Spring 1914: Aliotti and other Italian officials in Durrës, Albania. Published in L’Illustrazione Italiana 19 April 1914 (no. 16) p379. Courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi

By Maria Walsh (Rutgers ’27)

As its readers know, the Boncompagni Ludovisi archive in Rome’s Casino dell’Aurora has provided scholars with a vast wealth of historical primary sources, spanning centuries and showcasing an impressive array of historical figures and subjects. However, it was a great surprise to uncover an entire trove of documents on the early 20th century Italian ambassador, Baron Carlo Alberto Aliotti (1870-1923), who, among many other exploits, handled conflicts in the highly contested region of Albania in the years leading up to World War I.

The recently uncovered Boncompagni Ludovisi dossier on Baron Aliotti provides a glimpse into his prolific and fascinating career, containing letters, telegrams, photographs, and certificates from the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I would like to note that I have been able to access and research these documents due to the courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi. Baron Aliotti was the maternal grandfather of Princess Rita’s late husband, HSH Prince Nicolò Boncompagni Ludovisi (1941-2018), which explains the presence of his papers in the Casino dell’Aurora.

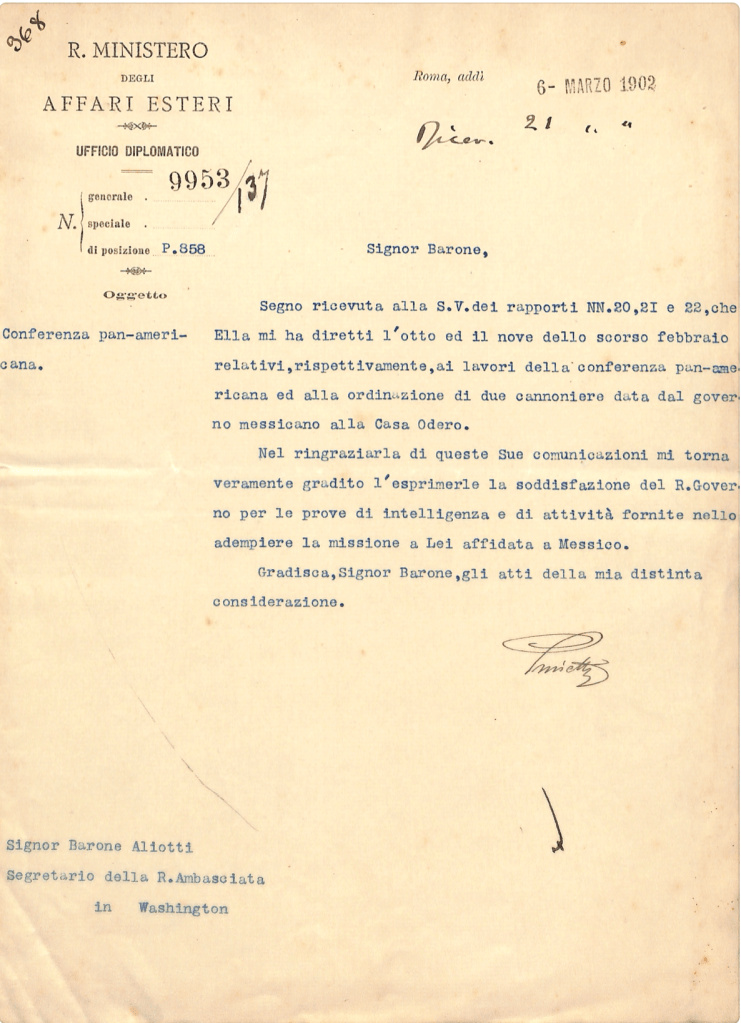

Letter (6 March 1902) to Aliotti, then based in Washington DC, from Giulio Prinetti (1851-1908), Italian Foreign Minister 1901-1903. In 1939 Aliotti’s daughter Bonacossa (1908-1995) would marry Prinetti’s grandson Gregorio Boncompagni Ludovisi (1910-1988), and soon be parents of HSH Prince Nicolò Boncompagni Ludovisi (1941-2018). Courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi.

