora. The work was moved to SS Quattro Coronati in Rome after S Marta was acquired by the Italian State in 1773 and deconsecrated. Images: D. Graf, Master Drawings 10 (1972) 357.

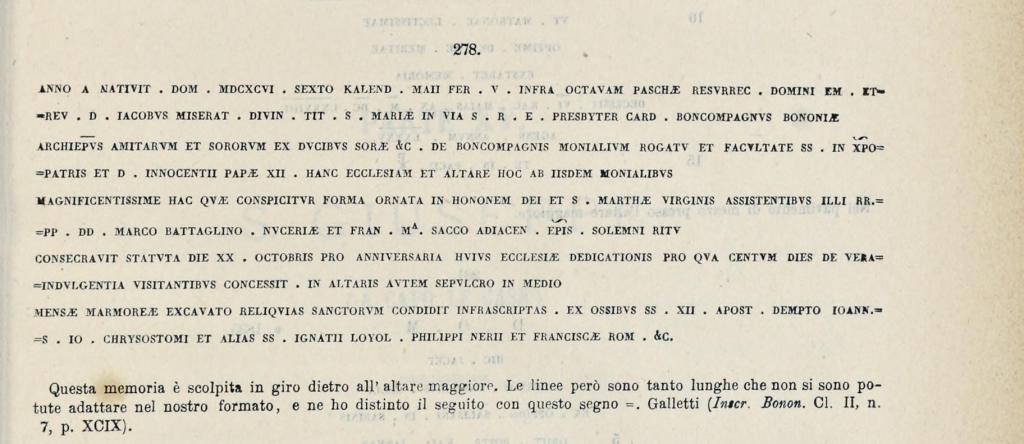

Sister Maria Eleonora’s contributions to the S Marta church later came to the attention of librarian and historian Vincenzo Forcella (1837-1906), who in a magnum opus catalogued epigraphic inscriptions throughout Rome (Inscriptions of the Churches and Other Buildings of Rome From the 11th Century to Our Present Day, published 1869-1884). Forcella records the following long inscription, carved in a circular fashion behind the highest altar of the church, that honored Sister Maria Eleonora’s renovations. The inscription details how her nephew Giacomo Boncompagni (1652-1731) solemnized the church and its altar shortly after being elevated to the Cardinalate on 12 December 1695:

“In the year of our Lord 1696, on the sixth day before the Kalends of May [i.e., 26 April], a Thursday, within the Octave of Easter, the Most Eminent and Reverend Lord Iacobus Boncompagni, by divine mercy titular Cardinal Priest of S Maria in Via [in Rome], Archbishop of Bologna, at the request of his aunts and sisters, and with the authority of Our Most Holy Father in Christ, and of Pope Innocent XII, consecrated this church and this altar, which the nuns most magnificently adorned in the form that is now visible, to the honor of God and of Saint Martha the Virgin.”

The inscription goes on to note that the Boncompagni cardinal granted “one hundred days of true indulgence to those who visited” on the 20th of October, which henceforth was to mark the anniversary of this church’s dedication. Furthermore, in the altar Cardinal Boncompagni is said to have deposited as relics bones of the Twelve Apostles (“excluding John)”, of SS John Chrysostom, Ignatius of Loyola, Philip Neri, and Francesca Romana, among others.

Transcribed Inscription from S Marta Church in Vincenzo Forcella’s Iscrizioni delle chiese e d’altri edificii di Roma dal secolo XI fino ai giorni nostri X (1877) p. 171 no. 278

Somasca confirms Sister Maria Eleonora’s substantial financial contribution to S Marta—noting that she funded the high altar “entirely herself”—as well as the role of her nephew, Cardinal Giacomo Boncompagni, in consecrating the improvements to the S Marta church on behalf of the Boncompagni nuns. Indeed, he transcribes the entire dedicatory inscription from 1696. What is unexpected is Somasca’s reference to her relationship counseling Christina, the abdicated Queen of Sweden, who lived in exile in Rome for much of the period 1655 until her death in 1689.

