Portrait of Giacinta Orsini Boncompagni Ludovisi, Duchess of Arce, by Pompeo Batoni (1758). Private collection (auctioned 1997). Credit: https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-306136

By Sarah Freeman (University of Pennsylvania ’29)

Giacinta Orsini Boncompagni Ludovisi died on Saturday 9 June 1759, around three in the afternoon. Her life makes for a compelling story, one that I have detailed in a previous post. She was born in Naples on 9 August 1741; her parents on each side were descended from distinguished Papal noble families. Giacinta’s father was Don Domenico Orsini d’Aragona, the 15th Duke of Gravina, and her mother Princess Anna Paola Flaminia Odescalchi. Giacinta’s mother passed away in 1742 while giving birth. A year later, shortly after Giacinta’s second birthday, her widower father was appointed a Cardinal.

Giacinta was a gifted poet, musician, and scholar. She was elected to the renowned Academy of the Arcadians at just 13 years old, where (with the pen name ‘Euridice Aiacidense’) she was deeply admired for her intelligence, kindness, and religious piety. Her marriage at age 15 in July 1757 to Antonio (II) Boncompagni Ludovisi (1735-1805, head of family after 1777) was seen as a happy union, and her early death was mourned as a great loss by all who knew her. She was just 17 years and 10 months old when she passed.

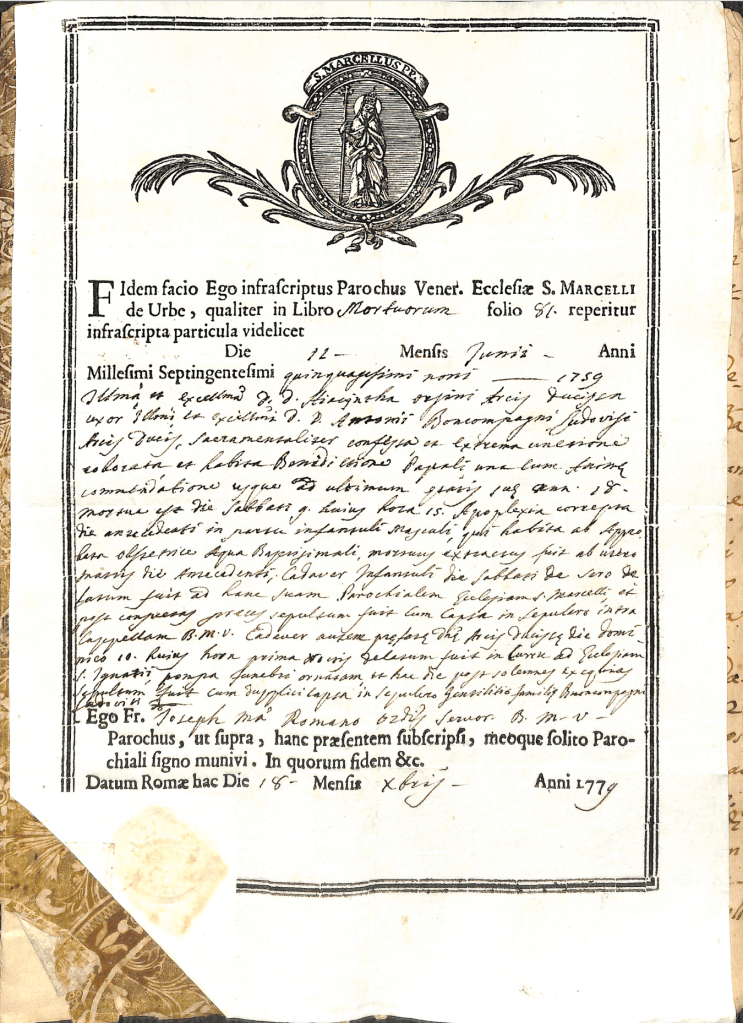

Certification (18 December 1774) by parish priest of S Marcello sul Corso of death of Giacinta Orsini Boncompagni Ludovisi while giving birth to a son, 9 May 1759. Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 592 no. 32; courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

Giacinta’s death certificate, as well as her epitaph in the Boncompagni Ludovisi crypt in the church of S Ignazio in Rome (see below for its text) states she died giving birth to a son. Her funeral in Rome reflected both the sorrow of her early death and the immense wealth and devotion of her noble birth and marriage families. From the moment of Giacinta’s passing, preparations began to honor her short life in the grandest way possible.

From an unpublished 1795 biography of Giacinta Orsini by Carlo Rosa aka ‘Somasca‘ (see my previous post), we already knew the basic outlines of her funeral. Somasca mentions the date of her death, where she died, where the funeral was held, and records her epitaph. However, a dossier of documents in the Boncompagni Ludovisi family archive in the Casino dell’Aurora goes much deeper and sheds new light on the celebration of Giacinta’s life, allowing us to better recreate this tragic event.

Masses were ordered immediately—over 800 in total would eventually be said. Her body was first exhibited where she had died, in the Palazzo of the Mellini family on the Corso next to the Church of S Marcello in Rome. By 7 p.m., Giacinta’s corpse was dressed in a Franciscan nun’s habit, which not only emphasized her piety but also reflected the idealized image of virtue placed upon young noblewomen in Catholic society. The rest of the display was extravagant. She was next placed in a second antechamber in the palace, surrounded by rich damask and velvet cloths trimmed with gold, as well as four temporary altars. Her head and face were left uncovered for mourners to see.