Until recently, there has been limited biographical and scholarly information on the figure of Baron Aliotti, perhaps due to the confidentiality of his work as a diplomat. The main account of this man’s career dates to 1960, in the Treccani encyclopedia article of Giovanni Tantillo. However, my current research into the dossier on Aliotti has begun to paint a clearer picture of the ambassador as a highly determined, strong-willed, and skilled individual. This letter captures an intense moment in his career that highlights these qualities: the Albanian crisis beginning in 1914.

Durrës (May or June 1914): Albanian soldiers and civilians hauling artillery. Credit: Marquis di S Giuliano Photo Collection

Baron Carlo Alberto Aliotti was born into a noble family in Smyrna in 1870, now Izmir in modern-day Türkiye. His noble birth aided his advancement into the consular service in 1893, along with his alleged status as a Freemason. The Aliotti family also had a history of diplomatic service: Aliotti’s father, Baron Antonio Aliotti (1814-1889), served as consul general of Tuscany to the city of Smyrna. After completing several assignments in Constantinople, Salonika, and Vienna, Aliotti entered the diplomatic career in 1896. His first significant role was that of chargé d’affaires in Caracas, Venezuela in 1903; he was then sent to Mexico City in 1912 as minister plenipotentiary.

One of the most notable moments in Aliotti’s career was his role in the Albanian crisis, beginning in February 1914, as extraordinary envoy and minister plenipotentiary in the city of Durrës (ancient Dyrrachium). His objectives were to support the government of the Prince Wilhelm of Wied (crowned Prince of Albania 21 February 1914) and maintain Italian influence in a region coveted by various European nations such as Montenegro, Serbia, Greece, and Bulgaria. Despite the Albanian mission ultimately culminating in failure, archival evidence reveals Aliotti as ambitious, shrewd, and dedicated in his duties.

Durrës 1914: Baron Aliotti with Italian military officers and troops. Courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi.

While he garnered considerable support from Italy and the press, Aliotti’s policy in Albania was largely unpopular, unsuccessful, and faced criticism from ambassadors from the other nations in the Triple Alliance, Germany and Austria-Hungary. Giovanni Tantillo’s Treccani article, our main biographical source on Aliotti, claims that Aliotti withdrew from Albania in December of 1914, having allegedly spent less than a year in the region. However, the date on the telegram shows that Aliotti was still in Albania in late 1915.

Afterwards, Aliotti was appointed minister plenipotentiary to China in 1916 and then commissioner to Sofia. He later returned to Albania in June 1920 to acknowledge its new government (under the de facto leadership of Sulejman Delvina), ensure the withdrawal of Italian troops, and obtain permission for an Italian naval base on Sazan Island, another mission that did not end successfully. In November 1920, he was sent as an ambassador to Tokyo as the head of the Italian mission.

