By Emilie Puja (Rutgers BA ’25, MI candidate ’27)

Most of the ancient inscriptions once owned by the Boncompagni Ludovisi family have been moved after the 1885 dissolution of Rome’s Villa Ludovisi and many lost, and there has never been an attempt to collect them. In 1880, Theodor Schreiber recorded 339 ancient works of art in a comprehensive catalogue of Villa Ludovisi antiquities, but just 14 of them have inscriptions. Thanks to modern technology (specifically online epigraphic databases), I have found 61 inscriptions in Latin and Greek that used to or still belong to the Boncompagni Ludovisi, for which we can identify item type, material, provenance and current location (especially important), and more.

All 61 inscriptions can now be found on Provenance Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi Online (PABLO), including their transcriptions, location history, provenance information, material, and more. Each item has a unique PABLO ID consisting of identification numbers assigned by the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL), Inscriptiones Graecae Urbis Romae (IGUR), Schreiber’s 1880 Die antiken Bildwerke der Villa Ludovisi in Rom, and/or B. Palma (ed.) Museo Nazionale Romano. Le sculture I.4-6 (1983-1986). Many also include images, with most being photographs and some being sketches from CIL. It is hoped that this database will aid with tracing and finding the many epigraphical texts in the Ludovisi collection that have disappeared.

Of thse inscriptions, 31 of these were observed at the Villa Ludovisi at some point. Initially, I was under the impression that the Ludovisi and Boncompagni Ludovisi did not collect inscriptions for their own sake, that they acquired ancient artwork which just so happened to have inscriptions. Schreiber’s catalogue certainly gives us this impression, as he only recorded inscriptions if they were on artworks. However, by working through CIL, I could identify inscriptions observed on Ludovisi property by a wider scope of authorities.

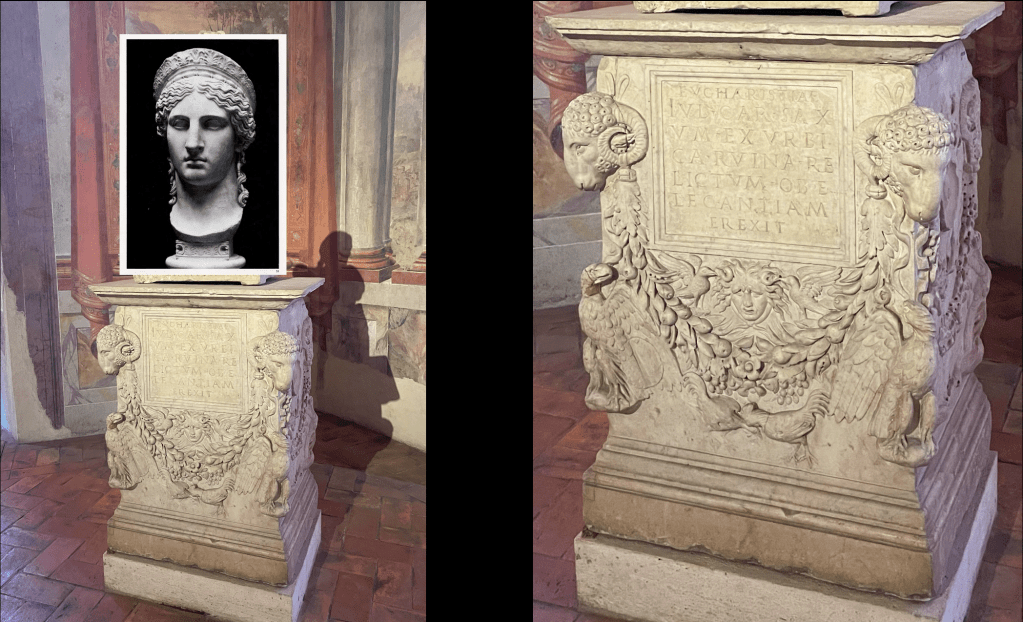

Above: my reconstruction of the placement of the Hera or Juno Ludovisi (Schreiber 104) on a Roman funerary monument (Schreiber 105) to which was added in the late 15th or early 16th century an inscription, probably in honor of Cardinal Giuliano Cesarini (1466-1493-1510). Images: E. Puja, taken at the Palazzo Altemps museum. Below: at left, partial view of this monument used as a base for the Ludovisi Juno in the Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi ca. 1860; Bernini’s Pluto and Prosperpina (Schreiber 106a) is at right. Image: Grillet.