Upon the death of Sister Maria Eleonora on 29 October 1699, Somasca tells us that Sister Maria Grazia (née Cecilia Boncompagni) replaced her sister as Abbess of S Marta. This is another error on the biographer’s part: the convent’s records show that Maria Grazia held this position in 1676-1679 and 1694-1700, and so was Abbess at the time of the completion of the S Marta renovation projects, and in the year of her sister’s death (on the dates, see Dunn, “Nuns as Art Patrons”, pp. 452 and 477). Though soon replaced at Abbess, Maria Grazia still resided at the convent at the time of a most unusual transfer of four nuns—including two of her nieces—who switched to another religious community in 1705.

In the biographies of the sisters Giulia Boncompagni (b. 1647, = Angela Eleonora) and Anna Boncompagni (b. 1651, = Anna Vittoria), Somasca details the story of how in 1705 these two Boncompagni nuns moved from S Marta in Rome to another Augustinian convent, S Lucia in Selci on the Esquiline hill in Rome. The two siblings were followed there by a Sister Maria Pulcheria and a Sister Paola Teresa—not members of the Boncompagni family, but also women from elite families from Sora.

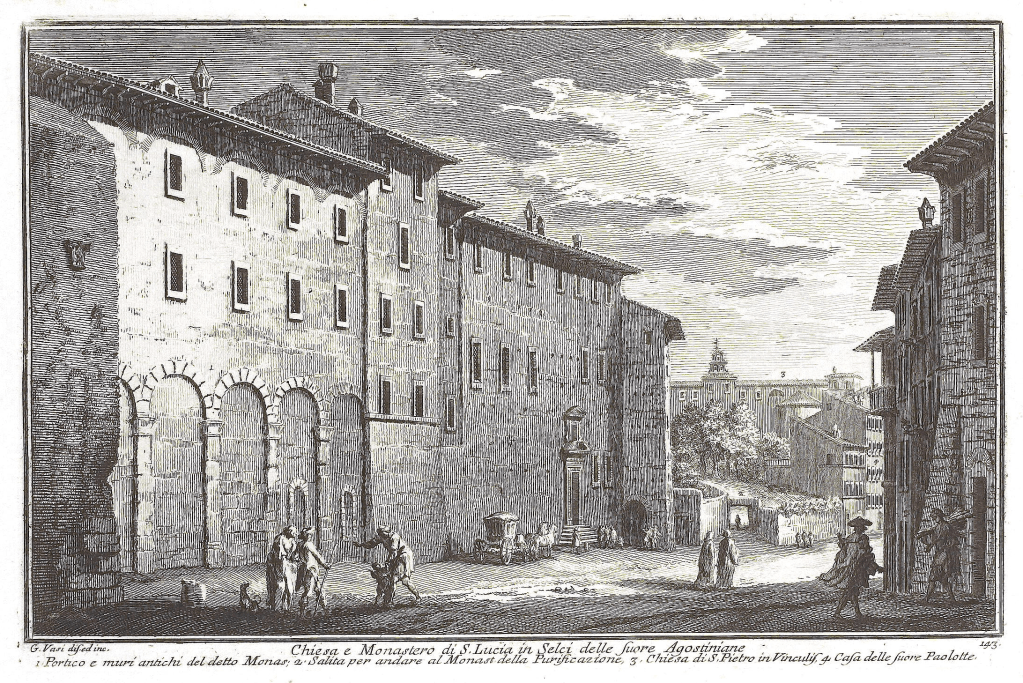

“Church and Monastery of S Lucia in Selci of the Augustinian Sisters” by Giuseppe Vasi (1786). Credit: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg

Somasca alleges that the transfer occurred in pursuit of better health: the nuns suffered from discomforts that remedies failed to cure, and “it was believed their only recourse was to transfer to another monastery in a healthier and more elevated location”. He implies the recent and subsequent deaths of their sibling Sister Maria Maddalena Felice (née Giovanna Boncompagni) in 1688 and their aunt Maria Eleonora (née Caterina Boncompagni) in 1699 greatly affected the welfare of the Boncompagni women. As a result, transferring the nuns to S Lucia was considered the only solution to better the sisters’ health. Somasca reports that Pope Clement XI Albani (r. 1700-1721) granted an apostolic indult permitting the nuns to transfer.