Religious figures kept vigil in rotating shifts. Groups of ten prayed to the Office of the Dead continuously, and religious women from local communities were allowed into the home to remain at her side in prayer. Her household followed strict schedules to ensure unbroken attendance. The mourning process can be characterized as formal, intense, and deeply ritualistic.

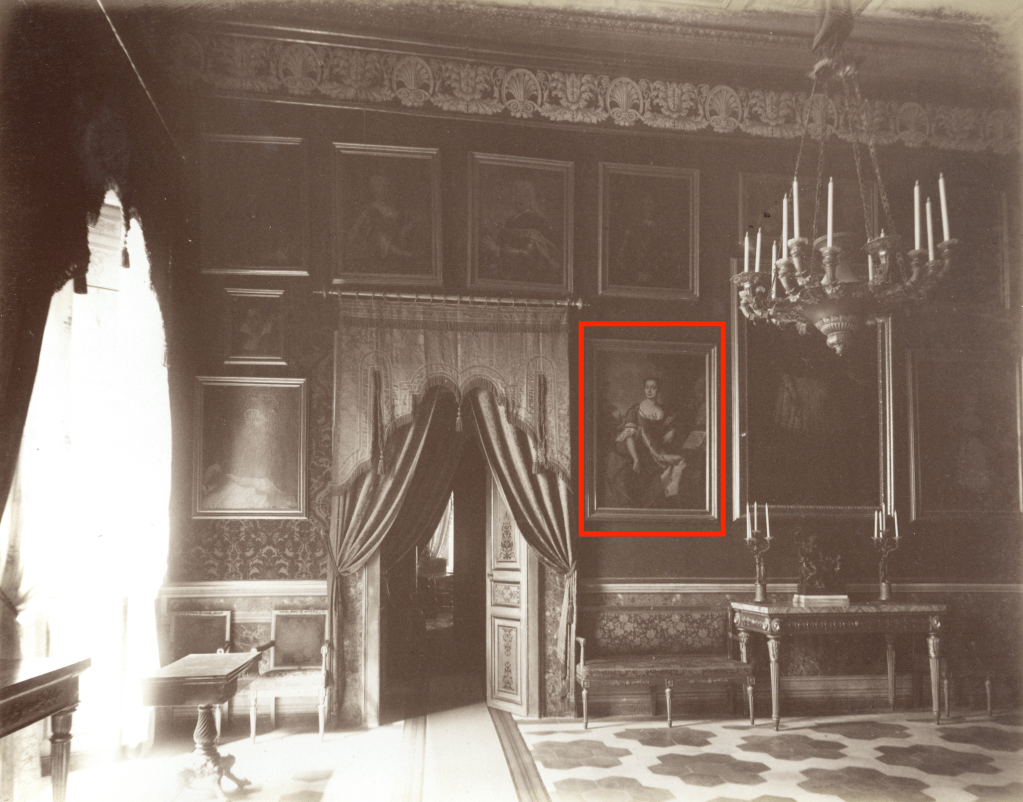

Portrait of Giacinta Orsini (outlined in red) exhibited in a grand sala of the Palazzo Piombino on Rome’s Piazza Colonna, demolished in 1889. Image courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

Our memorandum offers an unusual detail about the conditions of this viewing in the Palazzo Mellini. “Throughout the entire day, the body was left on display to the public, which gathered in great numbers; and given the excessive heat, which raised concern of decomposition, at 7 p.m. it became necessary to place the body in a cypresswood coffin, covered with…cloth, and so it remained on display until the evening.”

Very early on Monday 11 June, around 1:30 am, her coffin—made of cypress wood and lined in even richer fabric—was moved to the nearby Church of S Ignazio. It was transported in a satin-draped noble carriage, “preceded by 14 footmen dressed in mourning, carrying lit wax torches, and two others with pitch torches”. Soon after, more carriages followed with additional mourners, with the nearest three carrying officiants for the funeral. Upon arrival, Giacinta was received with a full ceremony. The exterior of S Ignazio was decorated, and the interior of the church was dressed with embroidered damask, silver candlesticks, and tall candles. Eighty torches, now extinguished, were laid beside her. Fans printed with her coat of arms were placed throughout the space.

In the same dossier in the Casino dell’Aurora, there are funeral expenses listed for two other members of the Boncompagni Ludovisi family that help us contextualize the honors paid to Giacinta Orsini. The first is from the previous generation: Ippolita Ludovisi (1663-1733), the first of her family to marry into the Boncompagni, though each was from Bologna and boasted a Pope. A major figure in her time, Ippolita reigned as Princess of Piombino after the death of her husband in 1707, and played a significant role in larger Italian noble society.

