Left: Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), detail of portrait of Philip IV of Spain (1656). Credit: National Gallery, London / Wikimedia Commons. Right: detail of portrait by unknown artist of Niccolò Ludovisi in Casino dell’Aurora, Rome. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi.

By Elif Cam (Princeton High School ’26)

Here I continue Part I of this post, in which I described and translated a previously unpublished 15-page letter that King Philip IV of Spain (reigned 1621-1665) wrote at Madrid on 24 August 1660 to the Prince of Piombino, Niccolò Ludovisi (1613-1664). The Spanish king had appointed Niccolò as Captain General of Aragon in 1659, and its Viceroy in 1660.

The letter is a lengthy directive on the management of fortifications on Spain’s Pyrenees border with France following the conclusion of the Franco-Spanish War (1635-1659). In this part, I analyze Philip’s letter in greater detail, discussing some of the principal events referenced, as well as five select aspects of the many issues that arise in this document: post-war border control, meritocracy in the Spanish army, restrictions on conscriptions of Aragonese locals, the provisioning of food for the military forces, and the scope of the legal powers of the Captain General in Aragon. I conclude with another unpublished document bearing on the career of Niccolò Ludovisi, Philip IV’s 1657 letter to the Prince informing him of his induction into the Order of the Golden Fleece. Sources for my discussion can be found at the end of this post.

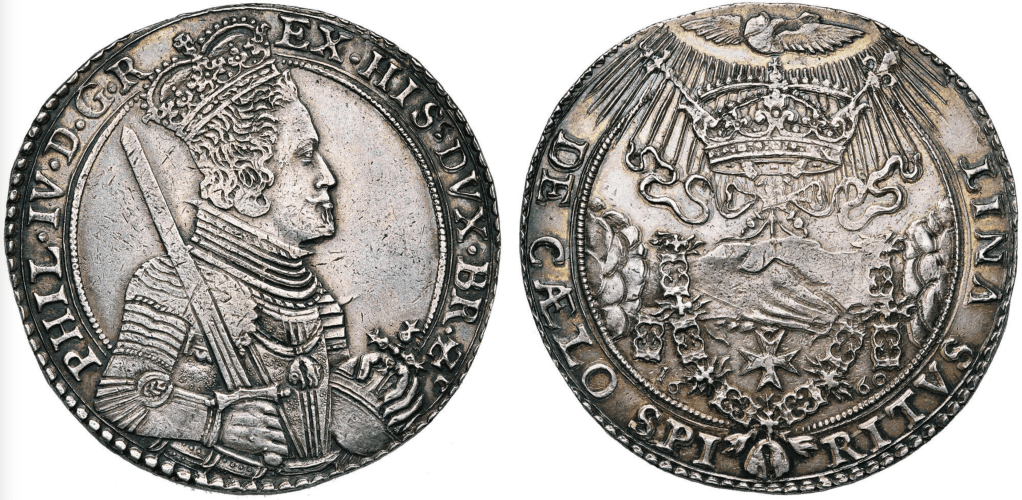

Silver medal, undated (1660), Antwerp (?), commemorating the Peace of the Pyrenees between Spain and France. Obverse: Crowned bust of Philip IV. Reverse: legend DE CAELO SPIRITVS VNIT (“the Spirit unites from Heaven”); beneath the dove of the Holy Spirit, two clasped hands, from which hangs the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Credit: Jean Elsen & ses Fils

King Philip IV begins the 1660 letter (page 1) by recounting to Niccolò the unrest against the Inquisition in the Kingdom of Aragon, expressly mentioning the dates 24 May and 24 September 1591, as well as an incursion through the mountains of Jaca in 1592. It comes as a surprise to see the king start by citing precedents from several generations previous; it seems important to understand why he thought this historical introduction was relevant.

The events of 1591—also known as the Alterations of Aragon or the Aragonese Rebellion of 1591—were riots against the Spanish Inquisition and its supporters. The unrest stemmed from around a century of tension resulting from the Spanish Crown’s attempts to exercise control over Aragon, especially through the Inquisition.

