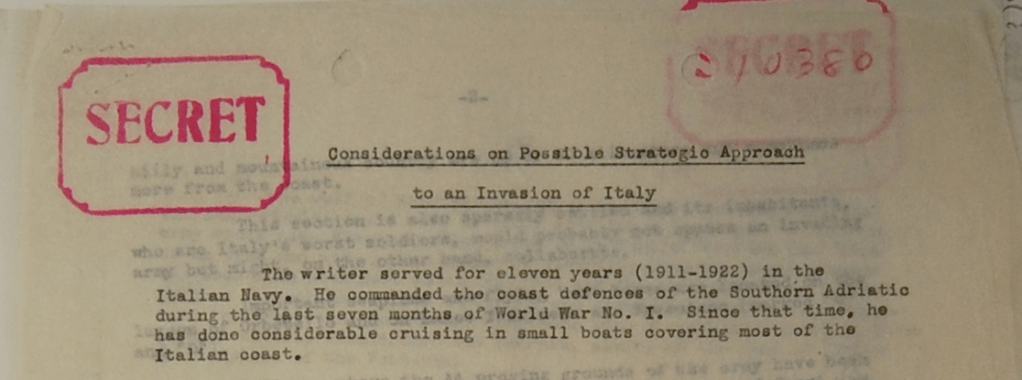

Detail from declassified OSS memo (undated, but probably late April 1943) from dossier of Prince Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi. Credit: National Archives Office of Strategic Services (Record Group 226) 1940-1947

By Brando Ajax Mazzalupi (Rutgers ’26)

In the months in which the United States moved ever closer to entering World War II, one member of the noble Boncompagni Ludovisi family was based in New York City. This was Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi (1896-1988), named after a prominent brother of his 9th great grandfather, Pope Gregory XIII (reigned 1572-1585). Of the aristocratic Boncompagni Ludovisi family—a political and cultural powerhouse that had made impressive contributions to church and Italian affairs for almost four centuries—Boncompagno was the first to take up permanent residence in the United States.

Boncompagno was born on 25 October 1896 in Rome, the second of two children of Giuseppe Boncompagni Ludovisi (1865-1930) and Arduina di San Martino di Valperga (1868-1963). His father Giuseppe was the fifth of six children—and third-born of three sons—of the family head Rodolfo Boncompagni Ludovisi and Agnese Borghese. In 1904, at age eight, Boncompagno (known familiarly as “Bonny”), and his eleven-year old sister Rosalia, had places of honor at the 50th wedding anniversary of these grandparents, Prince and Princess of Piombino since 1883.

The May-June 1938 Italian Economic Mission to Japan, with Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi (standing third from left) with Italian and Japanese industrialists. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Between May 1937 and June 1939, Boncompagno travelled back and forth between Europe and the United States at least three times, and visited also Japan, Hawaii, Canada, Cuba, and Mexico. Of these trips, the most public fell in May and June 1938, when Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi traveled to Japan and Manchuria as a technical advisor (one of about a dozen) to the Italian Economic Mission to Japan. This was a high-profile official delegation that met with every minister of Japan’s Empire, and even had an audience with Emperor Hirohito and Empress Kōjun. A LIFE magazine article of 29 January 1940 included photos of Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi as a house guest of Vincent Astor (one of the richest individuals in the world at that time) on Bermuda, along with other nobles and notables.