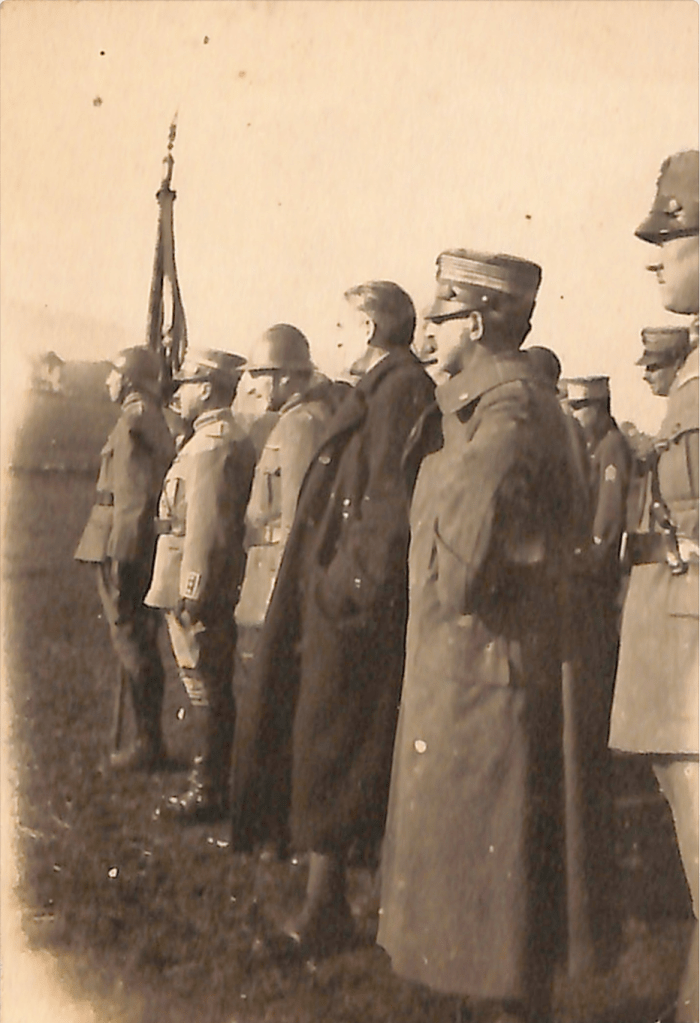

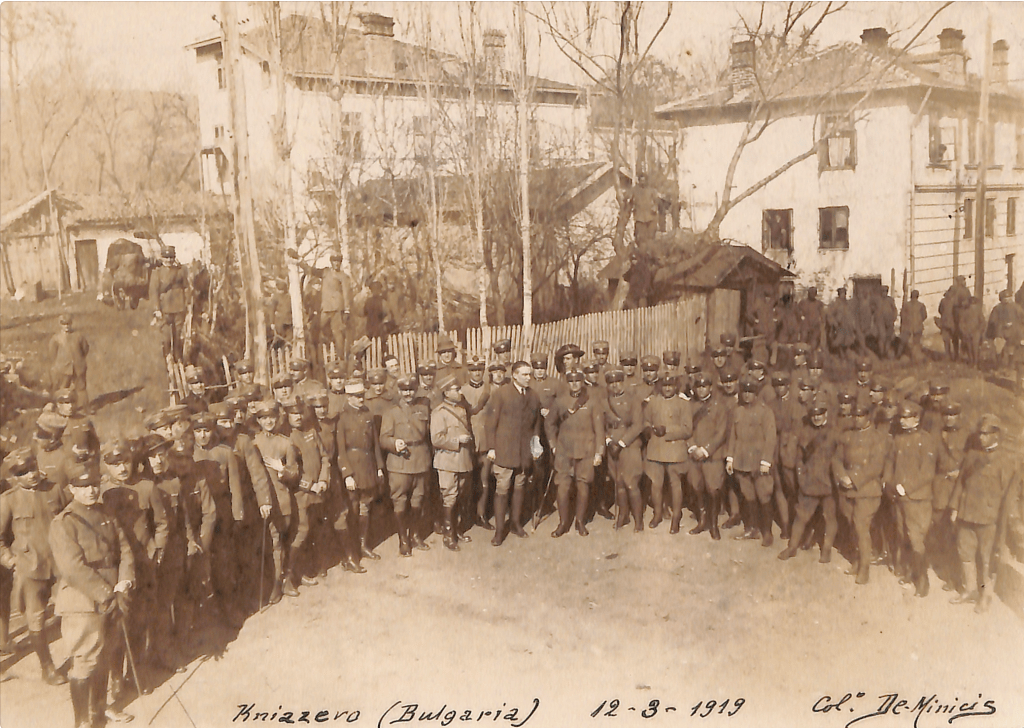

Baron Aliotti (center, in civilian dress) with Italian officers 12 March 1919, in (apparently) Knyazhevo, a neighborhood at the SW edge of Sofia. Courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi

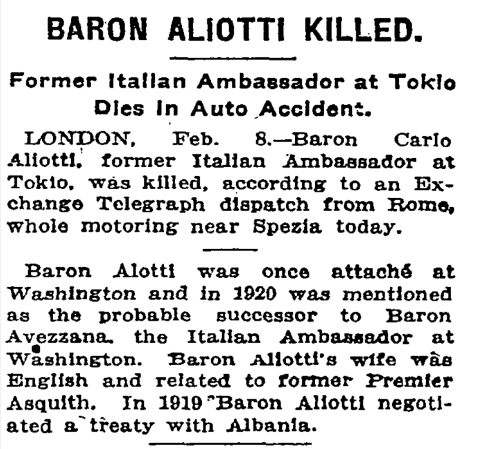

Aliotti was fired from his position in Tokyo by the newly appointed Italian prime minister and leader of the Fascist party, Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), in November 1922. Shortly afterward, on 8 February 1923, he perished suddenly in an automobile accident in Italy near La Spezia. It is hard not to suspect that Mussolini was somehow involved, as the prime minister was working at the time on removing political opposition and dismantling democracy as he sought to appoint himself dictator. Additional research into the final years of Aliotti’s career, specifically during his role as minister to Tokyo, may further illuminate his political position at the time and clarify if he may have been a target of Mussolini and his Fascist party.

New York Times 9 February 1923 p15. Aliotti was married in early 1908 to Esther Florence (Fiorenza) Vignoles (London 1870-Rome 1944); their sole child, Bonacossa, was born 12 December 1908.