The move took place 19 May 1705. It is worth quoting Somasca on the transfer: “The Protector of S Marta, Cardinal Francesco Barberini [iuniore, 1662-1690-1738], and Sister Angela Vittoria Tedeschi as Abbess, witnessed this change. Monsignor the Vicegerent and Abbot Fatinelli [= Fatinelli de Fatinellis, 1627-1719], assigned to the door of the monastery, delivered the four nuns into the care of the Princess of Piombino, Donna Ippolita Ludovisi (1663-1733), and to the Duchess of Sora, [Ippolita’s daughter] Donna Maria Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi (1686-1745) These noble ladies seated the nuns in a grand coach and having taken their places on the seats by the two doors of the carriage with closed curtains, set off. Upon arriving at the Monastery of Santa Lucia in Selci, in the presence of the named superiors and the entire religious community, the nuns were formally and legally delivered. Sister Maria Grazia, the last remaining Boncompagni nun in Santa Marta, by then eighty years old, did not survive the shock; she died a few months later [on 25 September 1706]”.

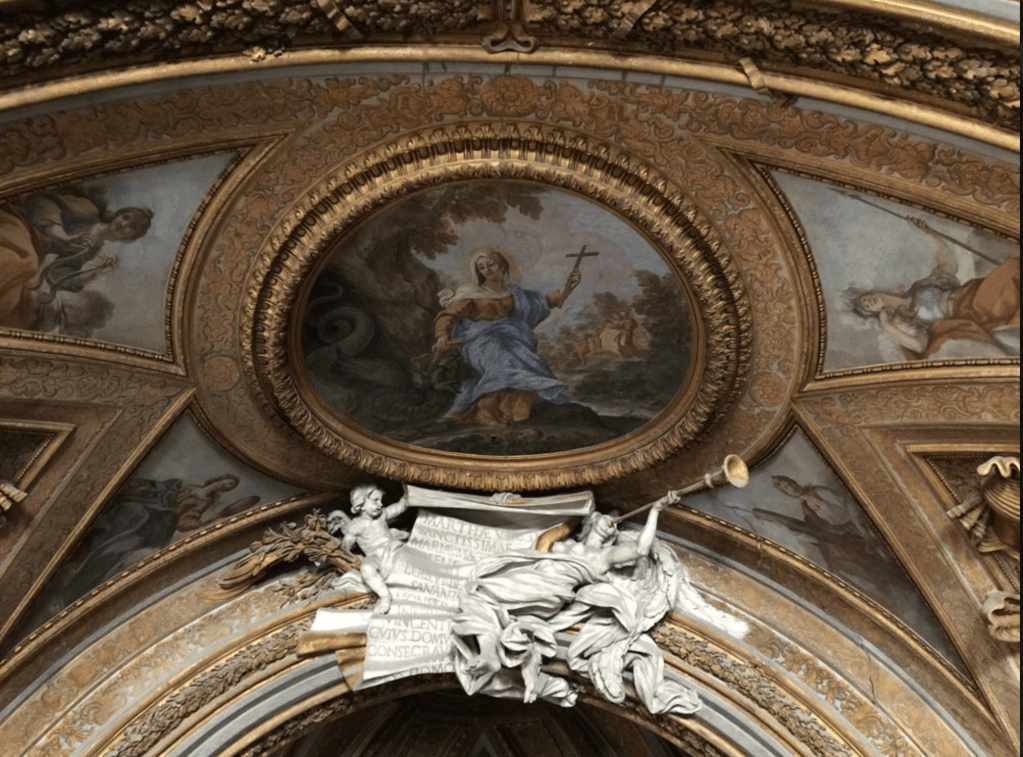

Tondo in ceiling above main altar of S Marta al Collegio Romano: Girolamo Troppa, S Martha Conquering the Dragon (ca. 1673). Credit: tekton.it