Spain (Seville mint, undated), Double Excellente, Ferdinand and Isabella (reigned 1479-1504). Obverse legend: FERNANDVS ET ELISABET. Reverse legend: SVB VMBRA ALARVM T(uarum) (“under the shadow of your wings”). Credit: Spink

The union of the Crown of Aragon and the Crown of Castile had effectively came about in 1479 with the accession of Ferdinand II to the throne of Aragon, who had married Isabella I of Castile ten years earlier, and ruled over Castile with her since 1475. Though Castile and Aragon were legally separate—and would remain so until 1716—Ferdinand and Isabella were the first to be regarded as king and queen of a dynastically unified Spain.

It was also in 1479 that the Spanish Inquisition was established in Aragon. Although that Kingdom had previously had an Inquisition in the Medieval era, this new institution differed significantly, as the royalty of Aragon had very little control over it (Haliczer, 2018). Bishops held power to suppress heresy and heretics in their courts, and inquisitors were appointed directly by the Pope. Indeed, a landmark papal bull of 1478 issued by Sixtus IV della Rovere gave Castilian sovereigns full power to name inquisitors who would have the same powers and jurisdiction as the bishops and papal inquisitors. King Ferdinand started to use the Castilian-based Inquisition to exert significant control over the Kingdom of Aragon. This led the new institution to be met with violent resistance in Aragon, particularly in the city of Teruel, leading Ferdinand to enforce power through threats of armed action (Haliczer, 2018).

Lorenzo Vallés (1830-1910), Death of Juan de Escobedo (ca. 1879). The painting shows the moment before the statesman’s assassination in the Callejón de la Almudena in Madrid on 31 March 1578. Credit: Museo del Prado

This tension between the Kingdom of Aragon and the Spanish crown over the Inquisition continued all through the sixteenth century, reaching a high point in 1590. In that year Antonio Pérez—former secretary to Philip II (king of Spain 1556-1598), who had been accused of the murder of Juan de Escobedo (1530-1578) and of conspiring against the king—fled from his Castilian prison and came to Aragon in hope of legal protection (Pérez, 2006). Philip II, realizing his former secretary would not be condemned by the Aragonese courts of justice, resorted to the Inquisition, the only institution whose power could prevail over the guarantees granted by the Aragonese laws.

Pérez was accused of heresy and handed over to the Holy Office, but was returned to the jurisdiction of the Aragonese Chief of Justice after a major riot against the Inquisition broke out on 24 May 1591. During the period from May to September of 1591, more members of the lower strata of the Aragonese society became deeply involved in the rebellion, and the insurrection became increasingly more radical (Pérez, 2006).

On 24 September 1591, some Aragonese nobles, fearing the growing social unrest and the reaction of the Spanish monarchy, attempted to transfer Pérez back to the Holy Office of the Inquisition. This attempt to turn the prisoner in terminated with a second riot, which was much more violent than the first one and resulted in over a dozen casualties., leading Philip II to conduct a military occupation of Aragon that continued until September of 1593. After the initial rebellions, Antonio Pérez and some of his Aragonese supporters escaped to France, where they worked with Catherine of Bourbon— the sister of Henry IV (king of France 1589-1610)—to plan a military expedition across the Pyrenees into Aragon to rouse the Aragonese to revolt against Spanish military occupation (Pérez, 2004). Called “Jornada de los bearneses”, or the Béarnese expedition, this is the 1592 incursion King Philip IV refers to in his letter.

So Philip IV cited these past incursions in Aragon and specifically the attack on the Pyrenees border to show Niccolò the need for rigorous maintenance of the garrisons in this region, despite the recent conclusion of a long war with France. The king here also prepares for a major theme of this letter, his emphasis on ensuring good civil/military relations in the area.

