An essay / translation in two parts by Michael Antosiewicz (Rutgers’18)

One of the most remarkable documents in the Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi at the Villa Aurora is the 22 December 1552 declaration written by Ugo Boncompagni, the future Pope Gregory XIII (1502-1572-1585), asserting the legitimate filiation of his son Giacomo Boncompagni, the Duke of Sora. That child had been born to him four and half years previous, on 8 May 1548.

This 1552 document represents the second of three efforts on the part of Ugo to secure the legitimacy of his son begotten out of wedlock. The first effort consists of a diploma of legitimation issued by Tommaso Campeggi, Bishop of Feltre (Veneto), on 5 July 1548, prefaced by a short declaration of paternity in Ugo’s hand, written on 20 July of that year. The third effort was a Papal Bull issued by Ugo as Gregory XIII on 13 June 1572, only a month after his ascension to the papacy.

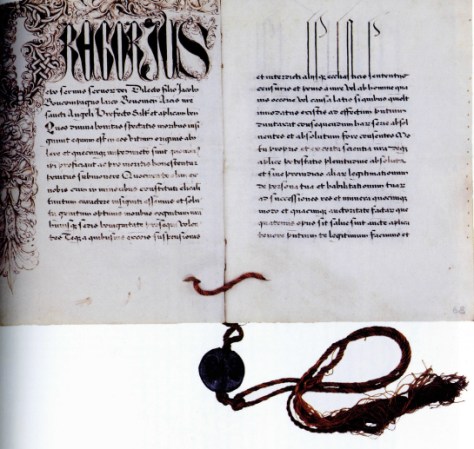

From July 1548, autograph declaration of paternity by Ugo Boncompagni (left) and legitimation document by Tommaso Campeggi, Bishop of Feltre, held in the Archivio Segreto Vaticano. Credit: G. Venditti et al., Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi. Inventario I (2008), plates facing p. 60

The December 1552 document is significant for a number of reasons. In the first place, it discloses full details of a story that would be unimaginable today: a Pope having a son. Secondly, it provides key insights into one of the most formative chapters of the Boncompagni (later Boncompagni Ludovisi) dynasty when the family’s destiny was in serious jeopardy nor foreseeable. Lastly, it captures a convergence of social, legal, cultural and ecclesiastical histories. You can see a transcription and translation of the 1552 Declaration in Part II of this post.

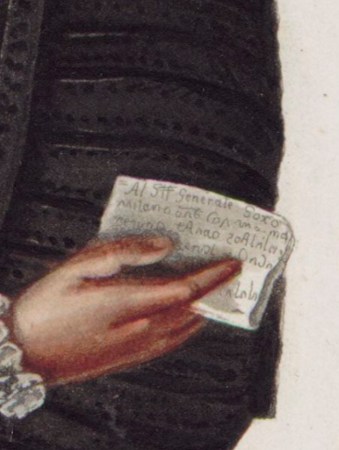

From Pompeo Litta, Famiglie celebri italiane II (1836). This image of Giacomo Boncompagni (detail) reproduces his (1594) portrait by Lavinia Fontana; that story is told here

Besides its scholarly significance, the document is also striking on account of its placement in the Boncompagni Ludovisi private archive over the past several centuries. To date, only a few scholars—and none in the last 60 years—have ever seen the declaration. For the circumstances of its preservation and rediscovery, and then second rediscovery, see here.

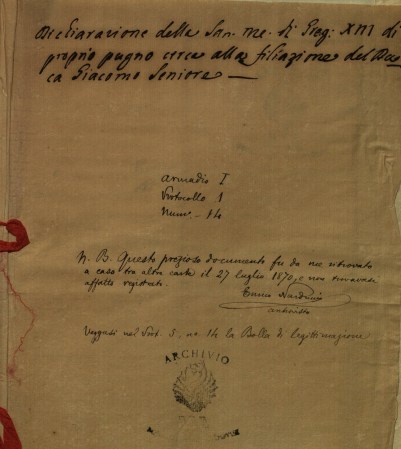

From the Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi at the Villa Aurora: archival “cover” for the 1552 declaration relating circumstances of its rediscovery in 1870

Boncompagni Ludovisi family archivist Giuseppe Felici typed up a tentative transcription of this document in the late 1940s, that has remained unpublished in the Villa Aurora archive. And Pio Pecchiai (1882-1965) in his article “La nascita’ di Giacomo Boncompagni” (Archivi 21 (1954) 9-47, at 32-34) published a transcription of this declaration, as well as those of additional documents that together form a dossier on the legitimation of Ugo Boncompagni’s son, with extensive commentary. But scholars have not had access to the document in the interim, and an English translation of the document has not existed before now.

However amazing and impactful this document is, it never should have been written. As a tonsured cleric on course to an austere life of legal and doctrinal disputes, Ugo Boncompagni was never supposed to have a son, if not for a family crisis compelling him for the sake of securing the family’s heredity.