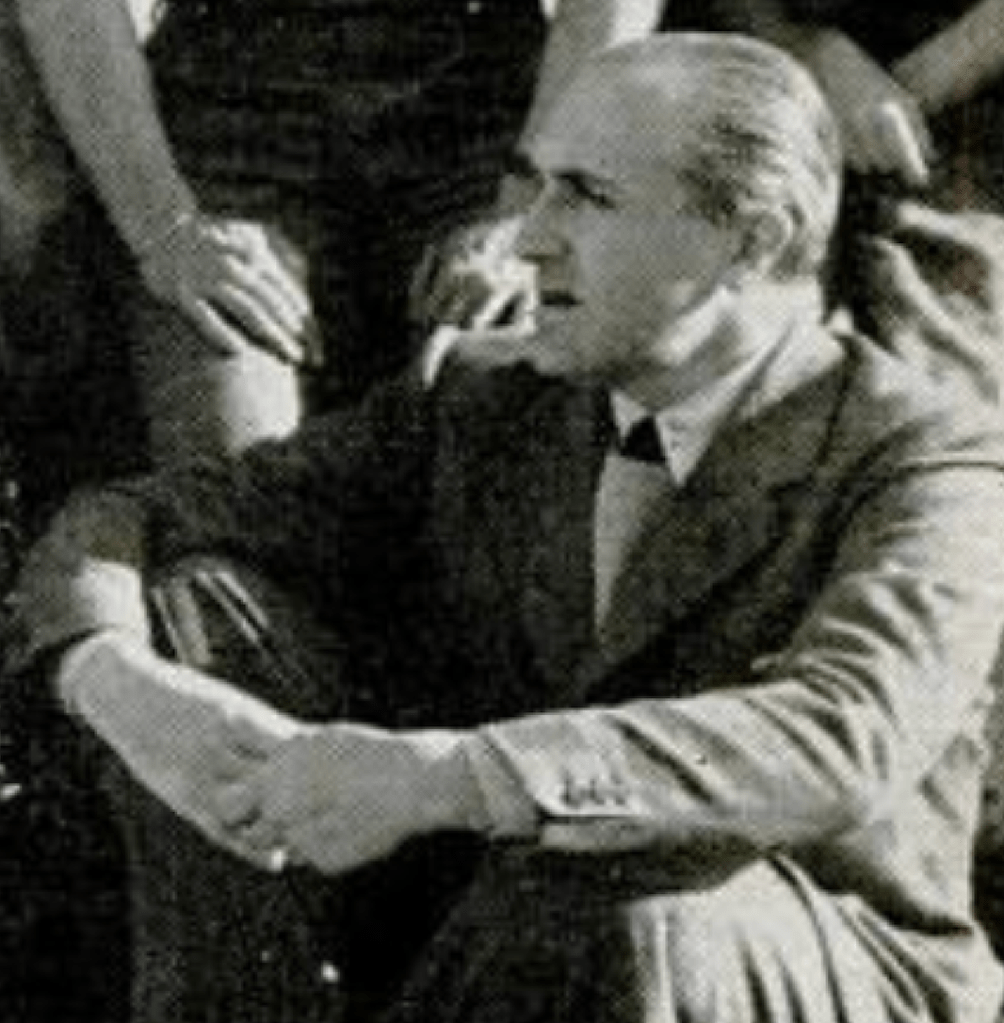

From LIFE magazine (29 January 1940), from left, Princess Scherbatow (= Adelaide Sedgwick Munroe); Vincent Astor; Katharine Drexel Dahlgren (= Mrs Oliver Eaton Cromwell); Prince Kyril Scherbatow; Selma Borger; (on ground) Prince Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi

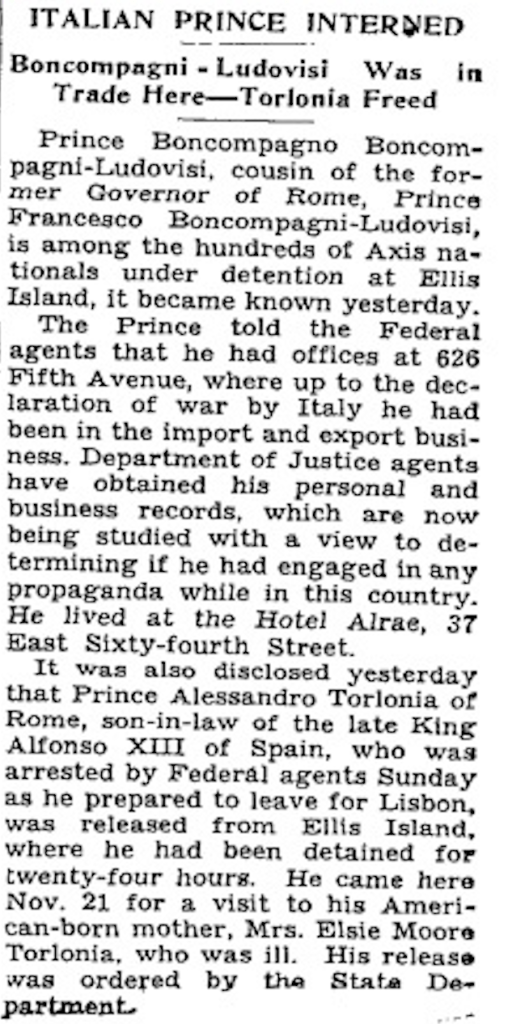

In New York City, Boncompagno lodged since later 1938 at the Alrae Hotel on 37 East 64th Street, and maintained an office at 626 Fifth Avenue, where he mainly focused on the import/export business, with a specialty in silk and rayon. However on 16 December 1941, days after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s declaration of war on the Axis powers, Boncompagno found himself amongst the hundreds of Axis nationals who were arrested and detained on Ellis Island.

Accused of being a spy and facing indefinite detention, Boncompagno soon offered to become an informer for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a predecessor to the CIA (the latter created 1947). We can trace the story in extreme detail, thanks to a hefty declassified file housed in the National Archives at College Park, Maryland. They form part of the Records of the Office of Strategic Services (Record Group 226) 1940-1947 (Entry 210; location: 250 64/21/1; CIA Accession: 79-00332A; boxes 388 and 399 [WN#15258)]).

New York Times, 16 December 1941

Boncompagno’s aim was not complete exoneration, but rather to receive parole with leave to return to Manhattan, while remaining under the custody of the OSS. For their part, it took the OSS intelligence officers a full year and many interviews to grasp precisely how Boncompagno’s noble upbringing, military experience, connections to the Italian political and financial elite, worldwide business contacts and indeed international socialite status might be useful to the Allied war effort.

On 23 January 1943 the Washington office of the OSS decided to accept Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi’s offer to cooperate. By that time, Boncompagno had been transferred to Fort Meade in Maryland. For the rest of the year, there followed an epistolary exchange between the detainee (who was eventually moved back to Ellis Island) and the OSS, represented especially by Earl Brennan, wartime head of the OSS Italian section. In almost seventy long and detailed letters on yellow legal paper, each dated and numbered, Boncompagno offers copious information regarding Fascists, industrialists, members of the Italian nobility and monarchy, as well as diplomats—even those of neutral nations. He also provides expert advice on strategic landing sites for a war campaign on the peninsula. Boncompagno seems to have made a copy or at least summary of everything he sent to Washington DC, since later letters frequently cross-reference earlier ones by date and number.

Earl Brennan (1899-1904), Head of OSS Italy and Albania Secret Intelligenc section. Credit: Special Forces Role of Honour

Finally, on 2 November 1943, Earl Brennan wrote to the Ellis Island authorities urging that Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi receive his parole. Brennan leaves his description of the precise nature of Boncompagno’s contributions deliberately vague:

“Prince Boncompagni has been of the greatest assistance to various persons in the field of immigration, alien registration, and related services”, Brennan states. “His contributions include facilitating solutions for individuals with unusual problems and rendering practical aid to the Office of Alien Enemy Control. While his own background may require clarification, he has consistently demonstrated a willingness to cooperate with federal authorities and assist in matters requiring discretion and tact.”

Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi was released from Ellis Island at some point in early 1944, and returned to his old residence at New York’s Hotel Alrae. By November of that year, he was seeking naturalization as an American citizen. Yet his letters continued, reaching a total of at least 125 by the time the Allies achieved victory in the European theater in May 1945.