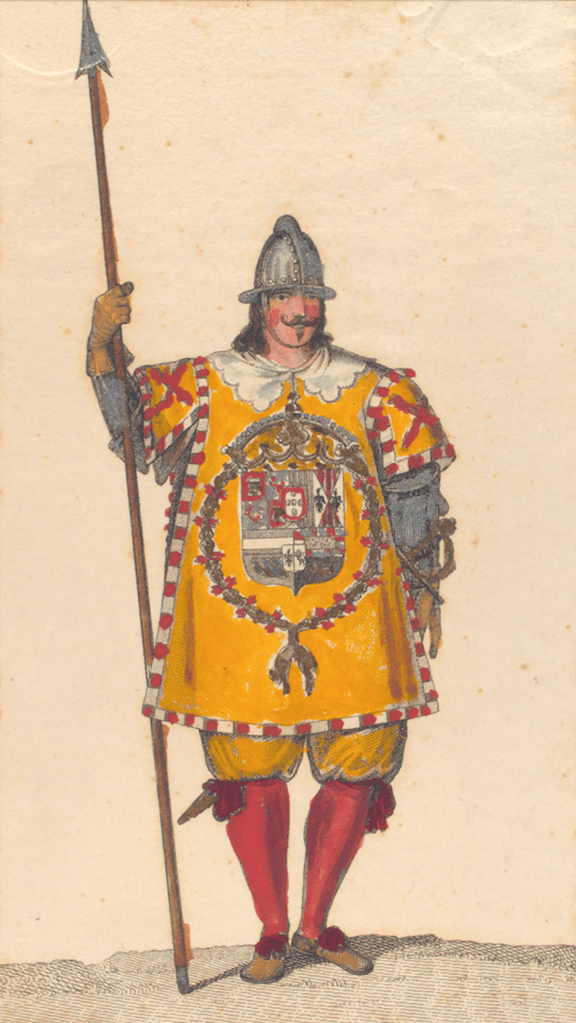

Piquero; Mosquetero. Regimiento de Guardias de infanteria de Felipe IV. Casa real (1660) = Pikeman; Musketeer. Regiment of Infantry Guards of Philip IV. Royal Household. Credit: The Vinkhuijzen collection of military uniforms, New York Public Library.

Next in his directive (still on page 1), Philip IV transitions to the management of the army. He emphasizes the importance of meritocracy, saying that among those seeking posts, “the most deserving and reputable shall be appointed and from there promoted to captains in the next elections. Others of equal merit shall replace them, ensuring continued and reliable tower defense.”

Spain’s large and fragmented military needed professional management, and so king Philip IV promoted meritocracy in his armies to ensure efficiency over simply giving positions to nobility (Picouet 184). In the 1500s, a rigorous system of training and promoting officers had been devised to help maintain the authority of the Spanish kings in the armed forces throughout the empire. A person in the army would start from low ranks as a soldier, and move onto sergeant, ensign (alférez), and captain after a minimum 10 years of service. If they performed well, they could even be nominated to Maestro de Campo (Picouet 183).

To further ensure professionalism, Philip in his letter (page 5) requests that no natives of Aragon be appointed to garrisons, even though he has “complete confidence in their loyalty”. He explains that “when native soldiers are allowed, they often hold additional jobs and are content with half or a third of the standard pay, allowing the captains to retain the rest in exchange for letting them pursue their occupations” and that “all the kings of Spain have maintained this same rule”.

This meant that Niccolò Ludovisi would need to look elsewhere to enlist soldiers, and recruitment would likely not be easy. In the 1630s, to fill the quota of new recruits for Spain’s armies, local authorities and city councils enlisted all men considered as useless for their communities, even if it was against their will (Picouet 191). This compulsory recruitment system had to be repeated year after year in the 1640s-1650s, leading many recruits to desert and the system to become very unpopular in Spanish society (Picouet 191). In the early 1660s, the unpopularity of recruitment would be something Niccolò Ludovisi would have to deal with as he tried to man his garrisons, especially following the end of the Franco-Spanish War in 1659, since soldiers no longer had an immediate reason to serve.

Guardia de los archeros de la cuchilla; Guardia española (1660) = Guard of the Halberd Archers; Spanish Guard. Credit: The Vinkhuijzen collection of military uniforms, New York Public Library

In discussing the management of the garrisons, Philip IV writes about obtaining and renewing food supplies, saying (page 4) that “for the bread that is generally presumed to be provided to the soldiers, it has seemed better, if it can be avoided, that they buy it themselves, receiving five escudos in coin (at ten reales per escudo) as part of their pay. You will determine in which locations this can be done and where it would be suitable, to keep the troops satisfied, and you will inform me.”

Historically, since the administration of the Spanish empire could not provide the enormous quantity of supply needed by the armies, a system of using private suppliers was established by the end of the 1500s, and later introduced to all Spanish troops (Picouet 195). Local military authorities would sign a contract with a victualler to deliver “ammunition bread” to all army personnel. The contract established the price of bread by pounds; there the military authorities stipulated how much would be delivered and to where.