Detail from diploma granting Roman citizenship to Giacomo Boncompagni, 27 July 1573. Collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Here is some basic background. Between 1543 and 1546, the Boncompagni family suffered a scourge of deaths. Altogether five of eight sons would perish: Gian Francesco (b. 1494), Antonio (b. 1496), Giorgio (b. 1498), Sebastiano (b. 1506), and Ludovico Boncompagni (b. 1507). These deaths had great ramifications for the process of inheritance; with the eldest son, Gian Francesco, dead, the inheritance had fallen into some confusion. This confusion peaked with the death of Cristoforo Boncompagni, the family’s patriarch, in 1546.

At the time of Cristoforo’s death, only three Boncompagni brothers were alive to manage their family’s estate, which now included a palazzo in Bologna still under construction. In addition to Ugo, there were his older brother by three years Girolamo Boncompagni (b. 1499) and his younger brother by two years Boncompagno Boncompagni (b. 1504). Unfortunately, neither Girolamo nor Boncompagno would prove viable heirs.

One would suspect that as the eldest remaining brother, Girolamo would have been a perfect heir, especially since he was already married, to one Laura Dal Ferro. The couple, however, did not have any children nor would produce any in their lifetime. If the family’s heredity was transferred to them, it would have soon been discontinued.

On the other hand, Boncompagno was an even worse candidate. Although he was married with a child, he was severely estranged from his family, especially from Ugo. Historians would later note that upon his election as Pontiff, Ugo refused to receive his brother at the Vatican. The exact reason for their estrangement remains uncertain, although his wife Cecilia Bargellini may have contributed to a rift between him and his father. Nonetheless, both Girolamo and Boncompagno did not represent viable heirs.

Detail from diploma granting Roman citizenship to Giacomo Boncompagni, 27 July 1573. Collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Ugo was as an equally unviable heir as his brothers if not more so. In 1539, he received the first tonsure and started his meteoric rise within the Church. This act barred Ugo from marriage and consequently eliminated any possibility of producing a naturally legitimate heir. Just as in the case of Girolamo, Ugo had no descendants to whom to transmit his family’s increasing heredity. In order for the Boncompagni family to retain their heredity, drastic measures had to be taken.

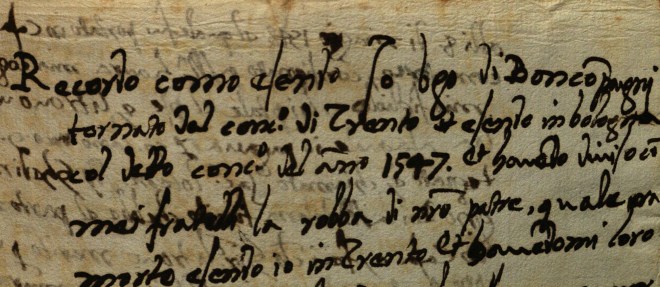

Having left the Bolognese universities in 1539 to work in the Roman Curia, in 1547 Ugo finally returned to Bologna, to attend the Council of Trent. In that year the Council was transferred from Trent to Bologna, though the Council was to never meet in this location.

Ugo had been aloof of the details of his family’s situation. In fact, the evidence suggests that Ugo did not know of his father’s death until he returned to Bologna. As one could imagine, his homecoming after an absence of eight years would have been hectic. He would have discovered not only the deaths of his father and his brothers, but the urgency of resolving the family’s inheritance crisis.

From the 1548 and 1552 documents we know the details of what happened next. When Ugo arrived in Bologna, Girolamo and his household inhabited the family’s new palazzo. One of the members of Girolamo’s household was an unmarried young woman (“dona soluta”) named Madalena De Fulchinis. She is described as staying with Laura, the wife of Girolamo, and most likely was a domestic servant. Ugo decided to have a child with her.

In the 1552 declaration, Ugo describes this sequence of events with the following (euphemistic) words: “hebbi da fare con lei e dopo alcuni giorni la ingravadai” (“I had things to get done with her, and after a few days I impregnated her”).

Over the next few months Madalena stayed in the family’s home. Right before she gave birth, Girolamo sent her to stay in the house of Maestro Alessandro, Ugo’s barber. On May 8, 1548 Madalena “made a masculine child” in Alessandro’s house; Giacomo was born!

Some time after she gave birth (no sooner than November 1548) Madalena was married to a Simone Antonio Scarani of Milan, a mason working in the palazzo. She went to live with Simone and had no part in raising Giacomo. Not much other information is available on the remainder of her life.

Giacomo was immediately delivered into the “guardianship” of his aunt Laura Dal Ferro, wife of Girolamo, and was raised by her. Ugo played no direct role in his upbringing at this time having immediately returned to Rome to resume Curial affairs. His only contribution consisted of his financial reimbursements to Laura and Girolamo for any costs incurred in raising the child.

According to the 1552 declaration, it seems Laura assumed this position without resisting. Moreover, Giacomo is said to have “resembled” those of the house, fitting into his home and his family’s elevated social sphere.