These records also include the arrangements that followed the death in 1767 of a young child: four-year-old Anna Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi (born 5 March 1763), a daughter of Antonio (II) after his remarriage in 1761 to Vittoria Sforza Cesarini. What’s especially striking is the number of Masses commissioned for each of their funerals. For Giacinta, over 800 Masses were celebrated across Rome—beginning immediately, continuing daily, and lasting from early June through August. In contrast, Ippolita’s funeral in 1733 included just 200 Masses over the course of two days, with no additional services mentioned. For the young Anna Eleonora, who died in 1767, the memorial doesn’t specify any Masses at all. This contrast highlights just how elaborate and spiritually intensive Giacinta’s funeral was. It’s clear that she had a deep impact on those around her—being highly celebrated within her community.

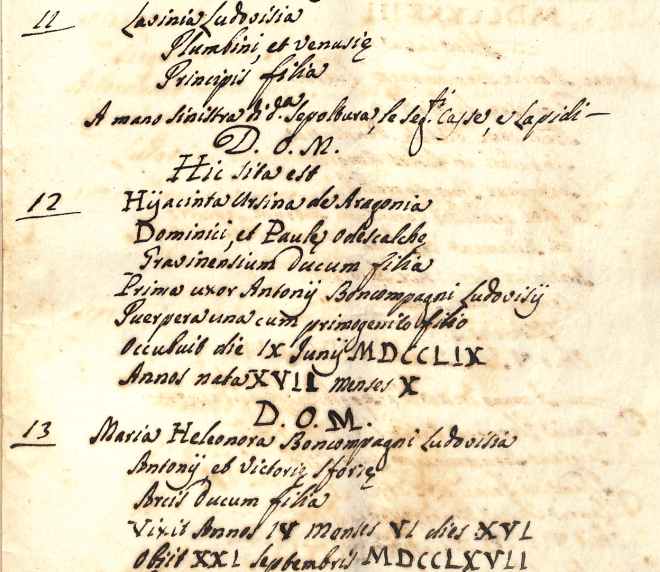

Detail of late 18th century transcription of funerary epitaphs in the Boncompagni Ludovisi family crypt in S Ignazio, with nos. 12 (1757) and 13 (1767) discussed in this article. Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 592 no. 32; courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

Nonetheless, Giacinta’s funeral wasn’t just about honoring her life—it was about preserving an image. Everything from the prayer schedule to the decorative fans carrying her arms was meant to showcase devotion, grief, and prestige. The price tag reflected that: expenses for music, coffins, clothing, and ceremony exceeded 1150 scudi. In contrast, the funeral expenses for Ippolita Ludovisi in December 1733 were 60.55 scudi, and that for the child Anna Eleonora Boncomopagni Ludovisi in 1767 cost 84.25 scudi.

As Cristina Parretti highlights in her article “The Portrait of Giacinta Orsini Boncompagni Ludovisi by Camillo Loreti in the Museum of Rome,” Giacinta’s image was carefully curated. For example, Carlo Goldoni (1707–1793), the famed Venetian poet, had dedicated his 1758 comedy La Vedova Spiritosa (The Witty Widow) to her, calling her (despite her age) his “patroness.” Giacinta was, as Goldoni put it, “well-known in Rome, in Italy, and beyond: her name was known to the world.” Her funeral only added to that reputation. As a poet, a cherished member of the Arcadians, and a symbol of everything a noblewoman was supposed to be, her memory wasn’t just honored—it was crafted, both while she was alive and even after she was gone.

Giacinta’s funeral was a spectacle, but one that reveals the expectations placed upon her: to be pure, devout, and mourned with ritual precision. In death, she became the perfect image of the noblewoman she was in life.

What follows below is a transcription of the narrative portions of the detailed dossier in the Casino dell’Aurora (Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 592 no. 32) that describes the three funeral services, of Ippolita Ludovisi (1733), Giacinta Orsini (1759), and young Anna Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi (1767).