I also visited the Museo Nazionale Romano in Palazzo Altemps in Rome, keeping an eye out for ancient inscriptions from the Boncompagni Ludovisi collection that I did not yet have on my roster. For instance, I identified a modern Christian inscription, added in the late 15th or early 16th century to an ancient 1st century CE altar. The display label at the Museo Nazionale Romano explains that, by placing an urn and satyr torso on the altar, they replicate how these pieces were displayed in the private Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi in the 19th century. This is true, as it has been recorded that this same altar was once the base for a colossal head of Hera Ludovisi. Though modern inscriptions like this one are not included in my roster of ancient inscriptions, it is instructive for the family’s display strategies, as I will soon discuss.

Map of the Villa Ludovisi (from Schreiber 1880), showing relative position of constituent earlier villas and dates of acquisition by the Ludovisi or Boncompagni Ludovisi. The dividing line between the 17th century and 19th century acquisitions closely follows today’s Via Piemonte.

Inscriptions came to the Ludovisi in different ways. The villa of an 18th century antiquarian named Antonio Borioni (ca. 1690-after 1737), on the Pincio hill east of the Villa Ludovisi, also housed a large collection of inscriptions. And after being sold multiple times, it had become known as the Villa Paulsen by 1851, when the Ludovisi annexed the property, including all their inscriptions. And so, the other 30 inscriptions I have found were observed at the Villa Ludovisi-Paulsen.

Thanks to the CIL, we have much information on where these inscriptions were spotted before the Ludovisi owned them. Most have been lost, but I have managed to find the present location of several. Let’s take a look at some examples and see just how far these inscriptions have been scattered over the last couple of centuries.

Some inscriptions never left Ludovisi property. A few pieces thought to have been lost were found in the garden of the Casino dell’Aurora over the last decade and have been published as articles on our project website, villaludovisi.org.

The funerary monument (IGUR II 582) of Theodorus, son of Athenodotos, a Stoic philosopher and tutor of Fronto. Today it stands in the garden of the Casino dell’ Aurora. Images: T.C. Brennan; courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

One of these is a funerary monument in Greek (IGUR II 582) dedicated by Athenodotos, a philosopher admired by Marcus Aurelius, to his “hero” son, Theodoros, who died age 18 and received semi-divine honors.

Fragment of inscribed architrave from temple dedicated by P. Aelius Hieron to Hercules (AE 1907, 125), integrated ca. 1906 into garden fountain at the entrance of the Casino dell’ Aurora. Image: T.C. Brennan; courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Another inscription still on the property (AE 1907 125) was incorporated into a garden fountain, identified as the architrave or frieze of an imperial freedman’s temple dedicated to Hercules. He was the emperor Hadrian’s appointments secretary (ab admissione), as he proudly tells us in the inscription. But this inscription wasn’t recorded by Schreiber, as it was found in a family country estate in 1906 before being moved to Villa Ludovisi.

Images of funerary altar of Petronia Q.f. Rufina (Schreiber 134 = CIL VI 24047), today in garden of Casino dell’ Aurora, surmounted by vase. Images: T.C. Brennan; courtesy of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

The third and final inscription is on another altar in the garden: a funerary monument dedicated to Petronia Q.f. Rufina, which serves as the base for a large, unrelated vase. This altar must have been moved here from the Villa Paulsen since the Danish archaeologist Jørgen Zoëga (1755-1809) recorded its location there. In 1880, Theodor Schreiber then recorded the altar at the Villa Ludovisi. But not without noting that (rather than a vase) a Corinthian column capital was displayed on top, which means that it served as an interchangeable base for artwork.

This is the case for over a dozen inscribed altars, including that stacked modern inscription I mentioned earlier. In cases like these, the Ludovisi seem not to have valued the inscription itself. Rather, these inscribed altars were pieces in line with the theme, fitting the bill as something ancient that they could display other ancient pieces on top of.

Now, inscriptions that did leave Ludovisi property can be found near and far.

Relief (Schreiber 187) with inscription (CIL VI 640) to the rural god Silvanus, once embedded in an aedicula above the Great Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus, placed against the Aurelian Wall below the 3rd tower east of Porta Pinciana. Image at left: TC Brennan. Image at right: Prince Ignazio Boncompagni Ludovisi (1845-1913), taken in 1885.