For the victuallers, profit depended on the price of bread: the figure frequently fluctuated, likely leading them to raise prices. While this kind of bulk purchasing system surely made the distribution of the bread easier, it was likely costly—ammunition bread made up 25.8% of the army’s spending in 1663 (Picouet 195). That could be the main reason why Philip advises giving individual soldiers a bread stipend with which they can buy the bread themselves rather than paying private suppliers. Soldiers purchasing their own bread from independent sources also likely increased the quality of the bread, by creating almost a free market rather than buying bulk from a sole supplier. Soldiers could go for the best they could get with the money they received, ensuring competition among sellers.

Piquero Regimento de Guardias del Rey Felipe IV. Casa real (1661) = Pikeman, Regiment of Guards of King Philip IV. Royal Household. Credit: The Vinkhuijzen collection of military uniforms, New York Public Library.

Finally, questions of jurisdiction. At the time of the reign of Philip IV, the defense of the Spanish land in the Iberian peninsula was divided into various territories, or “General Captaincies”, each with a direct representative of the king called the Captain General and/or viceroy (Picouet 122). This Captain General was in command of all the military structures in their certain territory, as well as in charge of the general governance of the area.

In his letter to Niccolò Ludovisi in his capacity as the Captain General of the Kingdom of Aragon, King Philip IV outlines various historical disputes in the Kingdom of Aragon relating to the authority of that military office. He writes (page 7) that “I ordered a decree to be issued to the Marquis of Aytona”, who also served as Captain General of Aragon, which clarifies the matter. The long decree (pages 7-10) the king cites however dates to 1611, and was issued rather by his father Philip III, who reigned 1598-1621, to Miguel de Moncada y de Moncada (1558–1626), the 3rd Marquis of Aytona. By 1660, there had been three additional Marquises of Aytona; we shall meet the 6th Marquis below.

In the decree of 1611, Philip III told the 3rd Marquis of Aytona that, as Captain General, he shall have jurisdiction over all crimes committed by the military and over any related civil or criminal causes involving military personnel —but not to others. Henceforth (page 9) “soldiers who commit excesses must be punished strictly by the Captain General, without being able to claim the privilege of manifestación or any other immunity”. Here manifestación refers to the Aragonese privilege of legal protection against arbitrary detention, a right akin to habeas corpus.

Evidently there had been disputes about the extent of a Captain General’s jurisdiction. Philip III notes (page 8) that when the Duke of Alburquerque held that post in 1593—the reference is to Beltrán III de la Cueva y Castilla (ca. 1550–1612)—it was argued that the Captain General could not exercise jurisdiction except in times of war or serious disorder according to Aragonese laws. Even if individuals involved in the case were in the military, the king continues, it was difficult during peacetime to prosecute crimes or cases over which the Captain General had jurisdiction. Since local laws restricted his power to military matters alone, matters concerning others were claimed to remain with the civil judges.

Guardia española, Casa real; Guardia alemana Casa real; Guardia de los archeros de la cuchilla en traje de guerra (1660). Credit: The Vinkhuijzen collection of military uniforms, New York Public Library.

Military justice in the Spanish Empire depended on two juridical instances. At the high level, a Maestro de Campo General was supported by an Auditor General to deliver justice on cases concerned with crimes against the army or affairs between soldiers of different units. At a lower level, military justice was applied by the Maestro de Campo of the tercio (= a Spanish infantry formation of the 16th and 17th centuries) with cases being brought to the higher level if officers, captains, or noblemen were involved. The military legal framework was called “military privilege” indicating that a soldier could only be judged by a military tribunal (Picouet 198). This meant that when civilians and soldiers were both involved, there would be a compromise between two legal jurisdictions. But sentences against soldiers could be decided by military jurisdiction (Picouet 199).

So Philip IV in citing his father’s 1611 letter tries to clarify the matter of military jurisdiction for Prince Niccolò, giving also the context of debates that occurred in the past in the Kingdom of Aragon. The reason why the king treats the matter at such length is that Niccolò will be a Captain General during peacetime and his jurisdiction might be disputed.