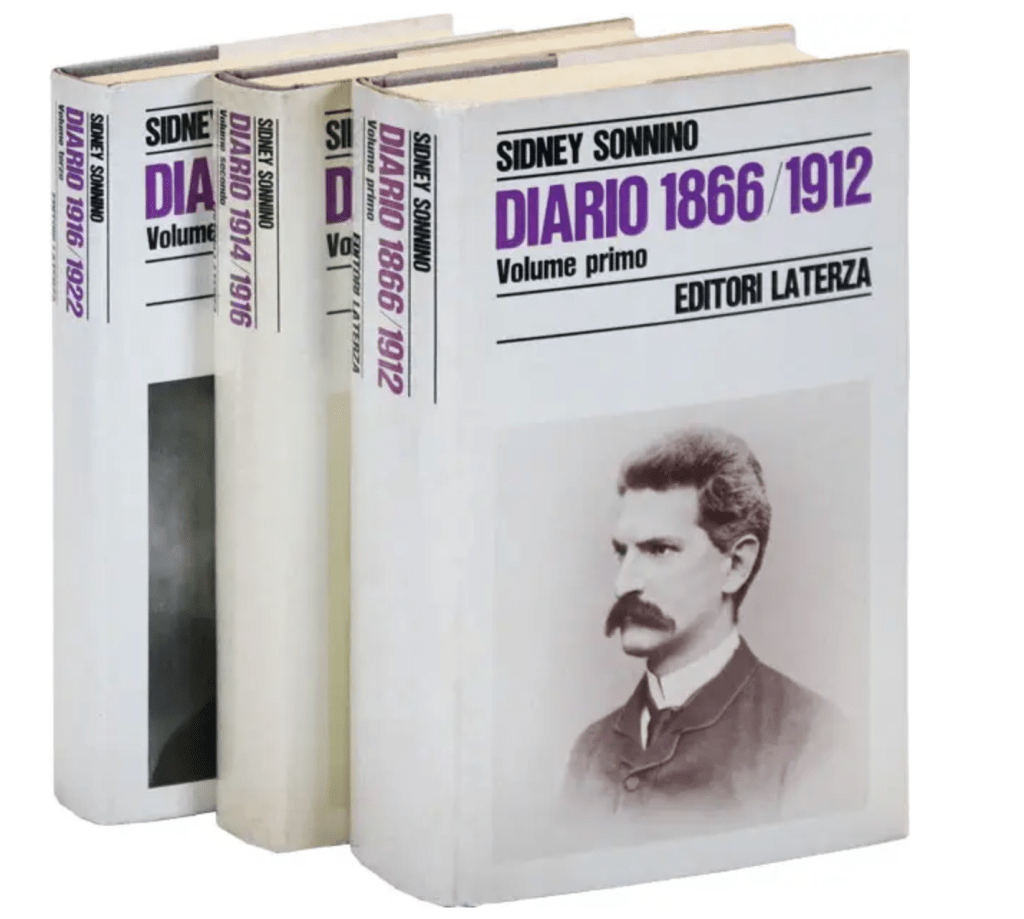

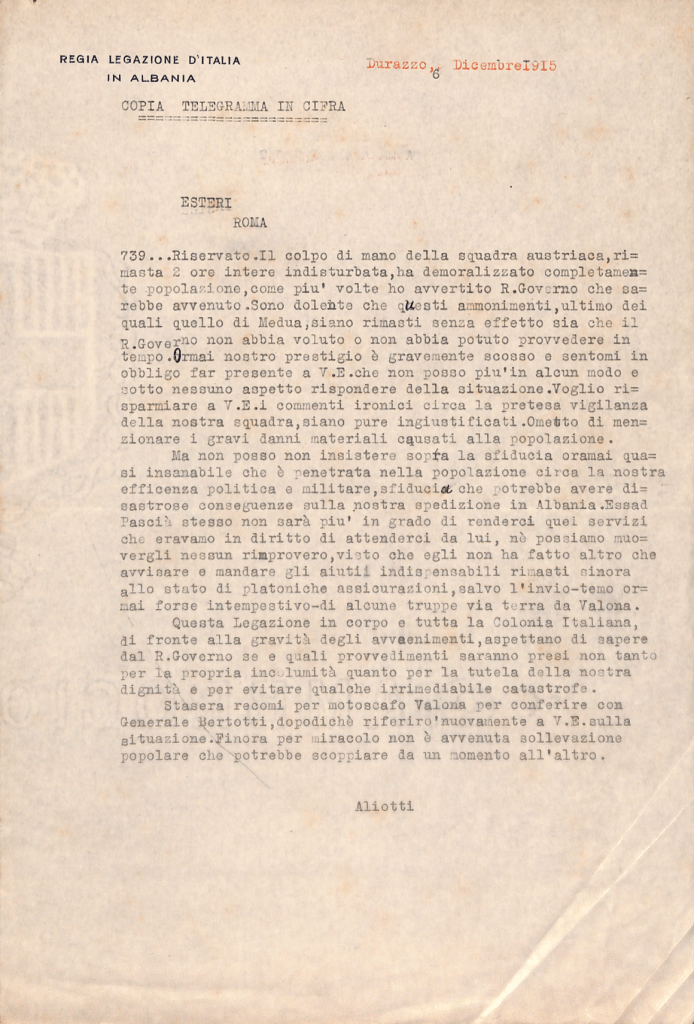

The following letter, from the Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi in the Casino dell’Aurora, is the official transcription of an encrypted telegram from Baron Aliotti to the Minister of Foreign Affairs in Italy, Sidney Costantino, Baron Sonnino (1847-1922), addressing the surprise attack on Italian troops by an Austrian squadron and the failing Italian military situation in Albania.

Publication, edited by Benjamin F. Brown in three volumes, of Sidney Sonnino’s Diary, 1912-1922 (Bari: Editori Laterza, 1972). Sonnino (1847-1922) twice served as Italy’s Prime Minister (1906; 1909-1910), and was the Italian minister of Foreign Affairs during WW I.