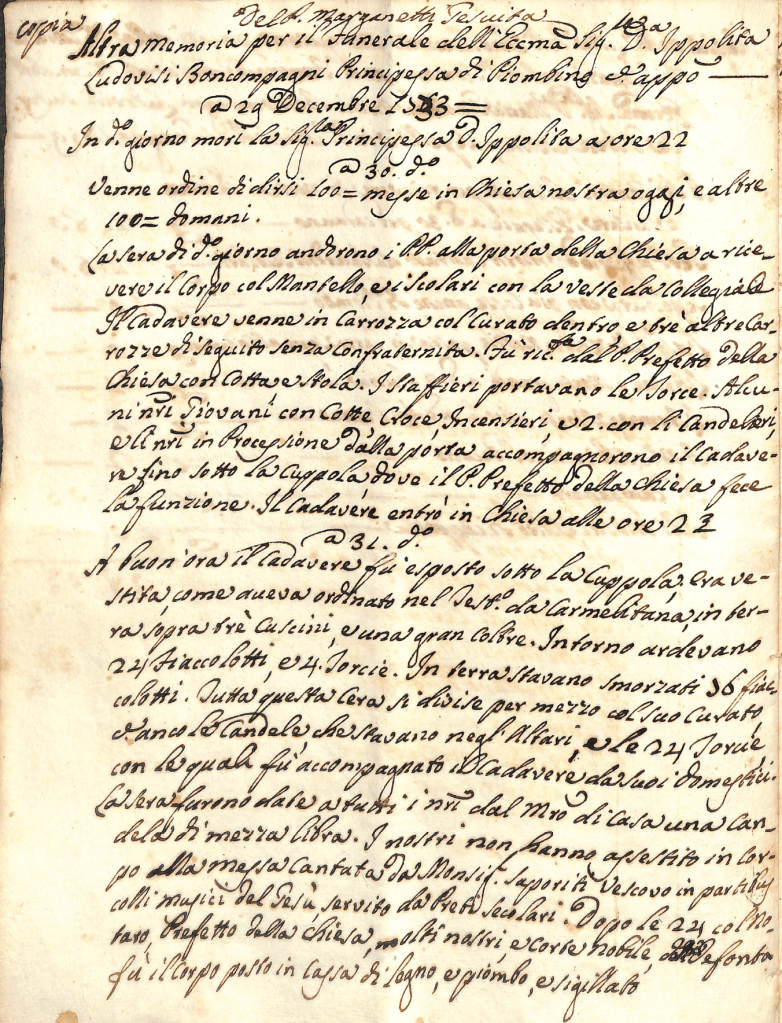

Copy of memorandum of funeral arrangements for Ippolita Ludovisi (1663-1733), Princess of Piombino. Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 592 no. 32; courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

I (1733). Memorandum for the funeral of the Most Excellent Lady Donna Ippolita Ludovisi Boncompagni, Princess of Piombino, etc. [Written by] the priest Marganetti, Jesuit.

29 December 1733: on this day, the Lady Princess Donna Ippolita died at 10 p.m.

30 December: An order was given for 100 Masses to be said in our Church today, and another 100 tomorrow.

In the evening of the same day, the Fathers went to the church door to receive the body, wearing mantles, and the students in their collegial robes. The corpse arrived in a carriage, with the parish priest inside, and three other carriages following, without a confraternity. It was received by the Prefect Father of the Church, wearing surplice and stole. The footmen carried torches. Several young members in surplices, with the cross, incense-bearers, and two with candlesticks, and our members in procession from the entrance accompanied the body to beneath the dome, where the Prefect Father of the Church performed the ceremony. The body entered the church at 10 p.m.

31 December: Early in the morning, the body was laid out beneath the dome, dressed, as she had ordered in her will, in the habit of a Carmelite nun, on the ground upon three cushions and a large covering. Around her burned 24 large torches and 4 smaller torches. On the ground lay extinguished 76 torches. All this wax was divided equally with her parish priest etc. Also the candles that were on the altars, and the 24 torches with which the body had been accompanied by her servants. In the evening, each of the members [of the Society of Jesus] was given by the Master of the House a candle of half a pound. Our members did not attend in full body the sung Mass celebrated by Monsignor [Giuseppe] Saporiti, bishop in partibus [i.e., titular bishop], with musicians from the Gesù [Church], served by secular priests.

After midnight, with the notary, the Prefect of the Church, many of our members, and the noble court of the deceased, the body was placed in a wooden and lead coffin and sealed.

Memorandum (page 1 of 3) of funeral arrangements for Giacinta Orsini Boncompagni Ludovisi (1741-1759). Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 592 no. 32; courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