There was good reason to trust Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi. Boncompagno had shared with the OSS (letter #16, 23 April 1943) that his cousin Francesco Boncompagni Ludovisi (1886-1955, Prince of Piombino after 1911), though a former Governor of Rome under Mussolini (1928-1935), harbored a “hatred of the party”—which was confirmed by his aid to Allies and Italian partisans during the war.

The OSS in its own correspondence noted that Boncompagno’s sister Rosalia (who in 1918 had married Georg Skouzes, a Greek banker) and wife Carla Borromeo Arese both had social connections with powerful Fascists, including Mussolini’s son-in-law Galeazzo Ciano, but also had the reputation of being strongly anti-Fascist, maintaining numerous ties to Britain.

It also may be that Boncompagno’s numerous letters proved vital for the Allied forces, and that they incorporated the advice in planning their invasion of the Italian peninsula that started in September 1943. What is certain is that the exchange, today held in the National Archives in College Park, is a fruitful primary source on the socio-political aspects of the ‘Ventennio Fascista’, and indeed enhances our understanding of Italian history for the whole first half of the twentieth century.

When aged not quite 16, Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi entered the Royal Italian Navy, in which he would serve for eleven years, between 1911 and 1922. As an officer, he commanded the naval defenses of the southern Adriatic coast during the last seven months of World War I. For Boncompagno, sailing wasn’t simply a matter of duty. It was one of his greatest pleasures, and in his post-service years he often cruised on yachts along the Italian coast.

Carla Boncomagni Ludovisi (née Borromeo Arese) pictured in Vogue, 22 December 1928. Photo: George Hoyningen-Huene

Boncompagno became engaged to the Milanese aristocrat Carla Borromeo Arese (1897-1987) during his war service, and they married on 14 June 1917. Borromeo and Boncompagni Ludovisi had a daughter, Anna, in 1923. During the years of World War II, both mother and daughter lived in Switzerland, in Lausanne with summer sojourns to St. Moritz. An OSS report from January 1943 describes each as in poor health. Indeed, Anna would tragically pass away at the age of 23 in 1946. Boncompagno’s marriage with Carla Borromeo Arese lasted until 1947 when they mutually agreed to divorce.

In the post-war period, Boncompagno remained in the United States, and on 29 November 1947 he married Emilie Selma Borger in Reno, Nevada. Borger was born in Vienna in 1901, where she married in 1922 but later divorced. She had been a permanent resident of the United States since 1938, and applied for naturalization in 1939. Borger had joined Boncompagni Ludovisi in Japan when he participated in Italy’s Economic Mission in May and June 1938; the two sailed together from Yokohama to Honolulu, and then to Los Angeles. The 1940 US census shows Borger living, like Boncompagni Ludovisi, at the Alrae Hotel on 37 East 64th Street. Like Boncompagno, at the start of WW II she was held in custody on Ellis Island, at least for some of 1942. OSS reports from 1942 plainly call Borger the mistress of Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi. After marrying, the couple lived in New York City until their deaths, with Boncompagno dying on 5 May 1988, aged 91, soon followed by Selma Borger on 29 July 1989, at the age of 87.

Now that a brief biography of Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi has been established, we can turn to the contents of the epistolary exchange between him and Earl Brennan of the OSS Italian section. Though mainly limited to the year 1943, the dossier contains over six hundred pages. It touches upon a wide variety of topics, including military and strategic advice, and information on key political and industrialist figures within Mussolini’s regime, as well as the anti-Fascist resistance.