One is a marble aedicule ornament, or relief sculpture that once decorated a small shrine. It was observed in one other house before Schreiber recorded it as being set into the pediment of a structure that sheltered the Great Ludovisi Battle sarcophagus, against the Aurelian Wall at the northern edge of the Villa Ludovisi. The ornament includes a bearded man with an animal at his feet, sculpted in relief. Along the top edge lies the faint inscription ‘Silvanus Custos’, marking it as a dedication to the rural god Silvanus, portrayed as a guardian on the shrine. Now, this inscription is in the Library of the American Academy in Rome, though how it got there is unknown.

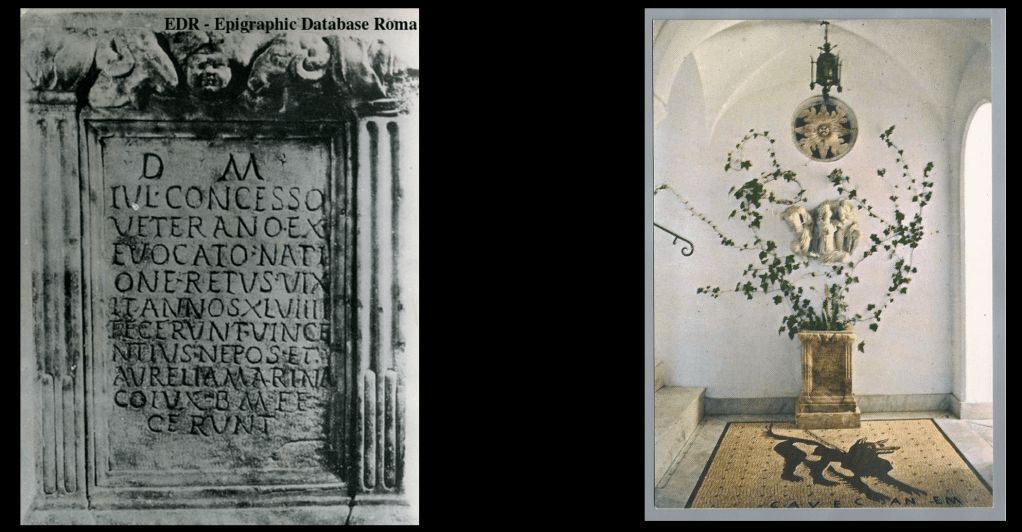

Image from Epigraphic Database Roma of CIL VI 3430 (funerary altar of the veteran Iulius Concessus), and postcard of the inscription in its present context at the Villa San Michele of Alex Munthe in Capri.

The next inscription is on a marble funerary altar, which was recorded at the Villa Paulsen. The altar memorializes a veteran named Julius Concessus, who was married to a certain Aurelia Marina and died at age 49. Above the inscription, the sculpture features a face with rams on either side. This inscription travelled a little further than the last, as it currently stands at the entrance to Villa San Michele on Capri, an island in the Gulf of Naples.

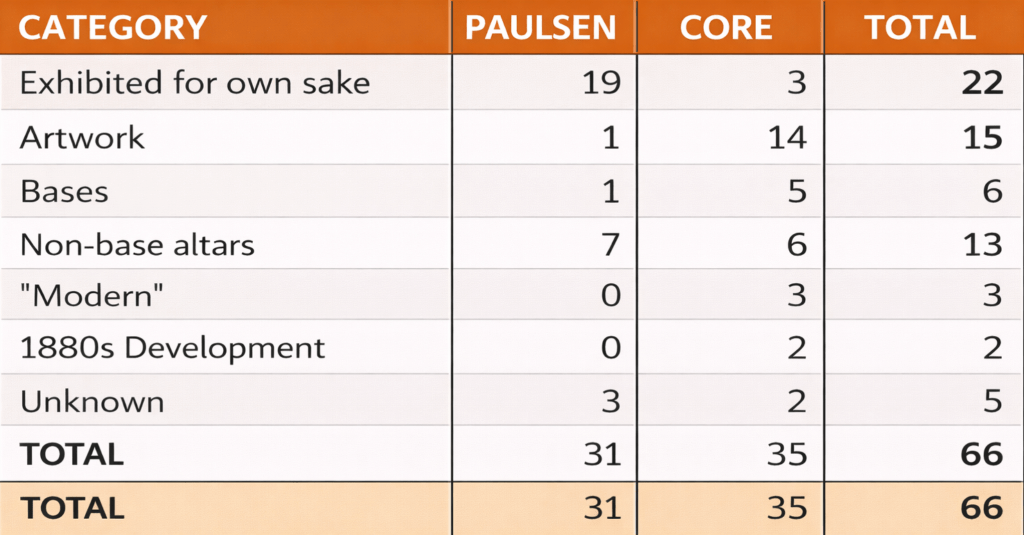

CIL VI 11264, funerary urn of C. Agrilius Iason, in collection of University of California, Berkeley. In the same collection is the ex-Ludovisi CIL VI 22438, the funerary altar of A. Messius Alexander.