The concise, blunt letter demonstrates Aliotti’s indignance and frustration at the situation, given his determination to secure Albania as a political asset for Italy. His approach to failure as a skilled diplomat is also on display in the telegram. The translation of the telegram is below.

Courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi.

ROYAL ITALIAN LEGATION IN ALBANIA

Durrës, 6 December 1915

COPY OF ENCRYPTED TELEGRAM

FOREIGN AFFAIRS, ROME. 739… Confidential.

The surprise attack by the Austrian squadron, which remained for two full hours completely unopposed, has completely demoralized the population, just as I have warned the Royal Government would happen on multiple occasions. I regret that these warnings, the last of which concerned Medua, have been ignored, whether because the Royal Government was unwilling or unable to act in time.

By now our prestige has been severely damaged, and I feel obliged to inform Your Excellency that I can no longer be responsible for the situation in any way or under any aspect. I wish to spare Your Excellency the ironic comments circulating about the supposed vigilance of our fleet—even if they are unjustified. I will refrain from mentioning the serious material damages inflicted upon the population.

But I must insist on the now almost irreparable distrust that has taken root among the population regarding our political and military efficiency—a distrust that could have disastrous consequences for our expedition in Albania. Essad Pasha himself will no longer be able to provide us with those services we had a right to expect from him, nor can we reproach him, given that he has done nothing but issue warnings and send the indispensable help that has so far remained merely a platonic assurance, except for the dispatch—which I fear may now be too late—of a few troops overland from Valona.

This Legation as a whole and the entire Italian Colony, faced with the gravity of events, await word from the Royal Government on if and what measures will be taken, not so much for our own safety but to protect our dignity and to avoid some irremediable catastrophe.

Tonight I depart by motorboat for Valona to confer with General Bertotti, after which I will report again to Your Excellency on the situation. So far, by a miracle, a popular uprising has not occurred, but it could break out at any moment.

Aliotti

This telegram is noteworthy for a few reasons. It is situated almost directly in the middle of Baron Aliotti’s career, presumably at the height of his influence. It has been sent in code, noted by “in cifra” (“encrypted”), underlining the high tension of the situation in Albania and instability of the Italian mission. Regarding the main issue of the telegram, the surprise attack by the Austrian squadron, Aliotti takes no responsibility for the events that have occurred. Most importantly, it places Aliotti firmly in Albania in December 1915, a full year later than his own biographer in the Treccani encyclopedia claims he departed from the region.

Durrës, spring 1914: Captain Fortunato Castoldi (1876-1961) [l.], Admiral Eugenio Trifari (1860-1954) and Baron Carlo Aliotti (holding cane). Credit: Marquis di S Giuliano Photo Collection

It may be helpful to provide additional background on the political situation in Albania. For this, Isa Blumi provides a valuable summary in the International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Following the collapse of the Ottoman Balkans in 1912, there was a power vacuum in Albania, leading to a contest among European nations to assert dominance in the region. On 16 April 1915, there was a secret agreement between Italy, Great Britain, France, and Russia to divide up Albania, with a “Muslim” zone being controlled by Italy. Austria had already been controlling northern Albania since January 1915 and had designs for further expansion, ultimately seeking to remove all Italian influence and control an autonomous Albania. Aliotti, then, has the opposite goal: to defend Italian control against a threat that he seems to have already perceived.

Durrës (7 March 1914): the arrival of the Principality of Albania’s new sovereign, Prince Wilhelm of Wied (1876-1945, saluting). His effective reign lasted only until 3 September 1914. Credit: Marquis di S Giuliano Photo Collection

Aliotti’s tone in the telegram is decidedly frustrated, yet restrained, likely in order to show respect and deference to the Minister of Foreign Affairs—his superior. Aliotti would have reported directly to Baron Sonnino and, indirectly, king Victor Emmanuel III, who reigned over Italy at the time. The fact that the telegram is encrypted, as well as the edge in Aliotti’s words, suggest that Aliotti was of a high status and in close connection with his superiors, as he does not seem to fear speaking his mind. It seems very likely that there was conflict between Aliotti’s desires and ambitions for Italy and those of his superiors, given that his warnings about the Austrian attack were dismissed.