One unusually prominent individual who stands out within the correspondence is Umberto of Savoia (b. 1904), the Prince of Piedmont, the only son of Italy’s King Vittorio Emanuele III (1869-1947, reigned 19 July 1900-9 May 1946) and Queen Elena of Montenegro (1873-1952). As Umberto II, this man would be the last King of Italy, reigning just 34 days, from 9 May until his deposition on 12 June 1946. Boncompagni Ludovisi mentions the Prince of Piedmont in just three of his many letters. However, through his characterization, Boncompagno offers interesting insights on the future Umberto II, including his liberal and progressive proclivities amidst the oppressive Fascist environment of the ‘Ventennio.’

“The visit of the Prince of Piedmont [= Umberto of Savoia] to one of our naval bases”, L.U.CE. newsreel (C0201) 12 January 1941

Boncompagno mentions Umberto first in his letter #4, of 23 January 1943, which offers a long summary list of his impressions of various Italian elites. There his purpose is only to underline the importance of the figures whose political attitudes he is describing. Count Luchino Visconti di Modrone (1906-1976), the famed film director, is described as a “good friend of Prince Umberto.” His cousin Count Ottorino Visconti (1909-1978), here identified as “a businessman residing in Switzerland”, but who acted in Italian films in the late ‘30s, is also a “friend of Prince Umberto.” Duke Riccardo de Sangro (1879-1968), described as a 52-year-old Italian diplomat stationed in Buenos Aires, is listed as “an adjutant and friend to Prince Umberto.”

Much more fulsome is Boncompagno’s communication of 25 April 1943 (“my 19th letter”), where he emphasizes Prince Umberto’s close connections to the liberal, “anti-fascist bourgeoisie,” including the “Visconti boys.” Out of the Visconti, Prince Umberto was very close to “Count Luchino Visconti di Modrone” an “intelligent gentleman with money”, inherited from his parents who owned what is said to be Italy’s largest pharmaceutical factory. Boncompagno continues: “I never heard that he was interested in politics, but I know that he was very much interested in race-horses”, and had stables near the Cappannelle race track “near Rome” (actually, in the province of Arezzo in southeastern Tuscany).

First-day cover for Italian postage stamp (13 October 2006) marking the centenary of the borth of film director Luchino Visconti

It emerges from this letter that Boncompagno had been asked to comment on a nameless informer’s report about anti-Fascist meetings at two Visconti homes in or near Rome. Fortunately, the report is found in the dossier, dated 16 September 1942, under the heading “Visconti, Count Lucini” [sic].