So are there any inscriptions that made it out of Italy? Well, there’s a marble urn recorded at the gardens of the Villa Ludovisi that turned up at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at UC Berkeley. The head of the deceased Gaius Agrilius Iason, birds, and palmettes decorate the lid, while the relief sculpture on the urn itself features erotes (or winged cherubs) holding garlands below the inscription. Agrilius’s brother dedicated this inscription to “his patron and dearest brother.”

Those three ancient inscriptions are included on our roster of 61 inscriptions, for which I have categorized and compiled statistics.

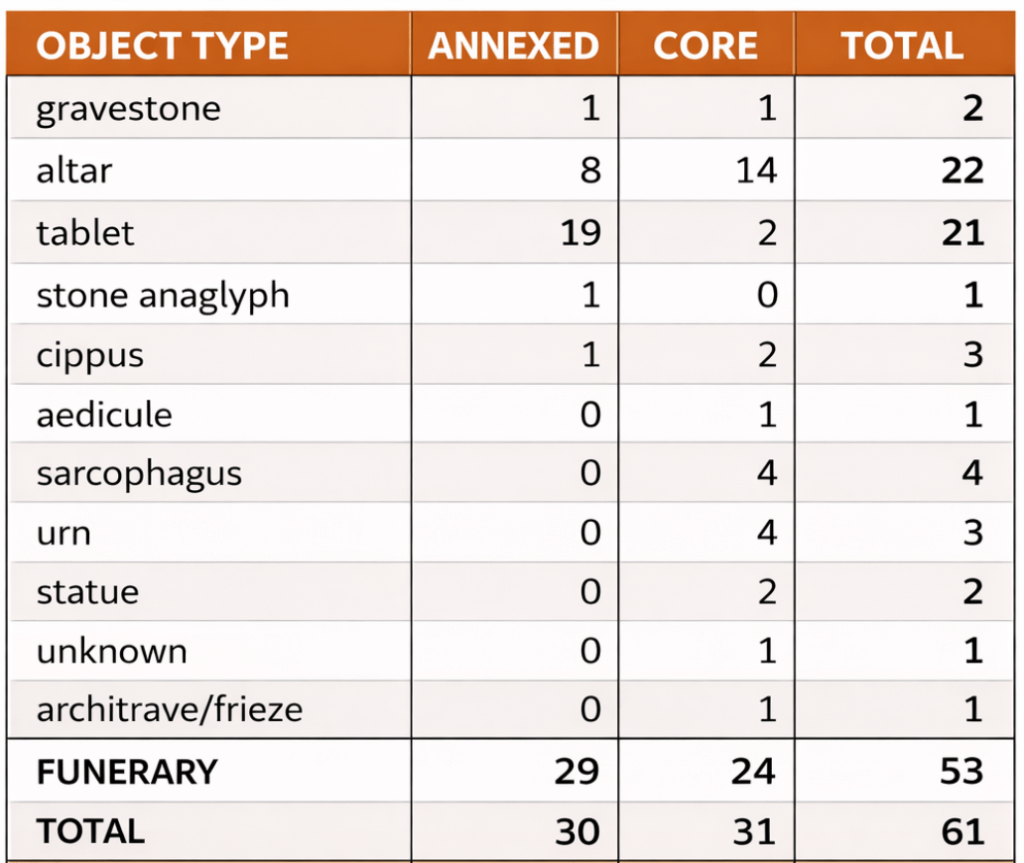

This table shows the breakdown of the inscriptions by object type, whether they are funerary objects, and whether they are from the core Ludovisi collection or annexed after 1851 from the Villa Paulsen. The number of inscriptions acquired consciously or through annexed property are nearly equal, at 31 acquired by the Ludovisi and 30 from the Villa Paulsen. Most are funerary because most surviving Roman inscriptions are funerary.

As for popular object types, altars and tablets come out on top. However, the Ludovisi collected most of the altars, and the Villa Paulsen collected the overwhelming majority of tablets. Little surprise there given our assumption that the Ludovisi were primarily concerned with artworks, rather than their inscriptions. To better confirm our assumption, I created a taxonomy for the inscriptions, so that we can categorize, quantify, and analyze Ludovisi collecting and display habits. (This taxonomy is not to be taken as an absolute categorization of what items should be considered artwork, rather a useful tool for understanding how the Ludovisi might have valued their inscriptions based on their display strategies.)