It is important to note that this is only one of many documents on Aliotti’s career, with much more to be uncovered. The Boncompagni Ludovisi dossier on his career is rich with first- and secondhand evidence from his diplomatic negotiations from all parts of his career. Aliotti’s career in Japan is especially of interest, given its proximity to his removal from the service and his untimely death at the age of 53. Further research into the dossier will continue to uncover more about this fascinating but understudied historical figure.

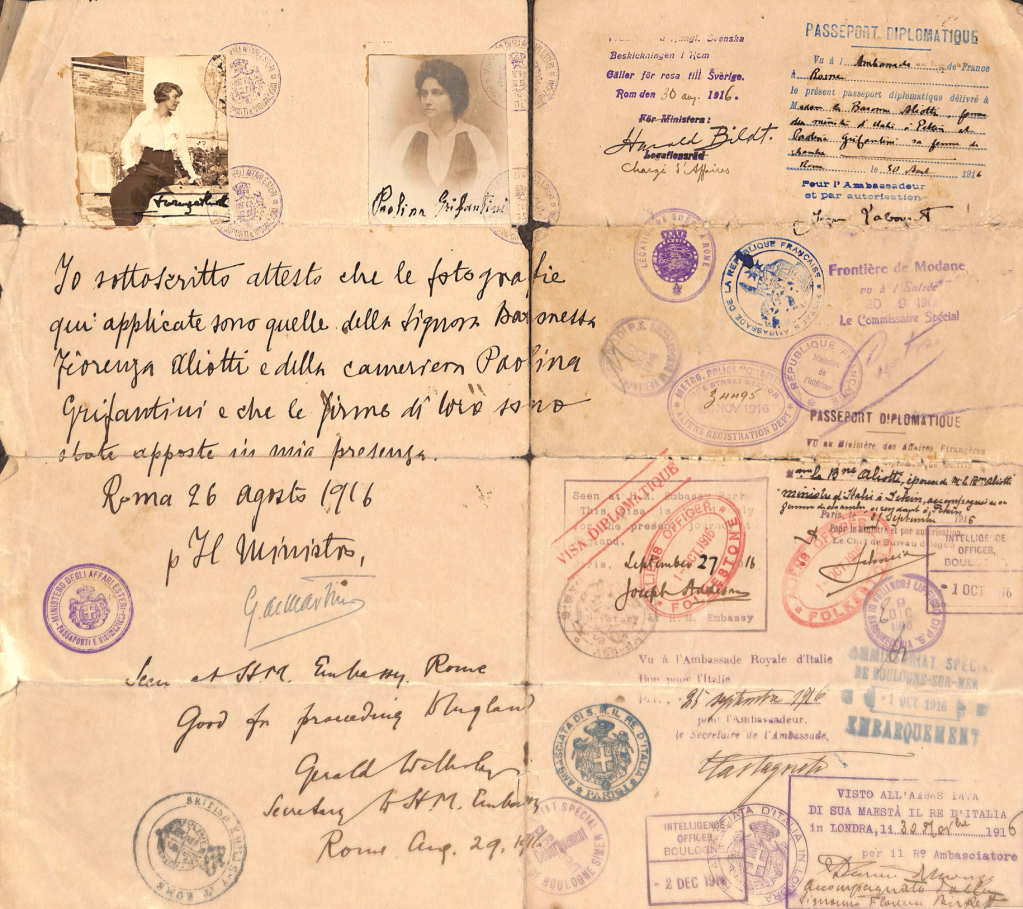

Diplomatic passport pages (1916) of Baroness Esther Florence (Fiorenza) Aliotti (née Vignoles), 1870-1944. After her husband’s death in an auto crash she competed as a race car driver, finishing second (of 14) in the 1932 Paris-Rome Rallye Feminin, in which she drove an Alfa Romeo. Courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi.