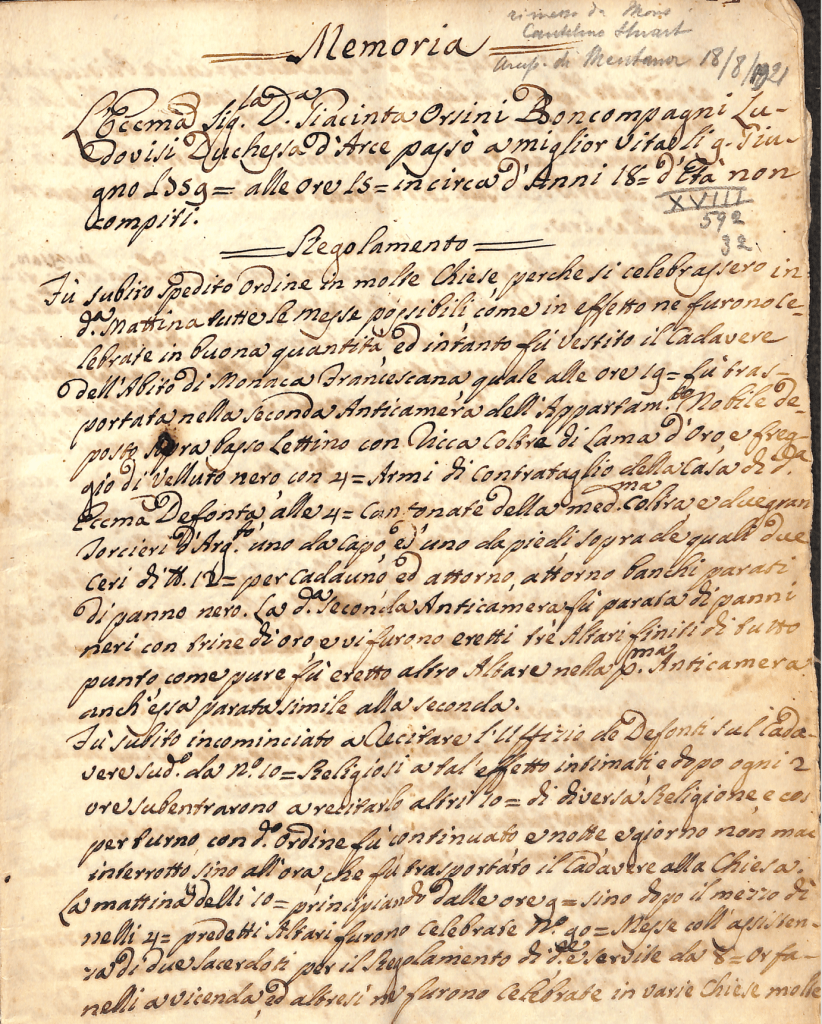

II (1759). Memorandum. The Most Excellent Lady Donna Giacinta Orsini Boncompagni Ludovisi, Duchess of Arce, passed to a better life on 9 June 1759 at 3 p.m., at about 18 years of age, not yet completed.

Arrangements: Orders were immediately dispatched to many churches so that as many Masses as possible could be celebrated that morning; indeed, a good number were celebrated, and in the meantime the body was dressed in the habit of a Franciscan nun. At 7 p.m. [on 9 June], it was transported to the second antechamber of the noble apartment, laid upon a raised bier with a rich gold-threaded coverlet and black velvet trim, with four heraldic arms embroidered in relief of the house of the said Most Excellent Deceased. At the four corners of this coverlet stood two large silver candlesticks, one at the head and one at the feet, each bearing candles 12 ounces tall, and surrounding it, benches draped in black cloth. The said second antechamber was draped in black cloth with gold lace, and three fully furnished altars were erected there, as well as another altar in the same antechamber, also decorated in the same style as the second.

The Office of the Dead was immediately begun to be recited over the said body by 10 religious, summoned for this purpose, and every two hours another 10 from different religious orders took their turn, and thus this rotation continued unceasingly day and night until the time when the body was carried to the church.

On the morning of the 10th [of June], beginning at 9 a.m. and lasting past midday, at the 4 aforementioned altars [in the Palace antechamber] 90 Masses were celebrated, assisted by two priests with the service regulated by 8 orphan boys in turn. Likewise, hundreds more were celebrated in various churches, including 4 by name in the 4 privileged Churches. [Hard to identify, in addition to S Marcello sul Corso and S Ignazio.]

Memorandum (page 2 of 3) of funeral arrangements for Giacinta Orsini Boncompagni Ludovisi (1741-1759). Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 592 no. 32; courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

Throughout the entire day, the body was left on display to the public, which gathered in great numbers; and given the excessive heat, which raised concern of decomposition, at 7 p.m. it became necessary to place the body in a cypresswood coffin, covered with the aforementioned cloth, and so it remained on display until the evening.

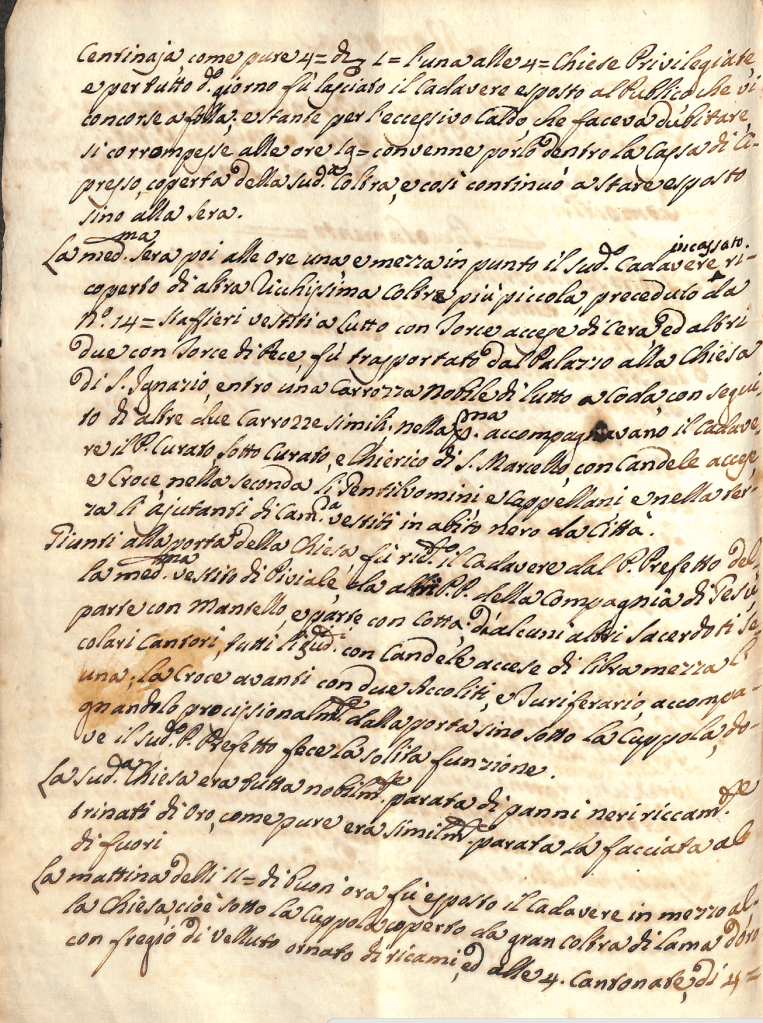

That same evening, at precisely half past one, the said encased body, covered with another even richer and smaller cloth, preceded by 14 footmen dressed in mourning, carrying lit wax torches, and two others with pitch torches, was transported from the [Mellini] Palace to the Church of S Ignazio, in a noble mourning carriage with a train, followed by other similar carriages. In the nearest one accompanying the body were the parish priest, the assistant priest, and a cleric of S Marcello, with lit candles and the Cross; in the second carriage were the Gentlemen and Chaplains; and in the third, the chamber attendants dressed in black city attire.