Somasca seems to have had a point about the nuns’ health, given the quick demise of Sister Maria Grazia. Of her two nieces who moved to S Lucia in Selci, the younger, Anna Vittoria, was dead in two years (12 April 1707, aged 56); Angelica Eleonora, four years her senior, died eight years later, on 17 August 1715.

Yet Somasca’s account of the 1705 transfer ignores the evidence of over 120 pages of legal documents in the Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi, now housed in the Vatican Apostolic Archive. When Leonor Zapata died in 1679, her will assigned a significant bequest to her daughters Sister Maria Eleonora and Sister Maria Grazia. This included the proceeds from certain flour and silk excise taxes in Zapata’s native Kingdom of Naples. The dispute evidently centered on whether their birth family or the S Marta convent should benefit, given the original renunciations by these two now elderly nuns in 1635 and 1643 respectively. The legal dispute came to a head in 1697-1698, and was fought in both Rome and Naples. A settlement was reached—in the family’s favor—only in 1719 (ABL prot. 623 no. 22; 624 no. 28).

Giuseppe Felici, a 20th century Boncompagni Ludovisi family archivist, in his own extensive (largely unpublished) biographical studies criticized Somasca for being overly panegyric and for providing hagiographic accounts of the Boncompagni family members. The pretext Somasca provides for the 1705 transfer—a quest for better health—conforms to Felici’s criticism of his predecessor’s overly flattering descriptions of the family’s history. However, despite Somasca’s partial narrative of the 1705 transfer, the statistics and facts he presents regarding the nuns remain accurate, despite over-idealizing his biographical subjects and occasionally lacking depth.

No Boncompagni or Boncompagni Ludovisi women are known to have entered religious life after 1674 (Antonia Boncompagni = Sister Maria Angelica, who took vows at S Giuseppe de’ Ruffi in Naples) until the 1880s. Once the Boncompagni and Ludovisi merged in 1681 with the marriage of Gregorio (II) Boncompagni (1642-1707) and Ippolita Ludovisi (1663-1733), the financial limitations that typically nudged the Boncompagni women into religious life presumably were less dominant. It also worth suggesting that the legal lessons learned at S Marta could have discouraged the family from sending its daughters to convents, as it risked claims to inheritance. In addition, Ippolita Ludovisi, reigning Princess of Piombino after being widowed in 1707 and as such the subsequent matriarch of the Boncompagni family, had seven children—a boy who died in infancy, and six girls. She actively advocated for her daughters and ensured that they all had adequate dowries for marriage. None went to a convent. (On Ippolita Ludovisi, and maternal advocacy in general in her era, see Caroline Castiglione, Accounting for Affection: Mothering and Politics in Rome, 1630-1730 [2015].)

Since the era of the 17th century Boncompagni women, the S Marta convent has undergone several major transformations. Under Napoleonic control of Rome, it was deconsecrated. After 1870 and the incorporation of Rome into the Kingdom of Italy, the S Marta convent was converted into a Masonic Lodge. Subsequently, the Italian government seized the convent in ca. 1872-1873 alongside many other convents in Rome. Under ownership of the Italian government, both the convent and the adjoining church were transformed into barracks and a military warehouse. Today, the former convent serves as a police station (Questura) for the Trevi Campo Marzio district, a distant reminder of its historical past.