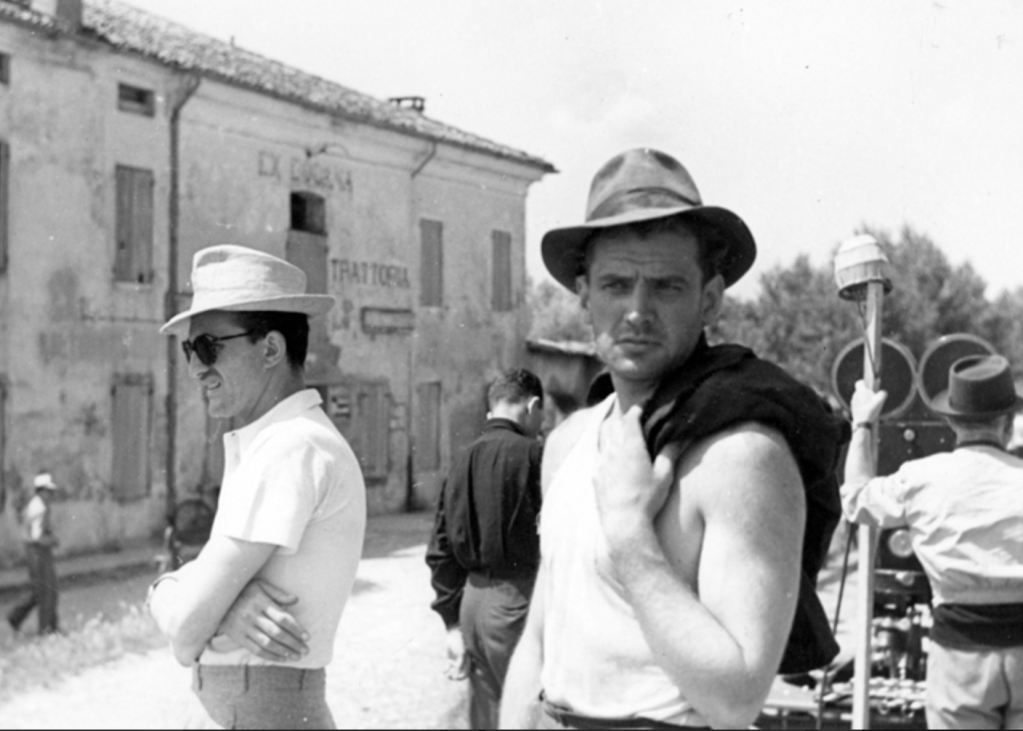

In essence, the informer alleged that Luchino Visconti’s home in Rome, termed “a remote villa”, formed a hub for opposition to Mussolini’s regime. It hosted a clandestine radio, set to listen to broadcasts from London; a dissident group conversed there on the progress of the war and the personalities of Mussolini’s government. Prince Umberto reportedly visited the villa every three days. Of the dozen other regular attendees from Rome and Milan that are named, some are identifiable, such as the film actor Massimo Girotti (1918-2003), who co-stars in Visconti’s 1943 directorial debut Ossessione. Others are not, for instance, an alleged son of the composer Giacomo Puccini named ‘Mario’. The group is said to have been staunchly pro-British and critical of Mussolini’s reign. Prince Umberto is explicitly identified in the informer’s report as a fierce critic of Mussolini.

On the set of Ossessione (1943), director Luchino Visconti and actor Massimo Girotti, each mentioned in the OSS correspondence between Earl Brennan and Boncompagni Boncompagni Ludovisi. Photo: Osvaldo Civirani

The informer also identified a second gathering place in Rome for this opposition group, namely the home of Luchino’s cousin Ottorino Visconti. Ottorino, says the informer, was arrested in May 1942—it seems that Fascist authorities knew about his opposition activities—but, thanks to Prince Umberto’s personal intervention, was then held in relative comfort in a private residence in Como, near the Swiss border.

In response to this report, Boncompagno wrote in his 25 April letter that “Prince Umberto was always a friend of the Visconti boys, so it seems very likely that he visited often Luchino.” He confirms that Milan—along with Torino and Livorno—formed anti-Fascist centers in Italy, and so credits the detail that residents of the city travelled to the Rome residence of Luchino Visconti. “And I believe”, he continues, “what the informant reports about Visconti’s guests’ conversations and opinions about the Germans, Ciano [= Mussolini’s son-in-law], Prince Umberto, and the people in Italy.” Many of the reported guests are unknown to Boncompagno, but he does recognize Puccini’s alleged son: “he is a bum with lots of money and I could know everything about him from a man in New York.”

Boncompagno found aspects of the second part of the informer’s memorandum unconvincing. “I would not give much credit to the people meeting at Ottorino Visconti’s house. He is a homosexual who lives exclusively in the society of that kind of fellow.” However, Boncompagno conceded “it is very probable that Prince Umberto helped Ottorino out of prison; Prince Umberto had always many friends among homosexuals.” He continues, “if you are interested to know something about Prince Umberto, I suggest you the following chanel [sic] which you could easily use: Duca Riccardo de Sangro, 52 years old, is an adjutant (and a friend) to Prince Umberto”, and presently was serving in the Italian embassy in Buenos Aires.

The important part of the evidence here is that Boncompagno takes for granted Prince Umberto’s close connections to dissident elites, along with his support and patronage of homosexuals, and likelihood of attending secret meetings that focused on the criticism of Mussolini’s government. This in turn supports the notion that the heir-apparent to Italy’s kingdom had anti-Fascist beliefs and tendencies.