Epigraphy in both collections have been placed into the following categories: ancient inscriptions exhibited for their own sake, artworks that happen to have inscriptions, ancient inscriptions used as bases for artwork, altars with no record of being used as a base, “modern” inscriptions, items found in the late 1880s development of the Villa Ludovisi (which are not part of the Ludovisi collection strictly speaking), and unknowns.

Currently, we have images of only three out of seven altars not used as a base, so we cannot generalize them. However, those for which we do have images have little to no decoration compared to inscribed altars that did serve as bases.

From CIL VI 27772, text of ex-Ludovisi altar of Furia Sorana, now lost.

Here is a typical problem for my study. We do not have any images of the non-base sepulchral altar of Furia Sorana (which was moved to Villa Ludovisi from Villa Paulsen). If it is like the other non-base altars, it may have been another undecorated inscription exhibited for its own sake. However, the altar of Julius Concessus, which I talked about earlier, is a non-base altar from Villa Paulsen that does have relief sculpture. So we have no way of knowing whether the Ludovisi took the altar of Furia Sorana as art or for its own sake.

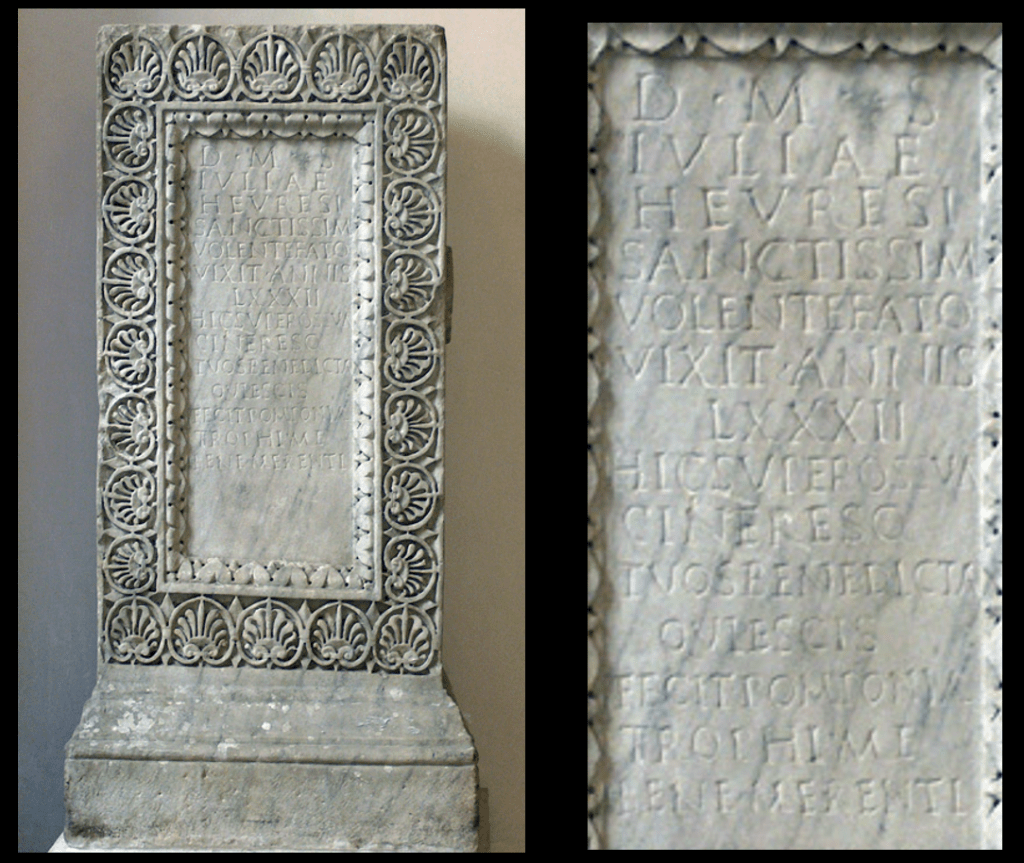

Above, from the Palazzo Altemps museum: CIL VI 20513, funerary monument of Iulia Heuresis, said to have died at age 82. Image: E. Puja. Below: image of this monument used as a base for the Giambologna Cesarini Venus in the Museo Boncompagni Ludovisi ca. 1860. Image: Grillet.