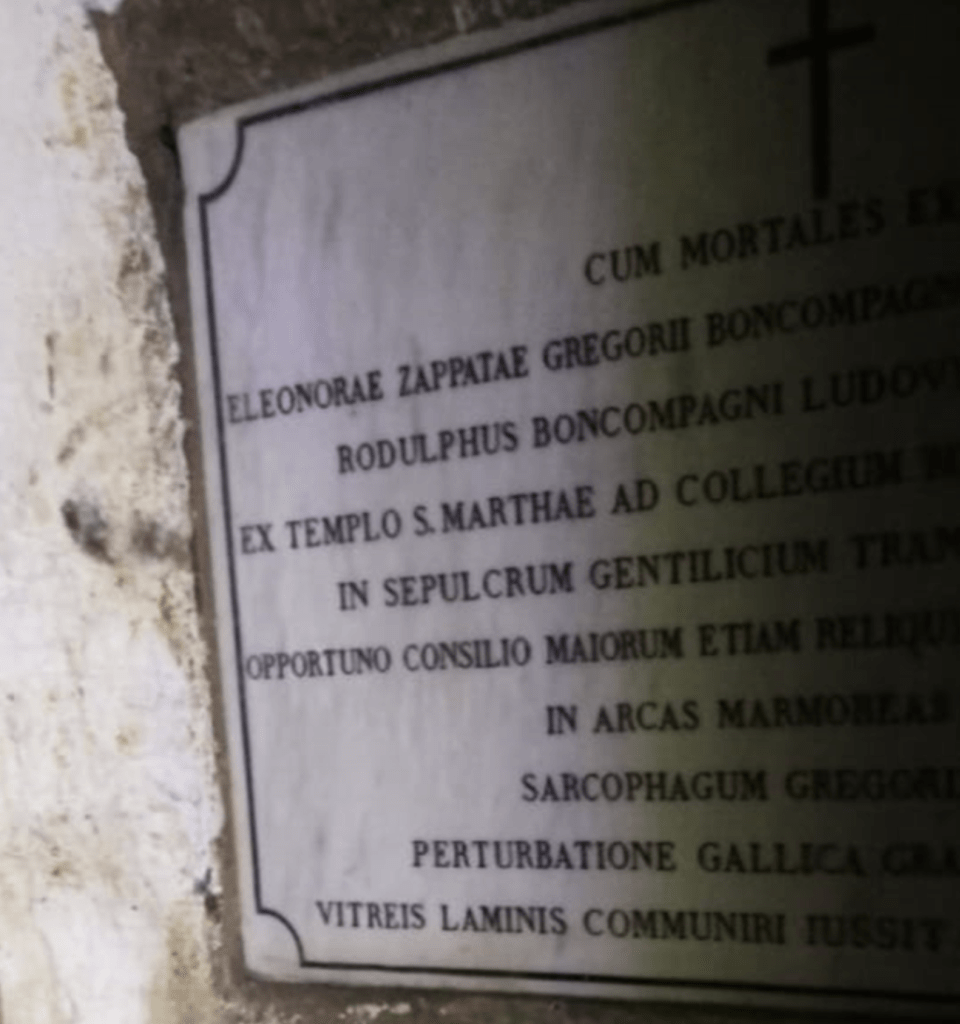

Partial image of Leonora Zapata’s funerary inscription in the Boncompagni Ludovisi family crypt in S Ignazio, taken in extreme conditions in 2018. The inscription implies that her tomb was plundered during the Napoleonic occupation of Rome (‘perturbatione Gallica’), and credits Rodolfo Boncompagni Ludovisi (1832-1911, Prince of Piombino after 1883) with the decision to relocate her body from S Marta to S Ignazio. Photo: Anthony Majanlahti.

Alongside the changes to S Marta’s ownership, the final resting place of the Boncompagni nuns also changed. In 1908, the Boncompagni nuns who were originally buried at S Marta—Sister Maria Pulcheria (née Maria Boncompagni, †1648), Sister Maria Maddalena Felice (née Giovanna Boncompagni, †1688), Sister Maria Eleonora (née Caterina Boncompagni, †1699), and Sister Maria Grazia (née Cecilia Boncompagni, †1706)—were transferred to the Ludovisi family church of S Ignazio and reburied in the family crypt. S Ignazio also became the final resting place of Duchess Leanor Zapata y Brancia (†1705), the mother of the two nuns who left S Marta for that of S Lucia in Selci in 1705.