King Vittorio Emanuele III with his son Umberto, the Prince of Piemonte., ca. 1944 On 5 June 1944, the day after the Liberation of Rome, the King made his son de facto head of the Kingdom, naming him Lieutenant General of the Realm. Credit: Arkivi UG

The third of Boncompagno’s three letters where he mentions Umberto is the briefest, but illuminating all the same. On 4 November 1943 (“my 66th letter” to the OSS), Boncompagno emphasizes that Italy’s Freemasons opposed both King Vittorio Emanuele III and his son Umberto, though for different reasons. The King, Boncompagno explains he had heard in his youth, was originally a Freemason, “brought up by a free-mason and anti-Catholic tutor, General Orio”, but as king allowed Freemasons to be persecuted, and so was viewed as a “traitor”. Umberto for his part is “very strongly Catholic” and as such, we are told, was unacceptable to Freemasons. Boncompagno continues, “one cannot say that Prince Humbert [= Umberto] sympathized with Fascism, but one can rather reproach his lack of efficiency and of popularity, for his reputation of being a play-boy”.

Extant literature on Prince Umberto amply supports Boncompagno’s characterization of the future king’s political tendencies, for which he provides concrete instances. For example, Denis Mack in Italy and its Monarchy (1989, p331) states that while “Umberto’s political views were flat and conventional,” he was by no means a “reactionary” and wanted to make Italy “genuinely democratic”. Mack’s assessment of Umberto II supports Boncompagno’s characterization, including Umberto’s anti-Fascist and liberal proclivities.

Daily News (New York City), 16 December 1941

A crucial question remains: is Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi a reliable source on his contemporary politics and personalities? Boncompagno (letter #19, 25 April 1943) does give his “assurance” that the “informations or opinions” provided are “impartial and not influenced by any personal reason or ambition.” He further states that he is “only interested in the USA winning the war and the best durable peace.” He did not, for example, ask to travel back to Italy; indeed, on the conclusion of war, he took US citizenship and resided in New York City until the end of his life. While Boncompagno’s assurances could be genuine, there is undoubtedly a subtle comical undertone to his statements, given that he was divulging this information while in custody of the United States OSS and desperately seeking release from confinement and parole.

From the OSS perspective, cooperation with Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi posed a dilemma. An officer’s report from 3 September 1942, before the epistolary exchange with Washington DC was encouraged, sums up the difficulties of the situation: “Boncompagni, of course, is dynamite. If he is on the level, he can be our most valuable contact. If he is playing double, he can cause us a great deal of difficulty.”

One thing seems certain. The World War II dossier for Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi is so lengthy and so rich in detail that further study and analysis is bound to yield valuable results, at the least for gauging how a member of Rome’s highest nobility understood the “Ventennio” and envisaged Italy’s post-Fascist future.

Brando Ajax Mazzalupi is a rising senior in Rutgers University-New Brunswick’s School of Arts & Sciences, double-majoring in History and Philosophy along with minoring in Political Science. Brando is an international student originally from Rome, Italy. This last spring Brando was inducted in two honor societies: Phi Alpha Theta, which is the national honor society in History, and Phi Beta Kappa, the oldest academic honor society in the United States. During the academic year 2024/25, Brando interned with the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi as an Aresty Undergraduate Research Assistant under the guidance of Professor T. Corey Brennan. Brando adds “I’m extremely grateful to Professor T. Corey Brennan and the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi for allowing me to embark on this research journey, furthering my understanding of the discipline and of my hometown. I would like to thank Professor Brennan for his guidance, availability and feedback, which have helped me hone my archival and research skills. I also would like to thank Christina Lee (Rutgers ’16) for images of the OSS dossier in the National Archives, and HSH Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for encouraging this historical research.

Detail of photo from LIFE magazine 29 January 1940: Prince Boncompagno Boncompagni Ludovisi

Leave a comment