Detail from diploma granting Roman citizenship to Giacomo Boncompagni, 27 July 1573. Collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

With Giacomo’s birth, the process of legitimation commenced to make Giacomo a legal and rightful heir. Back in Rome Ugo stayed at the house of Tommaso Campeggi, the Bishop of Feltre, who himself hailed from a prominent Bolognese family. Just two months after his birth, on 5 July 1548, Campeggi issued a diploma that legitimated Giacomo. In his own handwriting, Ugo a few weeks later (on 20 July) added a paragraph to the front of the document that briefly summarizes the circumstances of conception and the sequence of events.

Although Ugo technically accomplished his goal of securing a legitimate heir, he continued to reaffirm Giacomo’s legitimation. The 1552 document plays a special role in this process.

Whereas the 1548 diploma and the 1572 document wield ecclesiastical authority, the 1552 declaration constructs a legal argument for legitimation. The declaration operates in two parts and uses two languages.

Detail from diploma granting Roman citizenship to Giacomo Boncompagni, 27 July 1573; he had been prefect of the Papal stronghold of Castel S Angelo (depicted here) since 23 May 1572. Collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

The first section cites, in Latin, legal precedents for legitimation. The legal precedents derive from the Consilia of Pietro Paulo Parisio, Ugo’s prolific colleague at the University of Bologna.

The next section, in Italian, demonstrates compliance to the legal stipulations. The Italian narrative relates the sequence of events once Ugo returned to Bologna, the circumstances of conception, the arrangement of Madalena’s marriage and dowry, as well as the arrangements for Giacomo’s upbringing.

Most importantly, the document provides an extensive and comprehensive list of all those in the house or close to the family’s affairs that possessed knowledge of the affairs and thus could corroborate claims of legitimation. In fact, out of the document’s total four pages, nearly one full page of witnesses is given by Ugo—ranging from the family’s many friends, to workers in the house, to the tenant farmers on the Boncompagni estate.

Detail from diploma granting Roman citizenship to Giacomo Boncompagni, 27 July 1573. Collection of HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

A close reading of the document provides details and insights into Ugo’s mindset and reasons for producing the 1552 declaration.

First and foremost, Ugo clearly wanted to ensure that Giacomo’s reputation and legitimate filiation were unassailable. He states: “cusi lo te(n)go p. tale mio figlio e, da tutti voglio sia tenuto e, cognoscuto Ne credo che alcuno li possa dir(e) el contrario se no(n) p. malignita” (“As such I hold him as my son, and from everyone I want him to be acknowledged and held; nor do I believe anyone could speak the contrary against him if not for malignity”).

Furthermore, it is clear that Ugo decided to have a child out of familial necessity. With chilling ease he explains in the beginning of the document that he decided to “provide myself with children” who “potesano habitar in deta casa volendo io stare a roma” (“could live in the said house [the Palazzo Boncompagni] since I want to stay in Rome”).

Clearly, Ugo wished to continue his ascendance in the Curia and viewed Giacomo as a way to secure and maintain a presence over the family’s affairs in Bologna.

Another interesting facet of the document consists of its legal language. Ugo uses particular words and phrases throughout the document as well as emphasizes certain details.

One legal formulation stands out; it concerns the family’s public reputation: “p. eser l’intentione mia di maritarla azo no(n) si palegiase cusi che havese fato uno figliolo anchora che si dicesse publicame(n)te chera gravida di me” (“it being my intention to marry her off, she [Madalena] therefore did not show herself in a way that she had a child, although she did publicly declare to be pregnant by me”).

For the sake of legitimation Ugo’s paternity had to be well-attested, but knowledge of Madalena’s giving birth could not be dispersed publicly as it would interfere with her marriage to Simone the mason.

The legitimation process of Giacomo Boncompagni finally ends 24 years after his birth, and 20 years after our document. In a Papal Bull of 1572, Ugo decrees his son’s legitimate filiation and thus also validated his social prominence.

From 1572, Papal bull by Pope Gregory XIII legitimating his son Giacomo Boncompagni, held in the Archivio Segreto Vaticano. Credit: G. Venditti et al., Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi. Inventario I (2008), plates facing p. 60

On the whole, this series of events concerning the legitimation of Giacomo Boncompagni constitute more than one of the most crucial periods in the history of the Boncompagni Ludovisi dynasty. It details and illuminates a world that in so many ways feels so remote but yet reverberates to the present day.

A transcription and translation of the 1552 Declaration follow in Part II of this post.

Warmest thanks, as always, are owed to HSH Prince Nicolò Boncompagni Ludovisi and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, for making this archival research possible.

From Pompeo Litta, Famiglie celebri italiane II (1836). This image of Giacomo Boncompagni (detail) reproduces his (1594) portrait by Lavinia Fontana; the letter shows his status on the “Secret Council” of the Duchy of Milan

[…] as student contributions to the project website villaludovisi.org show. For instance, one find, published by Michael Antosiewicz ‘18, has been an autograph declaration from 1552 of the future Pope Gregory XIII, attesting to the […]