Lydia Francoeur is a second-degree student enrolled in Rutgers-New Brunswick’s School of Arts & Sciences, majoring in Philosophy. She initially graduated from Rutgers in 2021 with a double major in Accounting and BAIT, and re-enrolled part-time in September 2023 to pursue her academic passions. She hopes to continue bringing the stories of the Boncompagni Ludovisi nuns to light. She is an editor for the Areté: Undergraduate Philosophy Journal and member of Phi Sigma Tau. Outside of her academic pursuits, she works full-time as a full-time Cyber Auditor. She extends her heartfelt gratitude to Professor T. Corey Brennan for his guidance, patience, support, and enthusiasm throughout the year. She warmly thanks HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for her generosity in providing the opportunity to work on this project.

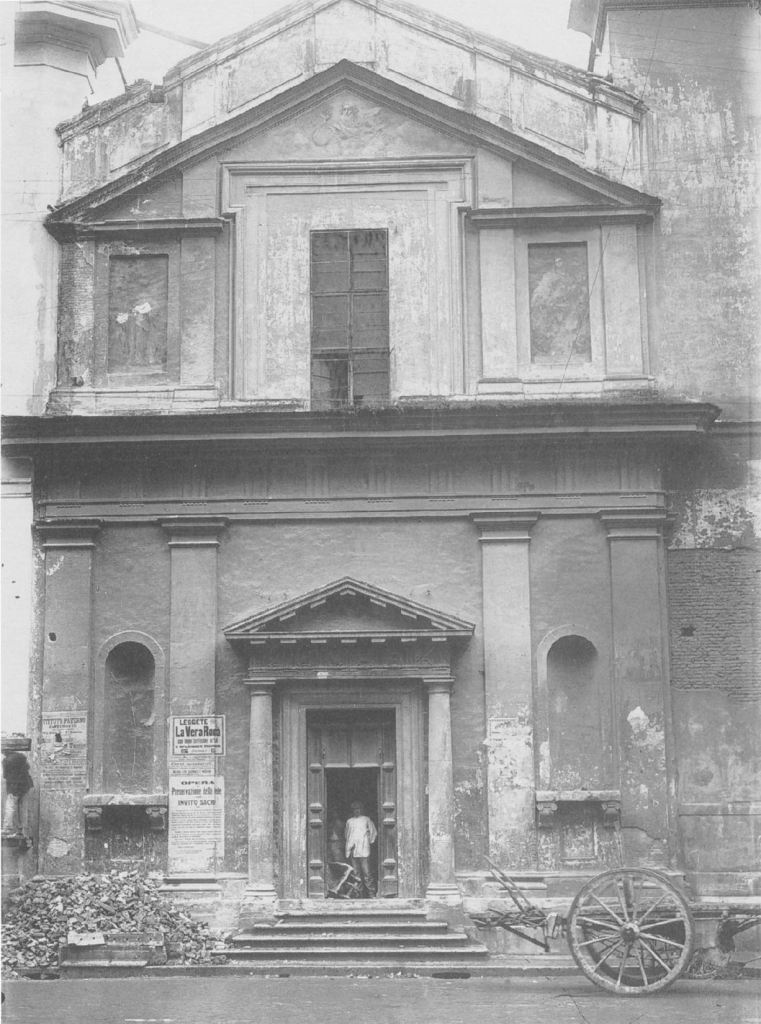

Facade of S Marta al Collegio Romano in mid-19th century. From M.R. Dunn, “Nuns as Art Patrons: The Decoration of S. Marta al Collegio Romano”, The Art Bulletin 70 (1988) 451-477, at p. 454.

Leave a comment