Silver French écu (1647) minted under Louis XIV commemorating the capture of Porto Longone on the island of Elba. Obverse: legend NIL NISI CONSILIO (“nothing without planning”) surrounding crowned shield of France encircled by the double collar of the Orders of Saint Michael and of the Holy Spirit. Reverse: legend NON HAEC SINE NUMINE DIVUM (“nor these events without the divine power of the gods”), surrounding a fleet of nine ships that attacks an island inscribed ILVA (Elba). Credit: iNumis

An epilogue. Niccolò Ludovisi had a long history with the Spanish Crown, which had confirmed him as Prince of Piombino (after a massive payment in cash and kind) in 1634. The Prince sent troops at his own expense to help Spain when the French launched a (successful) naval expedition against Porto Longone on Elba in June 1646. He also supported the Spanish response to the Neapolitan ‘Masaniello’ revolution of July 1647, by offering financial and military aid to Philip IV’s son, the 18 year old Don John of Austria, sent to restore order in the city. Niccolò remained loyal despite French attempts to draw him away from the Spanish faction in Rome (Brunelli, 2006).

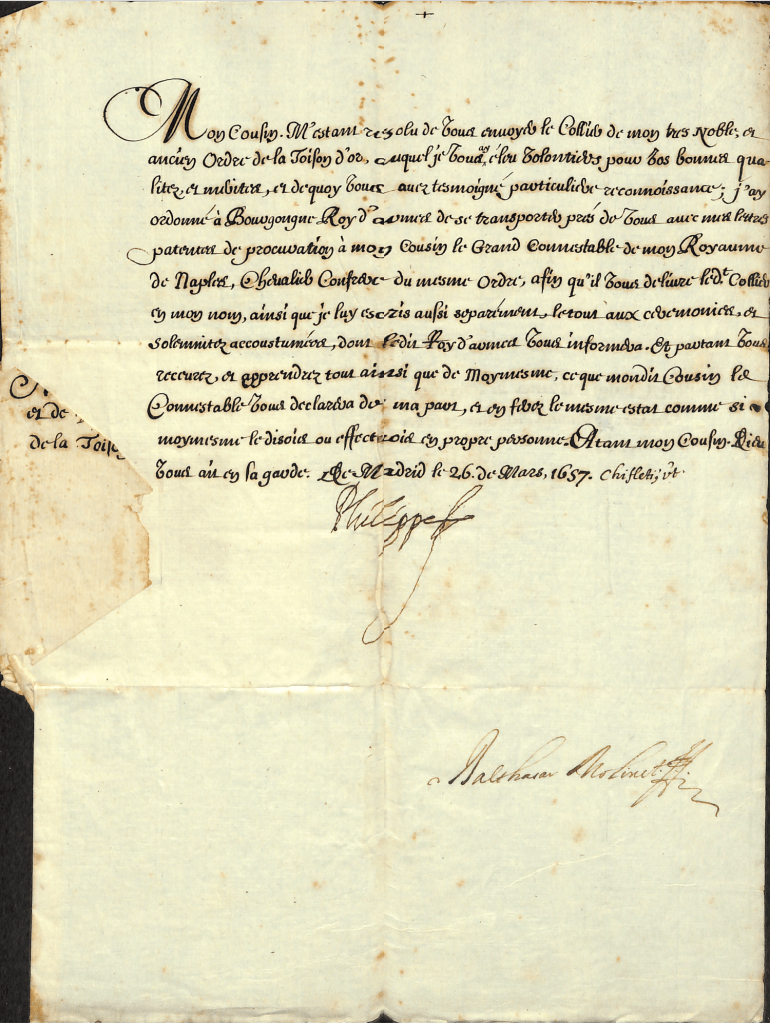

For his longtime loyalty to the Spanish empire, on 26 March 1657, Philip IV provided that Niccolò Ludovisi be inducted into the Order of the Golden Fleece. This was a Roman Catholic order of chivalry dating back to 1430, and was counted as one of the highest honors the Spanish monarch could bestow. Niccolò was the first member of the Ludovisi (or equally pro-Spain Boncompagni) family to receive this honor. Only four were inducted in all: Niccolò Ludovisi (in 1657) and his son Giambattista Ludovisi (1670) as Princes of Piombino; Antonio Boncompagni (1702) as Duke of Sora (for his ceremonuy of induction see here), and his son Gaetano Boncompagni Ludovisi (1736) as Prince of Piombino.