When they reached the church doors, the body was received by the Prefect Father of the church, wearing a cope, along with other Fathers of the Society of Jesus, some in mantles and some in surplices; other priests were singers and scholars, all of them holding lit candles weighing half a pound each. The cross preceded the procession with two acolytes and an incense-bearer, and the aforementioned Prefect Father led the customary rite.

The said church [of S Ignazio] was entirely splendidly adorned with the richest fabrics, and gold trimming, and the façade outside was similarly decorated.

On the morning of the 11th [of June], early, the body was laid out in the center of the church beneath the dome, covered with a large gold-threaded cloth with velvet trim adorned with embroidery, and at the four corners were four heraldic crests in raised embroidery of the Most Excellent Deceased, and four fans with the same coats of arms, surrounded by 20 clusters of wax, totaling 80 large extinguished torches, and two silver candlesticks, one at the head and the other at the feet, each bearing torches measuring 22 ounces.

Memorandum (page 3 of 3) of funeral arrangements for Giacinta Orsini Boncompagni Ludovisi (1741-1759). Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 592 no. 32; courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

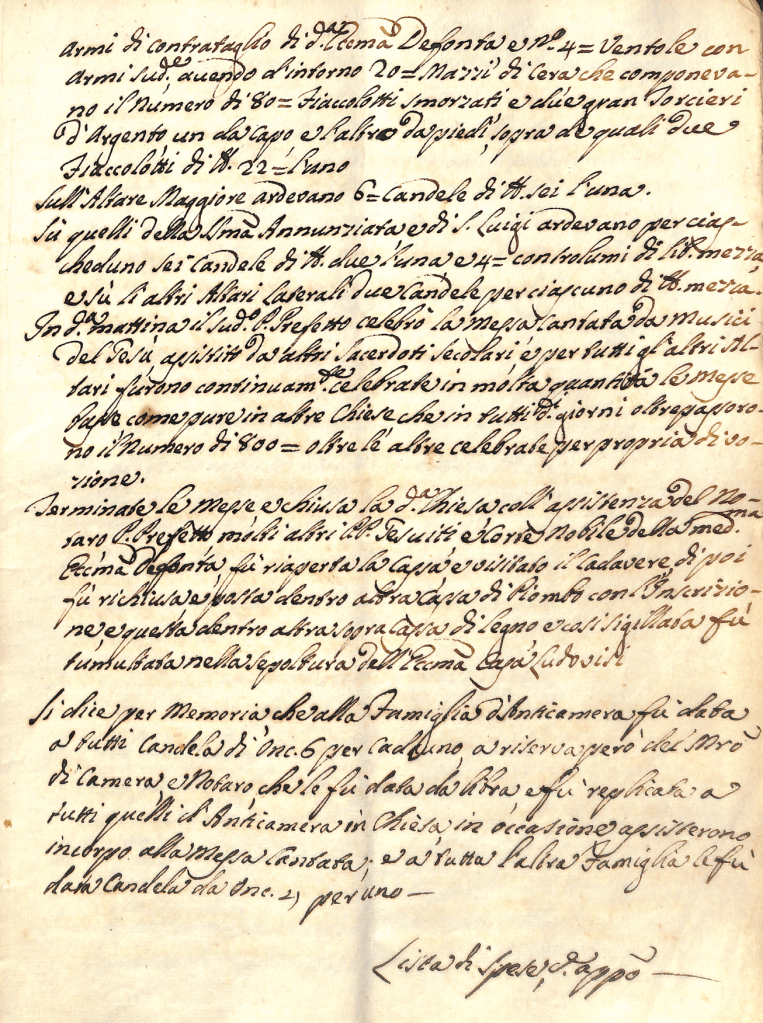

On the high altar burned six candles, each 6 ounces in weight.

On the altars of the Annunciation and of S Luigi, six candles burned on each, each 2 ounces in weight, and 4 secondary lights (?) of half a pound. On the other side altars, two candles each, each of ½ ounce.

That morning, the aforementioned Prefect Father celebrated the sung Mass with music from the Church of the Gesù, assisted by other secular priests, and at all the altars, Masses were celebrated continuously and in great number, as well as in other churches, which over the course of all the days exceeded 800 Masses, not including those celebrated out of personal devotion.

Once the Masses had ended and the church was closed, in the presence of the notary, the Prefect Father, many other Jesuit Fathers, and the noble court of the Most Excellent deceased, the coffin was reopened and the body inspected, then it was closed again and placed inside another lead coffin with an inscription, and this placed within another outer wooden coffin, and thus sealed, it was entombed in the burial vault [in S Ignazio] of the Most Excellent House of Ludovisi.