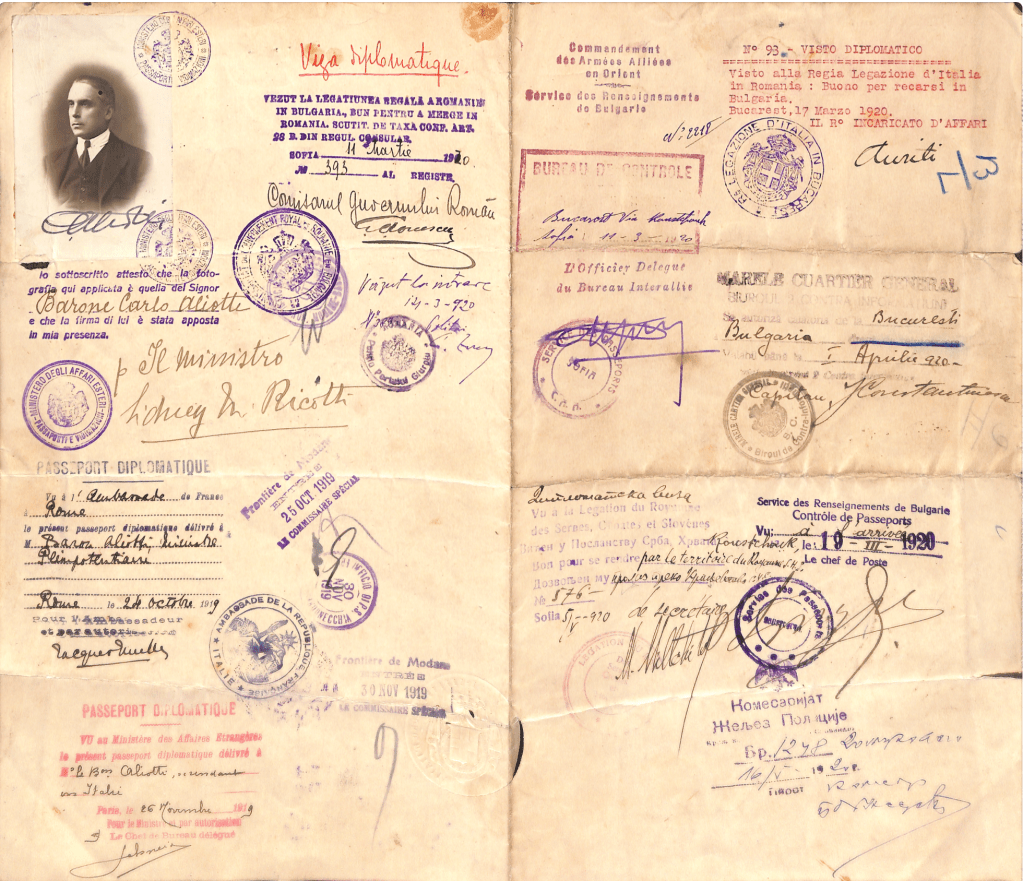

Diplomatic passport pages (1919-1920) of Baron Carlo Alberto Aliotti, 1870-1923. Courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi.

Maria Walsh is a junior in the School of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, majoring in Classics and studying Political Science and Arabic. She is a member of Zeta Epsilon, the Rutgers chapter of the Classics honor society, Eta Sigma Phi. Under the supervision of Dr. T. Corey Brennan at Rutgers University, she has been working on the Aliotti dossier for the past two semesters and is excited to finally publish her work on the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi. Maria is planning to study in Rome at the Intercollegiate Center for Classical Studies with Duke University during the Spring 2026 semester. She would like to thank Dr. Brennan for his continuous guidance and patience, as well as Dr. Bice Peruzzi at Rutgers University for her invaluable mentorship in Classics and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for providing the opportunity to engage in meaningful historical research.

Leave a comment