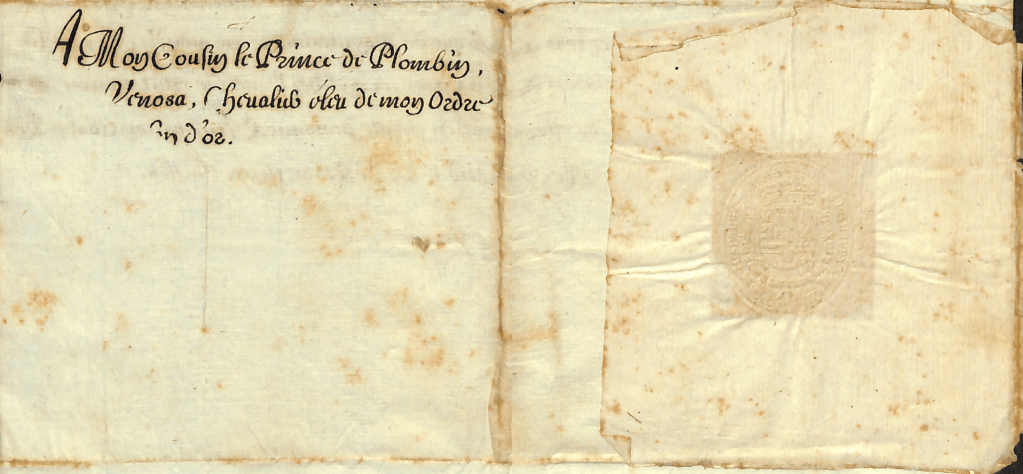

Though the fact of Niccolò’s induction into the Order is perfectly known, the document (written in French, reflecting the honor’s Burgundian roots), found in the private Boncompagni Ludovisi archive in the Casino dell’Aurora, is unpublished. The king’s letter reveals an important point: that Niccolò received the Golden Fleece collar not in Madrid but in Naples, from the then-acting Gran Conestable of that city, Guillén Ramón de Moncada y Moncada (d. 1670), 6th Marquis of Aytona, a major Spanish nobleman and statesman. The head of the house of Moncada, he had served as Viceroy of Sardinia (1644–1649), Viceroy of Valencia (1652–1656), and remained influential in Madrid as a counselor of Philip IV. Below is an image of the letter and its translation:

Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 4 no. 8, letter (26 March 1657) of Philip IV of Spain to Niccolò Ludovisi, informing him of his grant of the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

“My Cousin [a traditional formal greeting among European sovereigns], Having resolved to send you the Collar of my most noble and ancient Order of the Golden Fleece, to which I very willingly admit you on account of your good qualities and merits—of which you have shown particular understanding—I have ordered the King of Arms of Burgundy to travel to you with my letters patent of procuration to my cousin the Grand Constable of my Kingdom of Naples, Heraldic Counselor of the same Order, so that he may deliver to you the said Collar in my name, as is prescribed to him separately, according to the customary ceremonies and solemnities, of which the said King of Arms will inform you. Therefore, you shall receive and accept all as if it came from myself, what my said cousin the Constable shall declare to you on my behalf, and you shall believe and regard it as though I myself were saying or doing it in person.

With that, my Cousin, may God keep you in His care.

Written at Madrid, the 26th of March, 1657.”

Golden Fleece chain (15th century) by Bruges goldsmith and jeweler Jean Peutin, one of 24 he created for the first Knights of the Order. Credit: Artstor Collections

Sources:

Brunelli, Giampiero. “LUDOVISI, Niccolò.” Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 66, Treccani, 2006.

Haliczer, Stephen. Inquisition and Society in the Kingdom of Valencia, 1478-1834. University of California Press, 2018.

Picouet, Pierre. The Armies of Philip IV of Spain 1621-1665: The Fight for European Supremacy. Helion, 2019.

Pérez, Jesús Gascón. “La «Jornada De Los Bearneses», Epílogo De La Resistencia Aragonesa Contra Felipe II.” Bulletin Hispanique, [Vol. 106], N.º 2 (2004), pp. 471-496.

Pérez, Jesús Gascón. “The Aragonese Rebellion of 1591.” In Immanuel Ness (ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest. 1500 to the Present, Oxford, Blackwell, 2006.

Elif Cam is a rising senior at Princeton High School participating in the internship program at the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi. She is interested in environmental policy, history, and composing music. She is extremely grateful for the guidance of Dr. T. Corey Brennan, for getting the opportunity to work with fascinating and previously unpublished sources in the archive generously shared by HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, and for being able to get to know King Philip IV and Niccolò Ludovisi over this journey!

Verso of Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 4 no. 8, letter (26 March 1657) of Philip IV of Spain to Niccolò Ludovisi, informing him of his grant of the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Credit: HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Leave a comment