It is recorded for memory that each member of the antechamber staff was given a 6-ounce candle, except for the master of the chamber and the notary, who each received a 1-pound candle. The same was distributed again to all those of the antechamber who attended the sung Mass in full; and to all other household members, a 2-ounce candle was given to each.

Memorandum (page 1 of 2) of funeral arrangements for Anna Maria Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi (1763-1767). Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 592 no. 32; courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

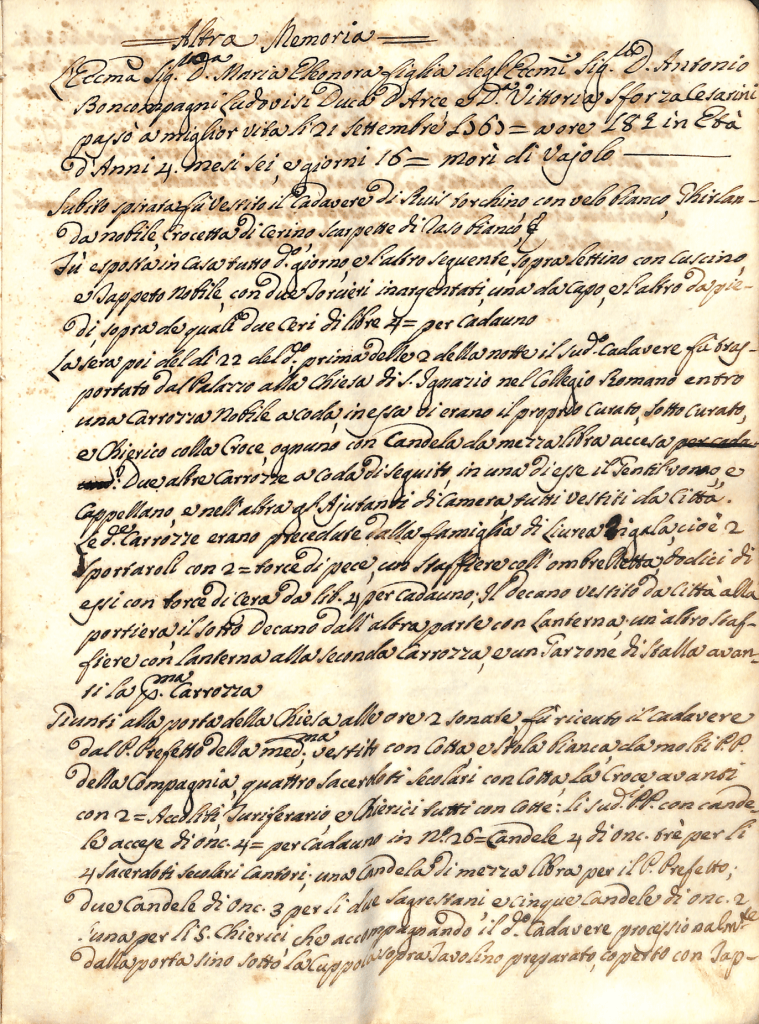

III (1767). The Most Excellent Lady Donna [Anna] Maria Eleonora, daughter of the Most Excellent Lord Don Antonio Boncompagni Ludovisi, Duke of Arce, and Donna Vittoria Sforza Cesarini, passed to a better life on 21 September 1767 at 6 p.m., at the age of 4 years, 6 months, and 16 days – she died of smallpox.

Immediately after her passing, the body was dressed in a dark crimson robe with a white veil, a noble garland, a small wax cross, white satin shoes, etc.

She was laid out in the house throughout that day and the next, upon a small bed with a pillow and a noble carpet, with two silvered candlesticks, one at the head and the other at the feet, on which were placed two candles, each weighing 4 pounds.

In the evening of the 22nd [of September], before 2 a.m., the aforementioned body was transported from the Palace [?i.e. Mellini, on the Corso] to the Church of S Ignazio at the Collegio Romano in a noble carriage with a train. In it were the parish priest, the assistant priest, and a cleric with the Cross, each carrying a lit half-pound candle.

Two other carriages with trains followed; in one was the Gentlemen and Chaplain, and in the other the chamber attendants, all dressed in city clothes.

These carriages were preceded by the household in liveried dress: that is, 2 torchbearers with 2 pitch torches, a footman with a small umbrella, twelve of them with wax torches of 4 pounds each, the Dean dressed in city clothes at the front gate, the Sub-Dean on the other side with a lantern, another footman with a lantern at the second carriage, and a stable boy in front of the same carriage.

Memorandum (page 2 of 2) of funeral arrangements for Anna Maria Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi (1763-1767). Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 592 no. 32; courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

Arriving at the church doors at the stroke of 2 a.m., the body was received by the Prefect Father of the church; dressed in surplice and white stole, along with many Fathers of the Company, four secular priests in surplices, the Cross preceding with 2 Acolytes, a thurifer, and clerics all in surplices.