But perhaps those altars were valued for their own sake, while those used as bases—five, all with relief sculpture, and all recorded by Schreiber—were seen as better suited to be displayed with art. For example, the funerary altar of Iulia Heuresis is currently on display by itself at Palazzo Altemps in Rome, showcasing its border of palmettes in relief. It served as a base for two pieces of art in the Villa Ludovisi: a statue of a woman carrying a deer-like animal, and later a highly praised statue of Venus by Giambologna, today at the base of the main staircase of the US Embassy in Rome.

Above: large columned sarcophagus (Schreiber 212) with dextarum iunctio scene and poorly-carved inscription (CIL VI 28358 – 31593), commemorating Varia Octabiana (sic) and Aurelius Theodorus. Image: Clauss-Slaby. Below: 1806 sketch of sarcophagus with mismatched lid (Schreiber 213) by Louis-Hippolyte Lebas (1782-1867). Credit: L’École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts

Despite perhaps being better suited to be displayed with art, these bases were not necessarily appraised as works of art. Schreiber records a sarcophagus with an inscription in “careless letters,” and CIL says that same one has “very poor craftsmanship.” This sarcophagus served as the base for an unrelated sarcophagus lid with sculpture of a resting married couple. It may have been their best option for displaying the lid, putting it—and possibly the other bases—in a state of limbo between being valued as artwork or just happening to be on-theme for the art its supporting. As Hatice Köroglu Çam has shown on this website, the sarcophagus long protected the Ludovisi Pan but was relocated inside a protective enclosure around 1800, probably because of loose bricks falling from the nearby Aurelian Wall. Today, it can be found in Villa Ada, a park in north central Rome.

Some pieces in the roster can be categorized as artworks that just happen to have inscriptions. Relief sculpture decorates each of these pieces, but the types of objects that fall under this category vary. These total nearly half of the core collection.

Left: fragment of inscription CIL VI 36625. Image: Epigraphic Database Roma. Right: CIL VI 2283, sarcophagus fragment of P. Elius Petinus and P. Elius Florentinus, which Schreiber in 1880 found stored in the cattle-shed of the Villa Ludovisi. Image: Clauss / Slaby.

Just three inscriptions consciously acquired by the Ludovisi must have been valued for their own sake. These include two tablets and a fragment of the inscription on a sarcophagus. One tablet—last recorded at the Vatican Museum—features a funerary inscription described in CIL as having “very poor letters.” The other tablet fragment—last recorded at the (now closed) Museo della Civiltà Romana in Rome—includes not one full word. The only available image of the fragment from the sarcophagus of Publius Elius Petinus shows the full inscription mounted on a wall. As these examples have zero artwork, they exemplify epigraphy exhibited for its own sake.

This core collection contains 14 altars and just 2 tablets, in stark contrast to 19 tablets—out of 30 total inscriptions—from the Villa Paulsen collection. In fact, only three pieces displayed at Villa Ludovisi-Paulsen were remarkable enough to have been recorded by either Schreiber in 1880 or Palma in the 1980s.

Outside the Villa Ludovisi’s ‘Hermitage’, as seen in 1885, in photography campaign of Prince Ignazio Boncompagni Ludovisi (1845-1913). A monument to the praetorian guardsman Quintus Vetius Ingenuus (CIL VI 2514) is plainly visible at center, between vase and column and above sarcophagus. The monument stands today in the garden of the dell’ Aurora. Collection of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Here are my tentative conclusions on the display strategies of the Boncompagni Ludovisi. First, the Ludovisi seem to have collected inscriptions primarily for the artwork to which they are attached. Second, the Ludovisi show a clear preference for more grandiose objects. This applies to even the inscriptions we think were exhibited for their own sake—such as altars not used as bases. Finally, the fact that there are no famous ancient inscriptions from the Ludovisi despite the famous sculptures and paintings in their collection also speaks to their collecting habits and preferences.

Emilie Puja is a Master of Information student specializing in Archives and Preservation at Rutgers University, expected to graduate in January 2027. They presented their research about the Boncompagni Ludovisi collection of ancient inscriptions at the 2023 Annual Meeting of the Classical Association of Atlantic States and the 2025 Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America. Emilie would like to express their gratitude to Dr. T. Corey Brennan for his guidance and encouragement throughout their research, as well as HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for making her rich collection of inscriptions and archival materials accessible to study. They would also like to acknowledge Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss/Slaby (EDCS) for being instrumental in the discovery of inscriptions in CIL, as well as for some images of inscriptions uploaded to PABLO.

Leave a comment