The said Fathers held candles weighing 4 ounces each, numbering 26. Four 4-ounce candles were for the 4 secular priest singers; a half-pound candle for the Prefect Father; two 3-ounce candles for the two sacristans, and five 2-ounce candles, one for each of the clerics who accompanied the said body in a procession from the door to beneath the dome, where a prepared table covered with a noble carpet had been set. There, the said Prefect Father with the singers and Fathers performed the usual rites.

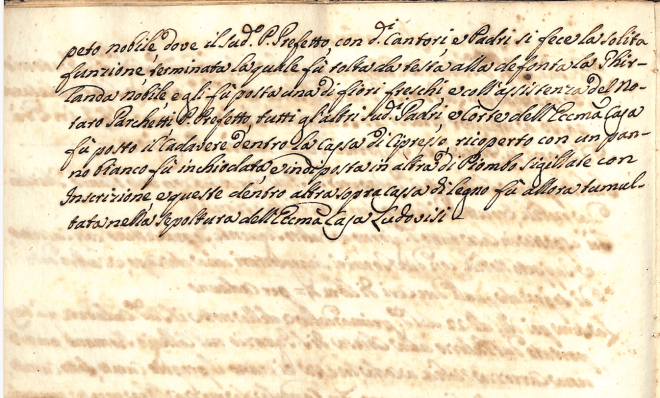

Afterward, the noble garland was removed from the head of the deceased and replaced with one of fresh flowers, and with the presence of the notary [Francesco] Parchetti, the Prefect Father, all the other aforementioned Fathers, and the court of the Most Excellent House, the body was placed inside a cypresswood coffin, covered with a white cloth, nailed shut, and then placed inside another lead coffin, sealed with an inscription, and these enclosed within another outer wooden box, and it was then entombed in the burial vault [in S Ignazio] of the Most Excellent House of Ludovisi.

About the author: Sarah Freeman in September 2025 enters the first-year class of the University of Pennsylvania, where she plans to study Classics. She is a 2025 graduate of the Morristown Beard School in Morristown, New Jersey. During the summer of 2024, she participated in the internship program at the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi. Sarah wrote then and reiterates now that she “had an amazing time uncovering more about the life of Princess Giacinta Orsini Boncompagni Ludovisi through my research. I am extremely grateful to HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for extending the amazing opportunity to work with primary documents in her archive, and to Dr. T. Corey Brennan at Rutgers University–New Brunswick for his endless guidance throughout the process, and for translating the transcriptions. I also give thanks to Nicole Freeto from the Morristown Beard School for inspiring me to study the rich history of Italy and Greece. I am honored to have worked on such a monumental project.”

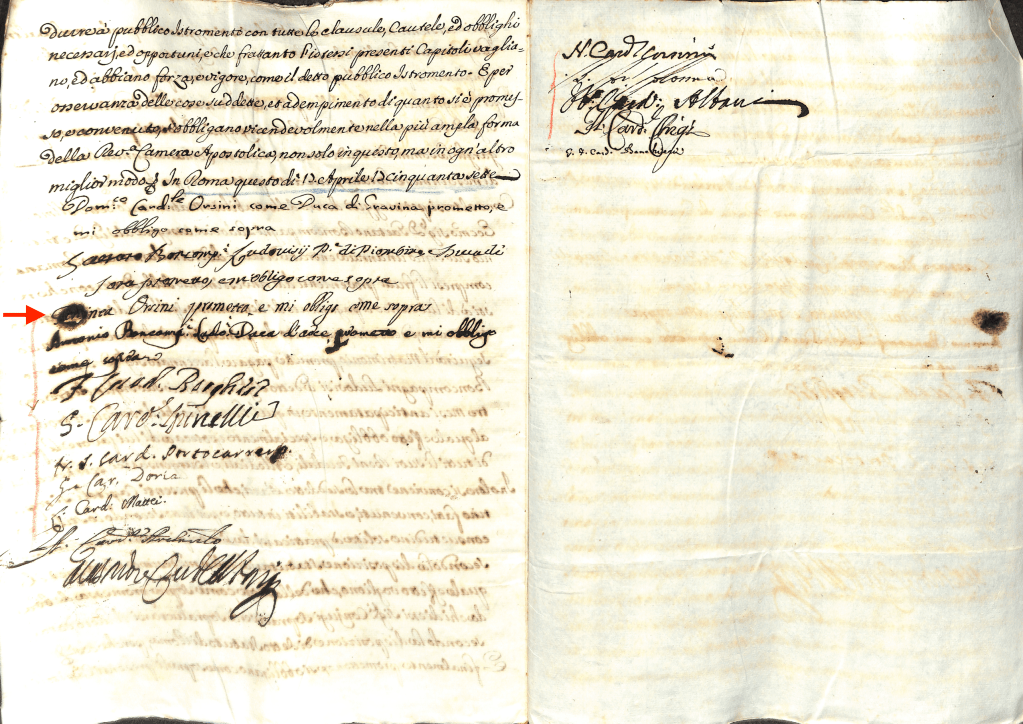

Signatories to marriage contract (17 April 1757) of Antonio (II) Boncompagni Ludovisi and Giacinta Orsini, signed by 13 Cardinals, one of whom is the father of the bride, Domenico Orsini, Duke of Gravina. Giacinta’s promise, written in her own hand, is indicated with the arrow. Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 592 no. 32; courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome

Leave a comment